Fallout from the Russian fireball encircled Earth, research shows

Loading...

Six months ago, Russians watched a massive fireball streak across the sky. The sperm-whale-sized asteroid exploded before it hit the ground, shaking the air and land with as much force as a 440-kiloton nuclear bomb and shattering into countless rocks, shards, grains, and dust-sized particles.

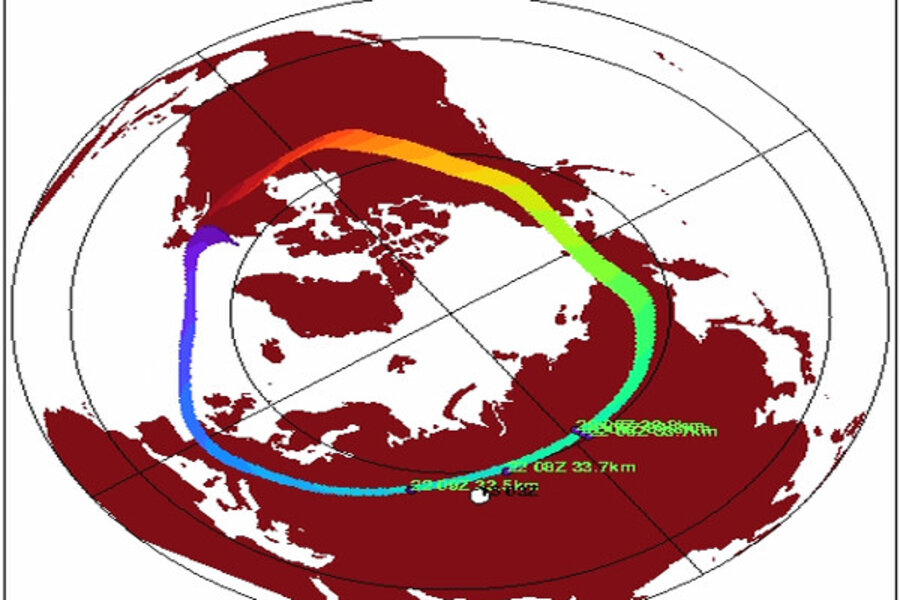

The heaviest of these quickly fell to the ground, leaving a 60-mile-long swath of debris that fell along the meteor's trajectory. But the smaller and lighter fragments rose up, mushroom-cloud style, till they were caught by high-altitude winds that carried them around the world. According to a paper recently accepted by Geophysical Research Letters, microscopic meteorite grains were blown first across the Russian skies, then across the Pacific to Alaska and Canada, then over the Atlantic, ultimately encircling the globe with a ring of space debris.

"After the meteor exploded, like a fireball from a nuclear explosion, the material lifted very high," says Paul Newman, an atmospheric physicist with NASA. "And then the winds – what we call the Polar-Night Jet – carried that material around the northern hemisphere very quickly, forming this belt of particles." It reached Alaska by the next day, and looped the planet within four days.

What goes up ... doesn't always come down?

It's not unusual for fine material to stay aloft. "Imagine you took a handful of flour and threw it across the room. The bigger particles in flour will fall out quickly, and the smaller particles will continue to float in the air," says Dr. Newman, who is the chief scientist for atmospheric sciences at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. (See "Play along at home," below.)

The particles from the Chelyabinsk blast, he says, are almost unimaginably small. "When the meteor exploded, it really pulverized the entire meteor," says Newman. "Literally, these particles were a thousand times smaller than the width of a human hair." And because they're so incredibly small, he explains, "they settle at a very, very, very slow rate."

The biggest of these microfine particles fell a few hundred feet per day, estimates Nick Gorkavyi, the lead scientist in the team, while the smallest fall less than 15 feet per day.

Within hours, NASA's Ozone Mapping Profile Suite had spotted the plume – "over Siberia, a thousand miles from Chelyabinsk," says Dr. Gorkavyi, a programmer with NASA contractor Science Systems and Applications, Inc. "We were surprised: Why so far?" The initial atmospheric models had predicted a much slower spread across the sky.

"Nick and Didier [Rault, another co-author] came to me and said, 'Something's wrong with the model,' " says Newman, who had designed the atmospheric model. "I said, 'Let me look at it." He went back to Gorkavyi and Dr. Rault and said, " 'It had to be at a higher altitude.' And then Nick and Didier came back and said, 'Oh, yeah, well, we know from all the photographs and all the video from the ground that the plume quickly rose up like a mushroom cloud, rose up, rose up, to 35 kilometers.' And I said, 'Well, that's the answer: That's why it drove around so fast. The winds at higher altitude are a lot faster than winds at lower altitude."

The "mushroom cloud" had lofted the particles into the Polar-Night Jet, the winter season (hence "polar night") high-altitude stream of air that whizzes from west to east at "a couple hundred miles per hour," says Newman. But the Polar-Night Jet is thousands of feet higher than the initial explosion, which is why he hadn't taken it into account in the initial modeling.

That's how the dust layer managed to surround the entire planet, Newman says. The high-altitude winds "lapped" the low-altitude winds. "That's where you get the snake-uncoiling effect, where the head of the snake catches up with the tail," Newman says, describing the image above. "Because at higher altitudes, winds are faster."

Play along at home

You can create your own model of micro-fine atmospheric dispersal. All you need is a bag of flour and a smooth surface. A table or hardwood floor would work, but we strongly recommend a driveway or sidewalk to minimize cleanup and/or getting in trouble. Reach into the bag and take out a big handful of flour. Throw it like a baseball and watch what happens.

You'll first notice how much of the flour doesn't fall at all, but just hangs in the air, getting tossed around by any passing breeze. Some will actually blow upwards, in defiance of gravity, if caught by a puff of air. (When I tried it, I thought the air was perfectly still, but the tiniest of breezes was still enough to throw around the cloud of flour dust I'd created.) Once all the airborne flour has blown away or clung to a nearby surface (tree, car, clothes), look down at the ground and see how much of the initial handful of flour did fall, while you were distracted by the airborne cloud. You'll see hundreds of tiny little white impacts spreading out along the direction of your intended trajectory, just like the thousands or millions of meteorite fragments that spread along 60 miles of the ground near Chelyabinsk.

When it entered Earth's atmosphere at about 42,000 miles per hour, the meteor measured 60 feet in diameter and weighed about 12,000 tons. It exploded near Chelyabinsk on February 15, 2013 at 9:20 a.m. local time, with an energy release equivalent to more than 30 Hiroshima atomic weapons. The blast shattered windows across the region, including some in Gorkavyi's parents' home.

"In Chelyabinsk, this is event of century," says Gorkavyi.

He missed seeing it live in his hometown, "but I catch it from the other side," he said, "from space."