Scientists discover world's oldest clam, killing it in the process

Loading...

A team of researchers has reported that Ming the Mollusk, the oldest clam ever found, is in fact 507-years-old, 102 years older than the previous estimate of its age. But that is as old as Ming will ever get.

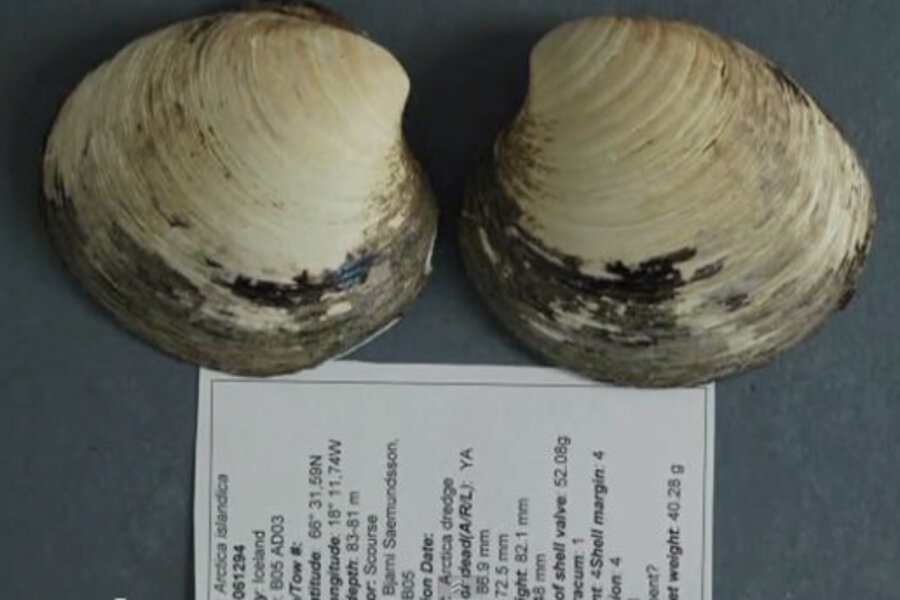

Ming, an ocean quahog clam, was pulled up from 262-feet-deep waters off the coast of Iceland in 2006. Scientists from Bangor University, in the United Kingdom, who were studying the long-living clams as palimpsests of climate change, analyzed the lines on its shell to estimate its age, much as alternating bands of light and dark in a fish’s ear-bones are used to tell how old the animal is. This clam was 402 years old, the team said. It was called Ming, after the 1368-to-1644 Chinese dynasty during which it was born.

But a new analysis of the clam has put the hoary mollusk at 507-years-old, which means that it was born in 1499. This is the same year that the English hanged a Flemish man, Perkin Warbeck, for (doing a bad job of) pretending to be the lost son of King Edward IV and the heir to the British throne. It’s also the same year that Switzerland became its own state, the French King Louis XII got married, and Diane de Poitiers, future mistress to another French king, Henry II, was born.

When it was first found in 2006, Ming, celebrated as a disinterested non-observer to centuries of world upheavals, a hermetic parable of the benefits of not interacting at all with humans, with whom the clam is unlucky enough to share the planet, was called the world’s oldest animal. But, after some quibbling about whether that distinction should go to some venerable corals, the distinction was downgraded to “world’s oldest non-colonial animal,” because clams don’t grow in colonies as corals do. The Guinness Book of World Records simplifies the grandness of it all and just calls Ming the world’s oldest mollusk.

But this is a record that other clams are well placed to beat. That’s because Ming is not getting older. To study Ming’s senescent insides in 2006, the researchers had to pop the clam open. Ming died. It's Wikipedia page reads in the past tense.

Following a fair bit of outrage about how badly Ming’s first contact with humans had panned out, the team pointed out to the BBC that ocean quahog clams are used in clam chowder all the time and that these soup clams might also be hundreds of years old. None of the other 200 clams dredged up in their climate change research got names, they also said.

Ocean quahog clams are well known to live to be very, very old, but it’s not certain why that is. Like other long-lived animals, such as the naked mole rat, the animal has been a subject of much research, in hopes of applying their long-life secrets to humans.

The previous Guinness record-holder for oldest clam, before the upstager Ming came along, was a 220-year-old ocean quahog clam pulled from American waters in 1982. A 374-year-old clam, collected in 1968, is also displayed in a German museum, National Geographic reported.