Where does the solar system end? Voyager 1 probe to find out, eventually.

Loading...

NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft, which launched 35 years ago today (Sept. 5), surprisingly may have far more to travel before it leaves the solar system, researchers say.

How much more is up for debate. The scientists say their new finding suggests much about the outer reaches of the solar system remains unknown.

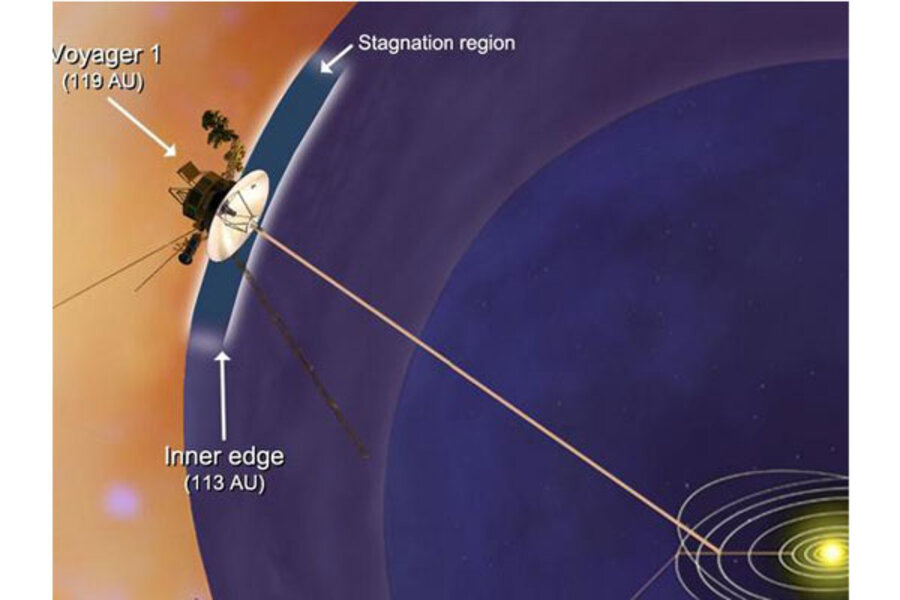

Voyager 1, which left Earth on Sept. 5, 1977, is about 11.3 billion miles (18.2 billion kilometers) from the sun. Meanwhile, Voyager 2, which launched 16 days earlier on a longer trajectory, is approximately 9.3 billion miles (14.9 billion km) from the sun.

NASA launched the twin Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft to explore the outer planets in our solar system. Researchers had thought the probes, which are still occasionally beaming back data, might be exiting the solar systemby now – but the direction of the solar wind is telling them otherwise.

One way to think about the edge of the solar system is to measure it in terms of the solar wind, the stream of energetic particles pouring from the sun. The area dominated by the solar wind is known as the heliosphere.

The distant region where the solar wind slows as it begins to run into interstellar gas and dust is known as the heliosheath. The mysterious boundary where the solar wind finally ends and the interstellar medium begins is called the heliopause.

Past research suggested the Voyager probes were entering an unknown part of the heliosheath (dubbed the "transition zone" or the "stagnation region") where the flow of solar wind had apparently calmed down. Scientists thought that by now Voyager 1 would start to see the solar wind deflected from its straight outward path into a more northward or southward manner as it curved to form the heliopause. [Photos from NASA's Far-Flung Voyager Probes]

Now researchers using data from the Voyager 1 spacecraft find the probe is not yet close to the heliopause.

"The implication is that the flow of solar wind plasma in the heliosheath is more complex that we had expected," study lead author Robert Decker, a space physicist at Johns Hopkins University, told SPACE.com.

Decker and his colleagues requested that the Voyager project team rotate Voyager 1 periodically to see if the solar wind was in fact getting deflected in a northward or southward manner. They found no evidence of deflection in the zone the probe was zipping through.

It remains uncertain how much farther outward the transition region extends, researchers say. As to when Voyager 1 might actually leave the heliopause, "opinions vary on this," Decker said. "Based on the changes we have seen in the Voyager 1 data during the past year, I would expect that Voyager 1 will cross the heliopause within one year."

Decker and his colleagues detail their findings in the Sept. 6 issue of the journal Nature.

NASA's Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft amazed astronomers with close-up views of the gas giant planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune during their tag-team mission. Voyager 2, which launched Aug. 20, 1977, is currentlyNASA's longest running mission ever.

Each Voyager probe carries a golden record with a collection of sights and sounds from Earth, just in case the spacecraft are discovered by intelligent beings in interstellar space.

The recordings include 117 images of Earth, animals and humans, as well as greetings in 54 languages, with a variety of natural and human-made sounds like storms, volcanoes, rocket launches, airplanes and animals. The collection was chosen by a committee chaired by Cornell University astronomer Carl Sagan.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

- 5 Facts About NASA's Far-Flung Voyager Spacecraft

- Humankind's First Venture Into Interstellar Space Underway? | Video

- Quiz: How Well Do You Know Our Solar System?

Copyright 2012 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.