Millionaire plans to send couple to Mars in 2018. Is that realistic?

Loading...

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy charged NASA with putting humans on the moon within the decade. Now, the world's first space tourist, multimillionaire Dennis Tito, formally unveiled plans to send two humans to Mars and back on a nonstop, 501-day mission, with the launch envisioned for January 2018.

The audacious project, which Mr. Tito is bankrolling out-of-pocket for the first two years, is driven by a mixture of motives: part America first, part research, and an enormous dash of what he and his partners hope will be inspiration to a nation whose government space program is caught between tight budgets and an unclear direction for its human spaceflight effort.

NASA's current plans don't call for a human mission to Mars for more than a decade.

The Mars flyby mission announcement came Wednesday, shortly after the House Subcommittee on Space held hearings on the Space Leadership Preservation Act, a bill that would overhaul the way NASA is funded and how its leadership is structured.

During the hearing, Rep. Chris Stewart (R) of Utah spoke of goals for NASA and said, "It will be disappointing to some of us if Google goes to Mars before the government."

In this case, however, it's not Internet titan Google spearheading the mission, but the Inspiration Mars Foundation, a nonprofit group Tito and others established to execute the project.

A team from the foundation is presenting the results of a mission-feasibility study next weekend at an Institute of Electronics and Electrical Engineering (IEEE) aerospace conference in Big Sky, Mont.

"All of the work done to date show the mission is possible, just barely," said Taber MacCallum, CEO and chief technology officer for Paragon Space Development Corporation and the Inspiration Mars Foundation's chief technology officer, during a press conference in Washington on Wednesday.

At the same time, however, the study also shows that it will take the Orion capsule and the space-launch system NASA is working on to pull off a mission to explore Mars with a crew of scientists, he said.

The Inspiration Mars mission is an austere one whose schedule is dictated by a very favorable alignment between Earth and Mars in 2018. The alignment allows a simple round trip to take 501 days, and the alignment won't appear again until 2031.

The two-member crew, a man and a woman, would launch Jan. 5, 2018, take one swing around Mars, coming to within 100 miles of the surface on Aug. 21, then return to Earth in an approach and reentry no one has tried before, landing on May 21, 2019.

In a version of the feasibility study papered for the IEEE presentation next Sunday, Tito and colleagues from three aerospace companies, NASA's Ames Research Center, and Baylor University's Center for Space Medicine in Houston envision a Spartan craft where sponge baths replace showers and the crew will recycle water and oxygen with technologies similar to those used on the International Space Station.

Simplicity is vital to keep the craft's mass to levels a large rocket can readily loft from Earth, explained Mr. MacCallum of Paragon Space Development Corporation, which specializes in environmental controls and life-support systems for spacecraft.

The craft will have no propulsion system of its own but will rely on the push it gets from the final stage of its rocket and gravitational assists to get to Mars and back. Like a submarine, the craft is being designed so that all systems can be serviced from inside, eliminating the need for systems to support spacewalks and bulky space suits.

The mission envisions using a rocket with capabilities similar to those of the Falcon Heavy rocket, developed by the Space Exploration Technologies Corporation. Scheduled for its first demonstration flight later this year, the Falcon Heavy would be the most powerful rocket since NASA's Saturn V, which launched astronauts to the moon during the Apollo program.

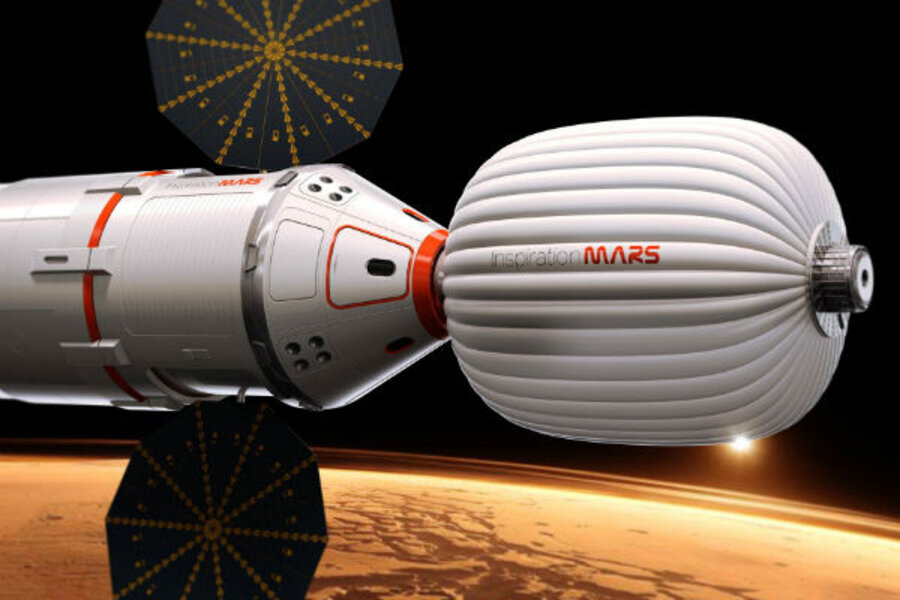

Fully loaded, the Inspiration Mars capsule would tip the scales at about 10 tons, so it could be lofted by either the Delta IV or Atlas V, well-established workhorses for launching large satellites and robotic exploration missions. The capsule would host about 600 cubic feet of living space and 600 cubic feet of cargo space. The capsule could include an inflatable module to expand living space, foundation representatives said, although that would add complexity to the craft.

"There really are multiple options for basically every function we need" to pull off the mission, said MacCallum.

Already the foundation has signed a Space Act agreement with the NASA Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, Calif., to tap its expertise on heat shields and reentry approaches.

Still, the challenges are enormous. The schedule is tight, and the funding after the first two years – the least-expensive years, Tito acknowledges – is uncertain. And the risk to the mission's crew, likely a middle-aged married couple, is considerable.

From a physical standpoint, the biggest risk the crew is likely to face comes from the radiation hazards of interplanetary space – from galactic cosmic rays and from intense bursts of particles from the sun during powerful solar storms. The radiation exposure the crew would experience during the Mars mission exceeds the amount of exposure that NASA allows its astronauts to undergo, said Jonathan Clark, a former NASA flight surgeon and an associate professor at Baylor's Center for Space Medicine.

And while this mission's radiation-hazard standard is not as stringent as NASA's, Dr. Clark said, "don't believe that we are looking at this lightly; this is a super concern."

Of particular concern are any acute effects from radiation that might impair a crew member during the mission.

In addition, the team is focusing on ways to offset, through preflight training as well as in-flight activities, the effects of prolonged weightlessness and on the psychological effects of long periods spent in confined spaces.

"The real issue here is understanding the risk in an informed capacity – the crew would understand that, the team supporting them would understand that," Clark said.

The mission won't come cheap, although Tito said it's too early to put an overall price tag to the project. His best guess would be less than what the US spends to send robotic missions to Mars.

"This is really chump change compared to what we've heard before" on estimates for landing a crew on Mars, he said.