In planet-hunting, "Earth-size" has been a relative term. Given that larger planets are easier to detect, anything in the "Earth-size" ballpark has been celebrated. With the discovery of Kepler-20e and 20f, however, scientists bagged their first actual Earth-size planet-candidates.

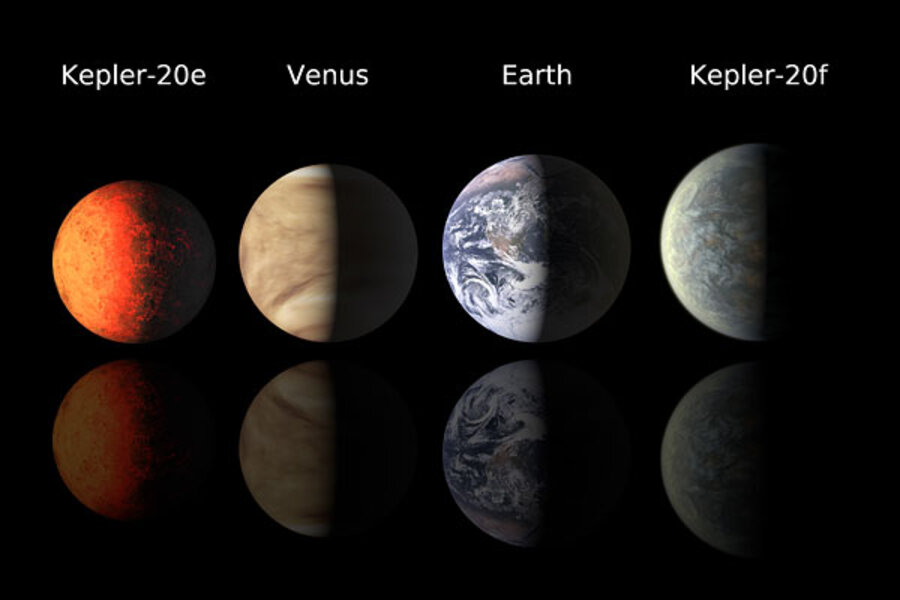

In fact, in Kepler-20e, they for the first time found an exoplanet smaller than Earth – 0.87 times its size, to be exact. And at 1.03 times Earth's size, Kepler-20f is almost a precise match.

Both are thought to be rocky, though neither is thought to have an atmosphere, as both are closer to their star than Mercury is to the sun. Kepler 20e orbits at a distance of 4.7 million miles, completing a revolution every 6.1 days. Kepler 20f orbits at 10.3 million miles, taking 19.6 days to complete one circuit. Mercury orbits our sun at a distance of 35 million miles and its year lasts 88 Earth days.

Like the Kepler-11 system, the Kepler-20 system also challenges current models of solar-system formation. Particularly puzzling is the fact that three larger, Neptune-size gas planets are interspersed among the two rocky planets in an alternating order: gas / rocky (20e) / gas / rocky (20f) / gas.

"The architecture of that solar system is crazy," science team member David Charbonneau of Harvard University said during a teleconference announcing the finding in December 2011. "This is the first time that we've seen anything like this."