Were most cave painters women? Their hand prints say yes.

Loading...

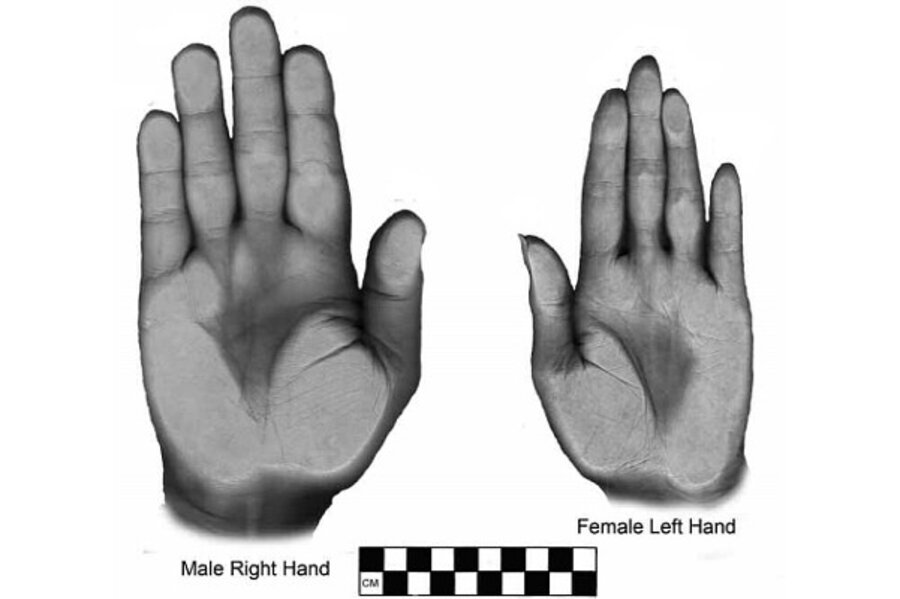

Look at your hands. Is your ring finger longer than your index finger? And is your pinkie finger almost as long as your ring finger? If you answered yes to both questions, you're probably a man. (That or you're a woman with "man hands.")

The role of finger ratios to sex has been known for years, but a new study has taken that conclusion and pushed it in an unexpected direction: underground. Specifically, into caves that were painted about 30,000 years ago.

Ancient humans made hand prints or hand stencils on every inhabited continent in the world, but these cave paintings have always been attributed to men, because they're often associated with paintings of the creatures that early humans hunted, and probably for other reasons related to latent sexism. Smaller hands were attributed to young men or boys.

"When I first became aware of the digit ratio measure, by reading John Manning's book," says Dean Snow, an emeritus anthropology professor at Pennsylvania State University, "I walked over to the shelf and pulled off a book that's been sitting there for 40 years. I opened the flyleaf and there was a hand stencil from the cave at Pech-Merle, which I ended up using in my work. If John were anywhere near right, that was a woman's hand. It was not masculine at all. And so I thought, 'Wow, there were women down there! At least one. I wonder how many more there were?'"

Because physical traits differ with geography, Dr. Snow limited his study to caves in northern Europe. He also gathered hand measurements from over a hundred students of northern-European ethnicity, to create a modern benchmark. He found that hands fall along a continuum, from very dainty, feminine hands to very masculine hands, with a big grey area in between. He eventually developed a two-step process to predict sex just based on hand prints.

First, measure the lengths of the fingers and palm, and put the numbers into a formula Snow developed. That sorted modern hands into male and female with about 80 percent accuracy. But adolescent males, whose hands haven't reached full size, too often got lumped in with women, so Snow added a second step: look at the ratios between the fingers.

For women, the index and ring finger are often the same length, though occasionally the pointer is longer. For men, the ring finger is often noticeably longer. Then compare the pinkie to the others. In most males, young or old, the pinkie is nearly as long as the ring finger, extending up past the ring finger's highest knuckle. In women, the pinkie can be a good inch or so shorter than the ring finger.

The second step alone could distinguish young men from women with 60 percent accuracy, which Snow acknowledges is more ambiguous than he'd like. But then he found something even more surprising: the overlap between male and female hands is a modern problem.

Back in the Upper Paleolithic, physical differences between males and females – what scientists call "sexual dimorphism" – was more pronounced than it is today.

"If you scale all hands in a modern sample on a single scale, they scale from very, very feminine to very, very, masculine, and there's a great deal of overlap in the middle," Snow explains, "but when I plotted the cases from the caves against the modern distribution of several hundred individuals, the cave specimens all came out at the very ends – and in some cases beyond the ends – of the modern range of differences between males and females."

Snow visited 11 cave regions across France and Spain, focusing on caves famous for their numerous hand stencils. Unfortunately for anthropologists, blowing paint around a hand doesn't always leave a precise print of the hand, plus thirty or forty thousand years of erosion have damaged most of the samples. Of the hundreds of hand prints he examined, Snow was able to take precise, reproducible measurements of just 32, including five from Pech-Merle, the site whose photograph had launched his study.

"Now, 32 doesn't sound like a very big sample," Snow acknowledges, "but it's actually pretty big compared to the sample sizes archaeologists are often dealing with." Plus, traveling around Europe isn't always cheap: "It was as many as I could get with the amount of funding I had."

So what did he find? Only 10 percent of the hand prints on cave walls in Spain and France were left by men, and another 15 percent came from adolescent males. Fully 75 percent of the hand prints on cave walls were female.

Traditional explanations for the hand prints have focused on hunting or perhaps shamanism, but the prevalence of women's hands has reopened the question of what they mean. One researcher has suggested that these could relate to midwifery or fertility, either of humans or the animals drawn on the cave walls. But it could be that women were more involved in hunting and religious rituals than previously thought.

Snow is less captivated by the "interesting but still speculative ideas about what it might all mean," instead focusing on the groundbreaking recent discovery that cave paintings can be given surprisingly precise ages.

"Are these hand stencils the same age as the animals they surround, or not? Are all the hand stencils from one part of the upper Paleolithic, or are they distributed across the whole time range? We don't know – yet."