Amelia Earhart search to continue despite lack of hard evidence

Loading...

| Honolulu

Even though a monthlong voyage for Amelia Earhart's plane wreckage turned up nothing definitive, the searchers devoted to the hunt say they have a trove of evidence to examine that will help shed light on what happened to the famed aviator 75 years ago.

The expedition to a remote atoll roughly 2,000 miles (3,200 kilometers) southwest of Hawaii was well on its way back to Honolulu on Tuesday as Earhart's family and others marked what would have been the American icon's 115th birthday.

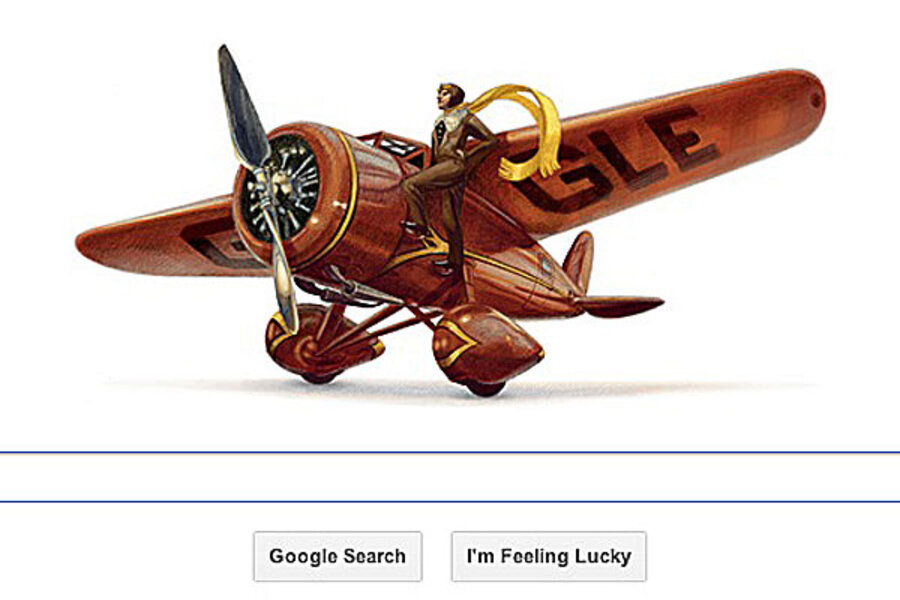

Google honored Earhart by changing the logo on its homepage, while her family said on their website that Earhart's legacy remains relevant.

"The aviation pioneer, who was the first female pilot to cross the Atlantic Ocean, continues to make lasting impressions on people all over the world," the statement posted Tuesday said.

Pat Thrasher, president of The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery, said plans are already in the works for a land-based expedition to the Kiribati atoll of Nikumaroro next year.

The voyagers looked at footage as it initially came in from a tethered underwater vehicle rigged with cameras and lights. But the group expects to learn more through repeat viewings, picking up new insights on the underwater landscape where they believe the plane went down. The group has countless hours of high-definition video and sonar data.

"It's unbelievably difficult as an environment and your eyeballs fall out after a while" watching the video, Thrasher said. "The only way you can be sure you know what you found is to go back through the data very carefully."

The expedition cost $2.2 million. The group was short nearly $500,000 at the start of the voyage and will need to raise more funds for any future trips.

But the group still believes Earhart and her navigator crashed onto a reef off the remote island, Thrasher said.

Remnants of the plane, the group believes, could be in hard-to-see caves within a reef that drops like a cliff thousands of feet underwater. Or, it might have simply floated away to another area that's impossible to predict.

"This is just sort of the way things are in this world," TIGHAR president Pat Thrasher said. "It's not like an Indiana Jones flick where you go through a door and there it is. It's not like that — it's never like that."

Thrasher maintained touch throughout the search with the group's founder Ric Gillespie, her husband, and posted updates about the trip to the group's website. The updates tell of a search that was cut short because of treacherous underwater terrain and repeated, unexpected equipment mishaps that caused delays and left the group with only five days of search time rather than 10, as originally planned.

During one episode, an autonomous underwater vehicle the group was using in its search wedged itself into a narrow cave, a day after squashing its nose cone against the ocean floor. It needed to be rescued.

"The rescue mission was successful — but it was a real cliffhanger," Gillespie wrote in an email posted online last week. "Operating literally at the end of our tether, we searched for over an hour in nightmare terrain: a vertical cliff face pockmarked with caves and covered with fern-like marine growth."

Thrasher said the environment was tougher to navigate than searchers expected, and even images are difficult to distinguish.

"This was the first time any such work has been done there below scuba depth," she said.

The U.S. State Department had encouraged the privately-funded voyage, which launched earlier this month from Honolulu using 30,000 pounds (13,600 kilograms) in specialized equipment and a University of Hawaii ship normally used for ocean research.

The group's thesis is based on the idea that Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan landed on a reef near the Kiribati atoll of Nikumaroro, then survived a short time.

Previous visits to the island have recovered artifacts that could have belonged to Earhart and Noonan, and experts say an October 1937 photo of the shoreline of the island could include a blurry image of the strut and wheel of a Lockheed Electra landing gear.

The photo was enough for the State Department blessing, and led to the Kiribati government to sign a contract with the group to work together if anything is found, Gillespie said at the start of the voyage.

A separate group working under a different theory plans its third voyage later this year near Howland Island.

Earhart and Noonan were flying from New Guinea to Howland Island when they went missing July 2, 1937, during Earhart's bid to become the first woman to circumnavigate the globe.

___