NASA to launch new mission to Mars to probe below the crust

Loading...

In 2016, NASA's Mars rover Curiosity will get a companion – a new lander that aims to help scientists figure out how the planet formed and evolved, from core to crust.

In doing so, the project could shed additional light on how a planet that could have been hospitable to life early in its history became so hostile to it today, at least on the surface.

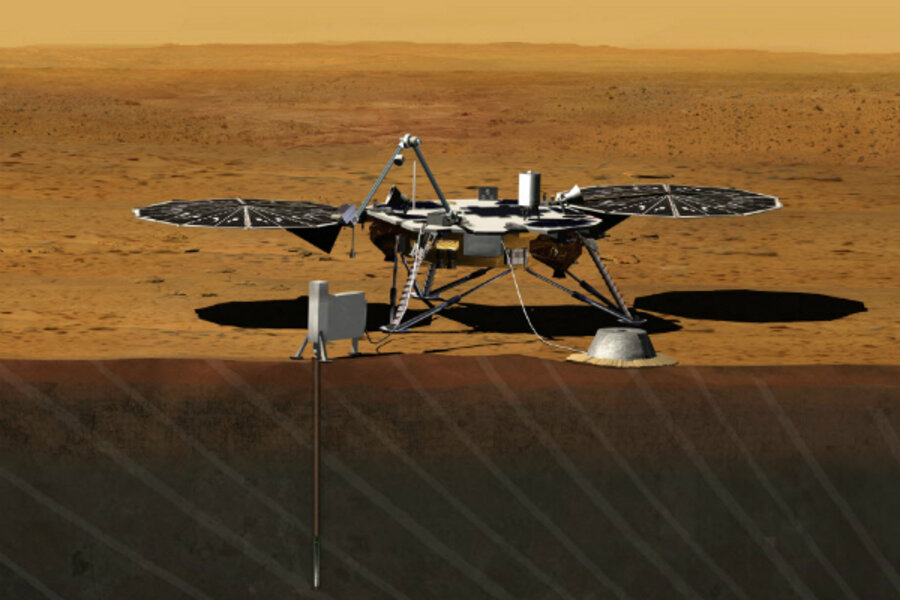

NASA officials announced the mission during a briefing late Monday afternoon. Known as InSight, the lander aims to use a seismometer to determine the size, makeup, and current condition of the planet's core, develop a profile of the planet's crust, analyze its mantle, measure the planet's marsquake activity, and measure the rate at which meteors are striking the planet's surface. In addition, the lander will sink a probe several meters into the soil to help estimate how the planet's temperature varies with depth.

As for habitability, on a planetary scale what goes on under the crust can be just as important as what goes on at the surface, astrobiologists note.

Global magnetic fields – which Mars no longer has – can deflect cosmic rays and charged particles from solar storms, which can threaten organisms on the surface. Earth's magnetic field results from the motions of an electrically conductive molten-iron outer core. On Mars, this dynamo has shut down.

On Earth, heat from the core also drives plate tectonics – a planetary heat-exchanger in which the crust is constantly recycled between taffy-like material in the mantle and solid surface. Tectonics triggers volcanism, whose gases can play an enormous role in readjusting the composition of a planet's atmosphere – including the amount of water vapor – and hence its climate.

Does Mars have active tectonics today? "We just don't know," says John Grunsfeld, NASA's associate administrator for the agency's science-mission directorate.

This mission falls under the agency's Discovery program, which focuses on relatively low-cost missions whose hardware costs are capped at $425 million. Curiosity, by contrast, is part of the NASA's Mars Exploration Program. And the cost of its mission is estimated at $2.5 billion.

Despite it's relatively low cost, InSight aims to answer questions planetary scientists have been asking about the Red Planet for decades, Dr. Grunsfeld explained during the briefing.

"We're very confident that this will produce exciting science," Grunsfeld said.

The mission beat two other finalists for this round of Discovery missions. A proposed Comet Hopper mission would put a lander on comet 46P/Wirtanen, where it would study the comet's composition and track changes in its nucleus as it moves through its orbit. The lander would have included thrusters that would allow it to "hop" from one location on the nucleus to another. Another mission would have essentially sent a high-tech buoy to a vast methane sea on Saturn's moon Titan to study its composition and its interaction with the atmosphere.

All contained compelling science, Grunsefeld said. But InSight was the only one that project reviewers inside and outside NASA felt stood the best chance of coming in at or under the Discovery program's $425 million cost cap, excluding launch costs, and within the tight schedule the program demands.

With budgets facing an ever tighter squeeze from Congress and the White House, the agency could ill afford delays that would stretch out other Discovery missions and boost their costs, Grunsfeld said.

One reason InSight looked like a safer financial bet is that it is based on lander and entry-stage designs developed for the Mars Phoenix Lander, and the failed Mars Polar Lander before it. Phoenix landed successfully and spent five months in 2008 studying a site in Mars' Arctic region.

InSight, by contrast, is slated to land near Mars' equator and operate for at least two years.

At first blush, Mars might look like a tectonic has-been. But over the past decade, orbiters detected landslides, uncovered tenuous hints of methane in the atmosphere, which can have a geothermal origin, and some scientists say they have seen surface features that suggest faults.

Indeed, in early August, An Yin, a geophysicist at the University of California at Los Angeles, published an analysis of images of Mars' Valles Marineris, the solar system's larges canyon, and pointed to evidence that two large crustal plates are sliding past each other. The fault defining the boundary runs along the length of the nearly 2,500 mile-long scar in the Martian crust.

Dr. Yin saw in the images what he interprets as features that are offset on either side of the fault by about 93 miles. Compared with Earth, Mars is smaller and its interior cooler, so it would have fewer plates. And those it has would move much more slowly than Earth's plates do.

The fault may become active every million years or so, he estimates. The results were published recently in the journal Lithosphere.