Antarctica started warming 600 years ago, study finds

Loading...

| Oslo

Temperatures in the Antarctic Peninsula started rising naturally 600 years ago, long before man-made climate changes further increased them, scientists said in a study on Wednesday that helps explain the recent collapses of vast ice shelves.

The study, reconstructing ancient temperatures to understand a region that is warming faster than anywhere else in the southern hemisphere, said a current warming rate of 2.6 degrees Celsius (4.7 Fahrenheit) per century was "unusual" but not unprecedented.

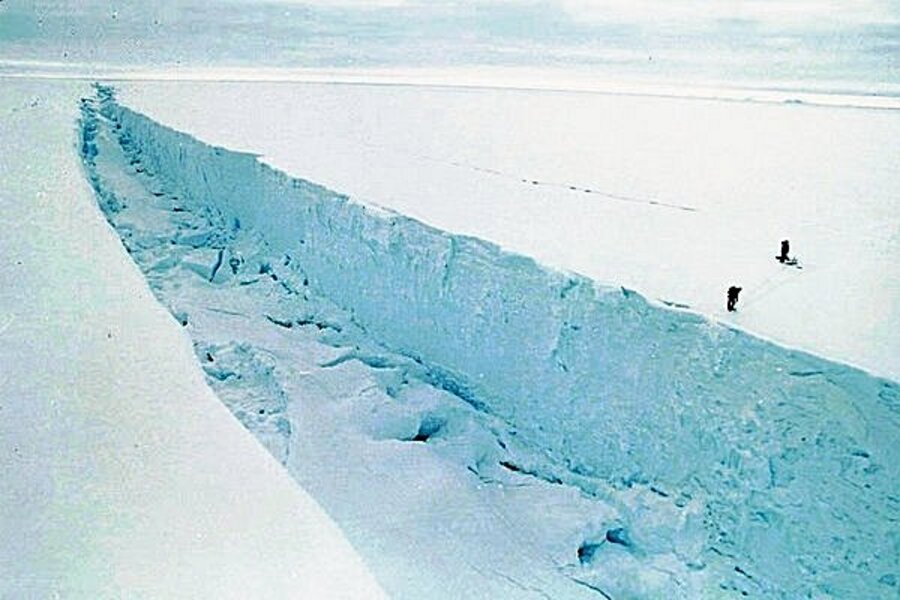

"By the time the unusual recent warming began, the Antarctic Peninsula ice shelves were already poised for the dramatic break-ups observed from the 1990s onwards," said the British Antarctic Survey, which led the study published in the journal Nature.

A warming trend caused by natural variations, perhaps affecting winds and ocean currents, began 600 years ago and made ice shelves - tracts of ice floating on the ocean around the peninsula - vulnerable to even faster warming since 1920.

Several ice shelves around the peninsula have collapsed in recent years, including the Larsen A and B shelves and the Wilkins. About 25,000 sq km (9,500 sq miles) of ice has been lost, roughly the size of Haiti.

Burning of fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century has emitted heat-trapping greenhouse gases, raising temperatures and causing floods, droughts and rising sea levels as ice melts, according to a U.N. panel of scientists.

Human causes

"What we are seeing is consistent with a human-induced warming, on top of a natural one," Robert Mulvaney, lead author at the British Antarctic Survey, told Reuters. He cautioned that the study, conducted with experts in Australia and France, only referred to one small part of Antarctica.

The scientists dug a core of ice, with year-by-year clues to temperatures, 364 metres (398 yards) deep on James Ross Island at the north of the peninsula to examine records back 15,000 years.

The loss of floating ice shelves does not itself raise sea levels because the water is already part of the ocean. But glaciers on land can start sliding faster towards the sea and add water when shelves holding them back vanish.

Glaciers on the peninsula are small by the standards of Antarctica, which contains enough ice to raise world sea levels by about 60 metres if it ever all melted. Even a small thaw would threaten low-lying nations and cities.

"If this rapid warming that we are now seeing continues, we can expect that ice shelves further south along the peninsula that have been stable for thousands of years will also become vulnerable," said Nerilie Abram, of the Australian National University.

The scientists said temperatures on the peninsula had been slightly higher than now about 11,000 years ago near the end of the last Ice Age, and some ice shelves retreated. A long cooling period ended around 600 years ago.

Separately in Nature, researchers monitoring Himalayan glaciers said that they had found evidence of a slight overall thaw in recent years - slightly more of a melt than in another recent study - in what they said was the most detailed overview of the world's highest mountain range.

Glaciers feed rivers such as the Ganges, the Mekong and the Yangtze and their flows are vital for food production.

The U.N. panel of climate scientists had to correct a 2007 report about the impacts of climate change after wrongly projecting that all Himalayan glaciers might melt by 2035 - far faster than scientists project.

"There is no runaway melt. Most of the glaciers are melting at a similar rate to other glaciers in the world," lead author Andreas Kaab at the University of Oslo told Reuters of the study of glaciers in the Hindu Kush, Karakoram and Himalayas.

(Editing by Alessandra Rizzo)