Spitzer telescope revolutionized how we see the universe

Loading...

Ten years ago, on an August afternoon in Florida, a Delta II rocket was launched skyward. Atop that rocket was the Spitzer Space Telescope, named for the theoretical physicist Lyman Spitzer, who had in 1946 proposed that, just maybe, a telescope could operate in space.

The Spitzer Space Telescope is the fourth of NASA’ Great Observatories, a group of telescopes that offers images of the universe in different wavelengths of light: Hubble, Compton (no longer active), Chandra, and Spitzer. Spitzer, which celebrates a decade of photographs today, sees the cosmos in infrared.

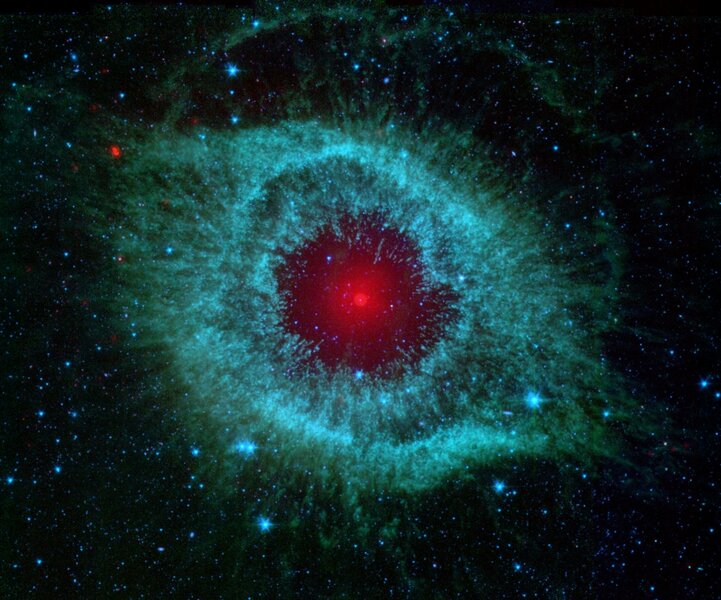

In these last ten years, Spitzer has seen a lot: a star flung out of its solar system in another star’s explosion, streaking the sky with a pink shockwave, like a runaway bride’s peony-colored veil flapping down the aisle; star nurseries pictured in reds and greens, akin to celestial kingdoms lit up to celebrate the birth of a prince there, a princess here; a nebula that resembles a giant eye rimmed in blue glitter eyeshadow.

These Spitzer murals, as well as those from its three sister telescopes, have helped shape how we see the universe. Now, space appears like a small corner of a Monet painting magnified into a landscape brimming with light.

Of course, Spitzer has provided more than art. Spitzer's photos have told us that there is such a thing in the universe as a bucky-ball (or, Buckminsterfullerene), a carbon molecule shaped like a soccer-ball. Its photos have shown us an additional sparse ring of ice and dust rimming Saturn and revised the shape of our galaxy as we know it.

And Spitzer, the first to detect light coming from a planet outside our solar system, has also revealed the unusual atmospheres cradling other worlds spinning around other stars. It has plumbed the depths of space for the shape of other galaxies, finding that those systems of countless stars and planets are more massive than ever before thought.

In 2009, Spitzer ran out of liquid helium to cool its cameras to the lows needed to be fully operational. But there's still some scientific life here: The two shortest-wavelength modules in the Infrared Array Camera remain functional.

Now, scientists are using Spitzer to find an asteroid to lasso. In October, Spitzer will make infrared observations of a near-Earth asteroid called 2009 DB. That asteroid could become the target for the agency’s Asteroid Redirect Initiative, an ambitious scheme to bundle one up and then send humans to sample it.