Asteroid mining: Second company announces plans. Time to stake a claim?

Loading...

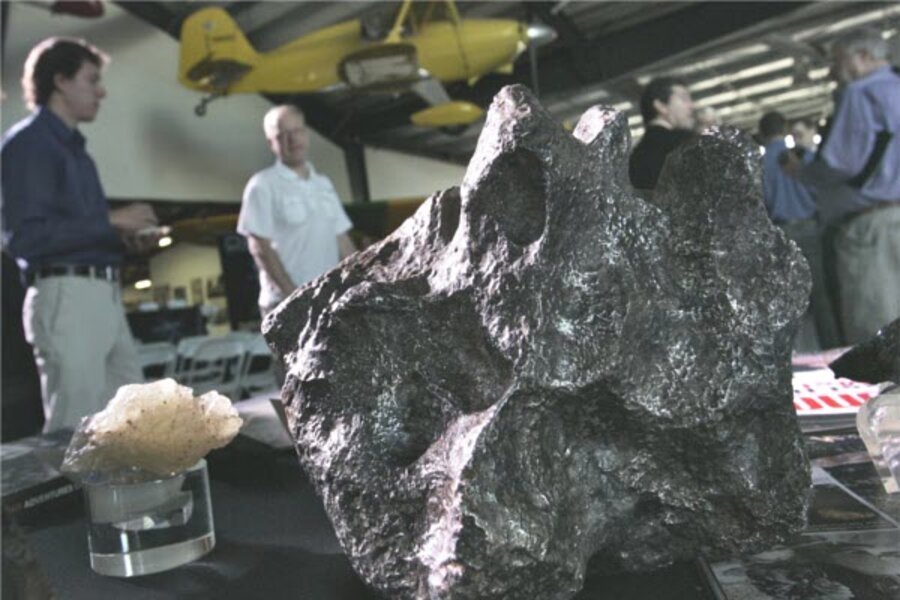

Asteroids aren't just for dodging anymore. Less than a year after a company called Planetary Resources announced plans to survey, then mine, asteroids, a second company has set out its plans to turn orbiting piles of cosmic rubble into rocket fuel, solar panels, and trusses for spacecraft hundreds to thousands of miles above Earth.

Suddenly asteroid mining has the potential of becoming a competitive field.

The ultimate goal is to make space exploration and development more affordable by obtaining fuel and construction material from easy-to-reach sources that flit past Earth all the time, rather than the costlier method of hauling everything up from Earth.

As a start, representatives of Deep Space Industries (DSI) on Tuesday outlined the company's plans to launch small prospector missions to asteroids beginning in 2015. A year later, the firm plans to launch its first sample-return mission, which aims to bring back samples of an asteroid not by the cupful, but in 60- to 150-pound quantities.

Such amounts not only would present a bonanza for the research community. They also would provide pristine test material for mining, refining, and manufacturing techniques the company is developing for use in space.

To company chairman Rick Tumlinson, DSI's ultimate goals represent a logical next step beyond government-sponsored exploration programs. He drew an analogy between NASA's human-spaceflight program and the Lewis and Clark Expedition under Thomas Jefferson, which was followed by a westward flow of settlers.

"We are the settlers and shopkeepers" heading into this latest frontier, he added.

Over the past 32 years, astronomers have discovered about 9,000 near-Earth asteroids, largely with the goal of assessing the risk of a collision with Earth. But among those 9,000, about 1,700 require only about as much energy to reach as a trip to the moon – an alluring prospect for cosmic prospectors interested in exploiting the asteroids' resource potential.

For all the various elements asteroids may provide – from platinum to iron and silicon – perhaps the most immediately valuable resource they carry is water ice, which can be used to make rocket fuel.

Therein lies the early money, according to officials with DSI and with Planetary Resources.

One early market, DSI officials say, could well be communications satellites. These run out of fuel long before their hardware fails. Although in principle these satellites could be refueled, sending that fuel from Earth is prohibitively expensive. So, before their tanks run dry, they must be sent to graveyard orbits where they won't collide with other satellites and become space junk. Fuel manufactured in space from water ice liberated from asteroids, however, could extend the operating life of a satellite.

Each month of additional service is worth another $5 million to $8 million to a communications-satellite operator, notes David Gump, DSI's chief executive officer.

The ability to make and pump fuel in space also could cut the cost of a mission to Mars, he adds.

The near-term objectives DSI has set for its missions in 2015 and 2016 appear more aggressive than those Planetary Resources set for itself.

Where DSI plans to launch sample return missions beginning in 2016, Planetary Resources is focusing on two types of small but powerful space telescopes for use near Earth. One type would orbit continuously, alternating its gaze from space and the hunt for undiscovered asteroids and other cosmic objects to Earth for various remote-sensing tasks. Similar telescopes with added propulsion could be used to intercept asteroids that are discovered shortly before a close encounter with Earth. A third, more-capable class, would be sent to take the measure of distant asteroids.

For private mining enterprises to thrive in space, however, you need more than a few robotics engineers, deep-pocketed investors, an d a ride into space, some specialists say. You also need a legal framework that defines property rights in ways that give investors confidence that the stake you claimed won't get jumped, leaving you with no recourse.

Under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, for instance, no country can lay claim to another celestial body, including an asteroid. But it was silent on the issue of individual claims to a chunk of space rock.

The 1979 Moon Treaty was supposed to close that gap, notes Frans von der Dunk, a law professor at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln who specializes in space law. Among other things, the treaty bans individual or corporate ownership of any celestial object. The only organization that can claim jurisdiction must be international and governmental.

But the treaty "has remained a dead letter except for a few countries of minor space-faring status," he says. The big players want to keep their options open.

At the moment, outside of compliance with any applicable US laws, no law prevents either company from mining asteroids, Dr. von der Dunk explains. Nor is there a law to prevent anyone from landing a monster scoop next door and mining the same ice-rich deposit of rubble.

That could change as either company, or any additional entries into the moon or asteroid-mining arena, get much closer to scraping space dirt.

Indeed, the time to start crafting some form of property-rights regimes for space is now, rather than later when more capital has been invested in the mining business, von der Dunk suggests. Wait too long, and incentives to act could be thwarted by those vested interests who would prefer a more Wild West approach to mining.

The time to devise "a sensible and balanced regime" for exploiting space resources is well in advance of "the first actual activities," he says.