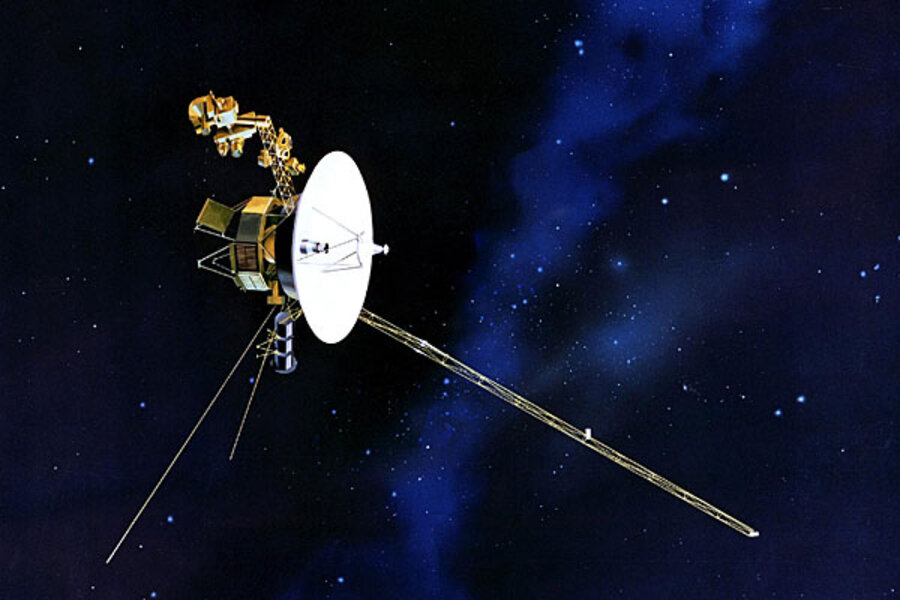

Voyager 1 soars into uncharted space, 11 billion miles from the sun

Loading...

| Pasadena, Calif.

Thirty-five years after leaving Earth, Voyager 1 is reaching for the stars.

Sooner or later, the workhorse spacecraft will bid adieu to the solar system and enter a new realm of space — the first time a manmade object will have escaped to the other side.

Perhaps no one on Earth will relish the moment more than 76-year-old Ed Stone, who has toiled on the project from the start.

"We're anxious to get outside and find what's out there," he said.

When NASA's Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 first rocketed out of Earth's grip in 1977, no one knew how long they would live. Now, they are the longest-operating spacecraft in history and the most distant, at billions of miles from Earth but in different directions.

Wednesday marks the 35th anniversary of Voyager 1's launch to Jupiter and Saturn. It is now flitting around the fringes of the solar system, which is enveloped in a giant plasma bubble. This hot and turbulent area is created by a stream of charged particles from the sun.

Outside the bubble is a new frontier in the Milky Way — the space between stars. Once it plows through, scientists expect a calmer environment by comparison.

When that would happen is anyone's guess. Voyager 1 is in uncharted celestial territory. One thing is clear: The boundary that separates the solar system and interstellar space is near, but it could take days, months or years to cross that milestone.

Voyager 1 is currently more than 11 billion miles from the sun. Twin Voyager 2, which celebrated its launch anniversary two weeks ago, trails behind at 9 billion miles from the sun.

They're still ticking despite being relics of the early Space Age.

Each only has 68 kilobytes of computer memory. To put that in perspective, the smallest iPod — an 8-gigabyte iPod Nano — is 100,000 times more powerful. Each also has an eight-track tape recorder. Today's spacecraft use digital memory.

The Voyagers' original goal was to tour Jupiter and Saturn, and they sent back postcards of Jupiter's big red spot and Saturn's glittery rings. They also beamed home a torrent of discoveries: erupting volcanoes on the Jupiter moon Io; hints of an ocean below the icy surface of Europa, another Jupiter moon; signs of methane rain on the Saturn moon Titan.

Voyager 2 then journeyed to Uranus and Neptune. It remains the only spacecraft to fly by these two outer planets. Voyager 1 used Saturn as a gravitational slingshot to catapult itself toward the edge of the solar system.

"Time after time, Voyager revealed unexpected — kind of counterintuitive — results, which means we have a lot to learn," said Stone, Voyager's chief scientist and a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology.

These days, a handful of engineers diligently listen for the Voyagers from a satellite campus not far from the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which built the spacecraft.

The control room, with its cubicles and carpeting, could be mistaken for an insurance office if not for a blue sign overhead that reads "Mission Controller" and a warning on a computer: "Voyager mission critical hardware. Please do not touch!"

There are no full-time scientists left on the mission, but 20 part-timers analyze the data streamed back. Since the spacecraft are so far out, it takes 17 hours for a radio signal from Voyager 1 to travel to Earth. For Voyager 2, it takes about 13 hours.

Cameras aboard the Voyagers were turned off long ago. The nuclear-powered spacecraft, about the size of a subcompact car, still have five instruments to study magnetic fields, cosmic rays and charged particles from the sun known as solar wind. They also carry gold-plated discs containing multilingual greetings, music and pictures — in the off chance that intelligent species come across them.

Since 2004, Voyager 1 has been exploring a region in the bubble at the solar system's edge where the solar wind dramatically slows and heats up. Over the last several months, scientists have seen changes that suggest Voyager 1 is on the verge of crossing over.

When it does, it will be the first spacecraft to explore between the stars. Space observatories such as the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes have long peered past the solar system, but they tend to focus on far-away galaxies.

As ambitious as the Voyager mission is, it was scaled down from a plan to send a quartet of spacecraft to Jupiter, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto in what was billed as the "grand tour" of the solar system. But the plan was nixed, and scientists settled for the Voyager mission.

American University space policy expert Howard McCurdy said it turned out to be a boon.

They "took the funds and built spacecraft robust enough to visit all four gas giants and keep communicating" beyond the solar system, McCurdy said.

The double missions so far have cost $983 million (€782.15 million) in 1977 dollars, which translates to $3.7 billion (€2.94 billion) now. The spacecraft have enough fuel to last until around 2020.

By that time, scientists hope Voyager will already be floating between the stars.

___

Copyright 2012 The Associated Press.