Prehistoric warming linked to CO2

Loading...

Rising carbon dioxide levels may have caused Antarctic warming in the past, new research strongly suggests.

The findings, published today (Feb. 28) in the journal Science, just add to the body of evidence that human-caused greenhouse gas emissions will lead to climate change.

"It's new evidence from the past of the strong role of CO2 [carbon dioxide] in climate variation," said study co-author Frédéric Parrenin, a climate scientist at the CNRS in France.

Past data

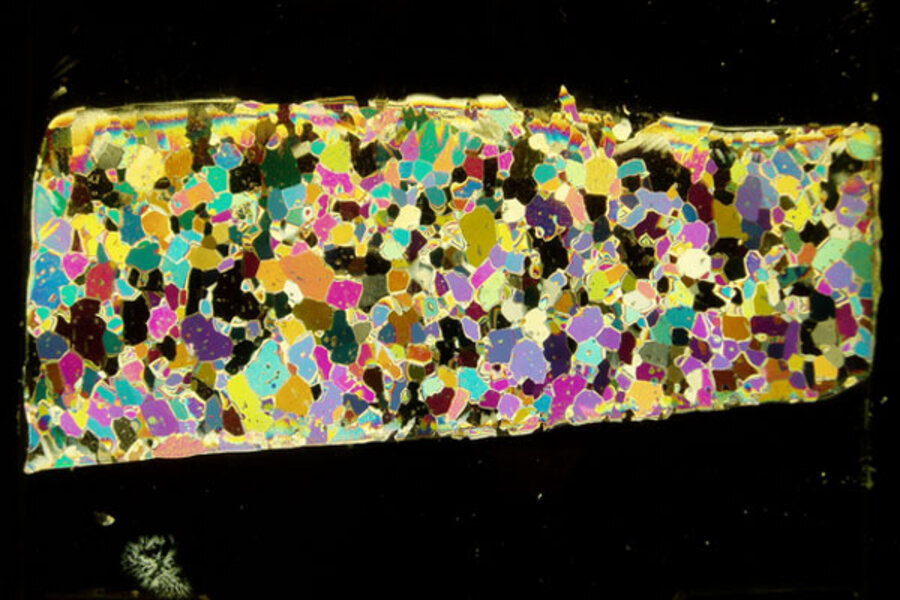

Eons of the Earth's climate history are revealed deep within ice sheets in the Arctic and Antarctic. The Antarctic ice traps gas bubbles from the climate that can reveal what the ancient atmosphere looked like, while the ice itself can reveal historical temperatures.

But gas bubbles from a given period get buried deeper than ice of the same period, making it hard to tie past temperatures with atmospheric changes.

In the past, scientists using older techniques found that increases in carbon dioxide happened after global warming, not the reverse. [Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice]

Past link

But Parrenin and his colleagues wondered whether that was actually the case. To answer that question, the team looked at five ice cores that had been drilled from Antarctica over the last 30 years.

They focused on ice from 20,000 to 10,000 years ago, which encompassed the last period when the planet warmed naturally and glaciers melted.

The team measured the concentration of nitrogen-15 isotopes, or atoms of the same element with different weights, at different depths throughout the ice cores. They compared the depth of that isotope with the ice composition for all the cores to determine the distance between ice bubbles and ice from the same period.

Global warming

The team found that global warming and a carbon dioxide increase happened at virtually the same time — between 18,000 and 11,000 years ago.

"It makes it possible that CO2 was the cause — at least partly — of the temperature increase during the courses of the last glaciation," Parrenin told LiveScience.

And if increased carbon dioxide could lead to rising temperatures in the past, it also can in the present day, he said.

The findings may deflate some climate skeptics, who used the poor dating of ice cores to question the link between carbon dioxide and warming, said Robert Mulvaney, a glaciologist with the British Antarctic Survey, who was not involved in the study.

It also confirmed the view of most climate scientists that in the past, rising temperatures and carbon dioxide were locked in a feedback loop, where high temperatures led to more carbon dioxide being released from the deep oceans, which increased temperatures further, Mulvaney said.

But because predictions of future warming are based on recent carbon dioxide and temperature data, not historical models, "it hasn't really changed anything about our understanding of how climate change will change our modern environment." Mulvaney told LiveScience.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter @tiaghose or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

- Image Gallery: One-of-a-Kind Places on Earth

- The Reality of Climate Change: 10 Myths Busted

- 8 Ways Global Warming Is Already Changing the World

Copyright 2013 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.