Venus transit 2012: a chance to test Earth-hunting techniques

Loading...

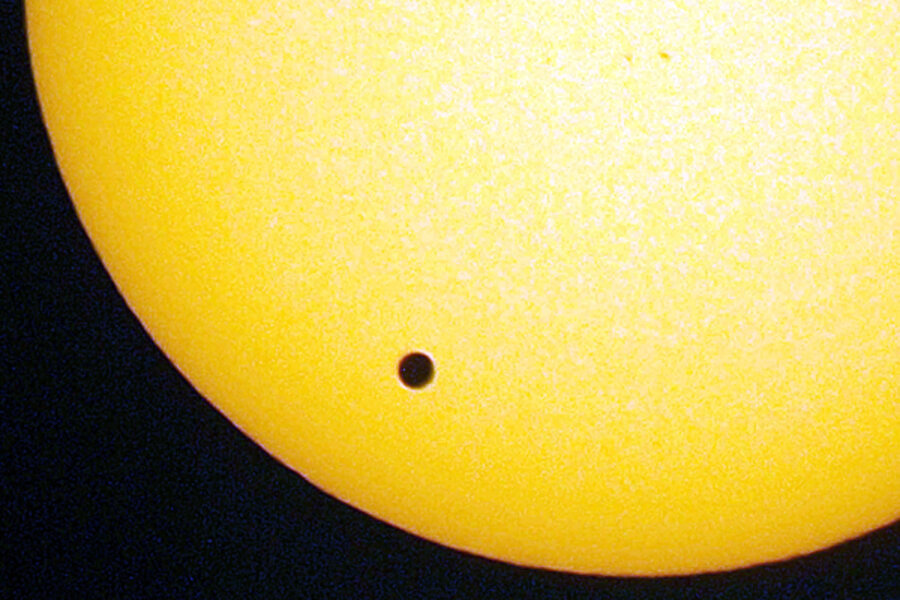

There's a little black spot on the sun today.

No you don't want to miss this rare display. (With apologies to Sting)

It's V-Day 2012, the day Venus transits the sun, appearing as a black dot against the star's searing surface. It's a show that won't make its celestial revival until December 2117.

For many skywatchers, this event is drawing eyes because it is rare and intimately tied to the history of humanity's quest to take the measure of its corner of the cosmos. In the 18th and 19th centuries, scientists risked their lives traveling to far-flung corners of the globe to carefully record the track of the first lady of the solar system across the sun. Back then, it was the best means available for trying to estimate the Earth's distance from the sun and derive a size for the solar system.

But for some astronomers, Tuesday's transit offers an unique opportunity to use Venus as a surrogate for Venus- and Earth-size planets orbiting other stars, as researchers hone their skills at analyzing potential havens for life outside the solar system.

For others, the transit could help unravel a longstanding mystery about Venus itself: What drives the "super rotation" of its atmosphere? Venus spins on its axis once every 243 days. Its atmosphere performs the same feat in four days, with winds traveling at nearly 450 miles an hour.

A long time to wait

Venus's transits owe their century-scale frequency to the orbital paths Earth and Venus trace around the sun.

Seen in relation to the plane of Earth's orbit, Venus's orbit has a slight tilt – about 3.4 degrees. Depending on where the two planets are in their respective orbits, that leaves Venus trailing the sun toward the horizon at nightfall or rising ahead of the sun before dawn. But on Tuesday the two planets' orbits are aligned in such a way that Venus will pass directly between Earth and the sun during Venus's inferior conjunction, or closest approach to Earth.

Venus's transits occur in pairs, separated by eight years – Tuesday's transit is paired with one in 2004. The pairs repeat their appearance twice in a 243-year cycle, with one return time spanning 105.5 years, and the other 121.5 years. So, if you miss this one, tell your children to tell their children to take heart. We're in a part of the cycle with the shortest return time – in December 2117.

Astronomers are working hard not to miss it.

A chance to study other Earths

Tuesday's transit represents "a great opportunity" to test approaches for studying atmospheres of Earth-scale planets orbiting sun-like stars, says Jean-Michel Desert, a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., and a member of the team conducting the experiment.

The team, led by Alfred Vidal-Madjar at the Institute for Astrophysics in Paris, will use the Hubble Space Telescope to watch the transit via the light reflected off the moon, since the orbiting observatory would be permanently blinded if it tried observing the sun directly.

The group plans to use a spectrometer aboard Hubble to track changes in the spectra of light reflecting off the moon before, during, and after the transit. Before and after the transit, the light will carry only the fingerprints of chemical elements in the sun. During the transit, however, sunlight passing through Venus's atmosphere will add chemical signatures from the planet's envelope of gases to the mix. By subtracting the "during" from the "before and after," the team expects to glean information about Venus's atmospheric recipe.

The results aren't likely to provide any new insight into Venus's atmosphere itself, Dr. Desert says. The composition of its atmosphere is already well known. The team, however, will use them to evaluate new techniques to discern the atmospheres of Earth-like planets in other solar systems.

As close as Venus and the sun are, pulling information on Venus's atmosphere out of sunlight reflected off the moon is just as challenging as trying to spot the chemical fingerprints of an atmosphere on a planet orbiting a star light-years away, Desert explains.

NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory also will be observing the transit directly and will use the sun's backlighting to analyze Venus's atmosphere as well as to use the transit itself as a means of calibrating the observatory's telescope.

Super-rotation observations

Meanwhile, another team is gathering data from solar telescopes around the world relating to the bright, thin, halo-like arc of light tracing the planet's disc as it begins and ends its pass across the sun. Scientists spotted the arc as they observed Venus's transit eight years ago. It was sunlight reflected through layers of the atmosphere above the cloud tops, forming an illuminated arc similar to those astronauts see tracing Earth's curvature at sunrise and sunset as they orbit.

By making careful measurements of this limb of light and teasing from it information about how temperatures and densities in that part of the atmosphere vary with latitude, the US-French team conducting the research hopes to provide an additional test of models that researchers have constructed to explain super rotation, says Jay Paschoff, an astronomy professor at Williams College in Williamstown, Mass. He and astronomer Thomas Widemann of the Paris Observatory are coordinating the effort, which involves nine Earth-based solar observatories, as well as two sun-watching spacecraft.

Such high-speed atmospheric circulation relative to a planet's or moon's rotation rate also has been observed on Jupiter, Saturn, and Saturn's moon Titan.

The transit is set to begin at 6:03 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time as Venus first appears to touch the sun's disk. The transit will end around 12:50 a.m. EDT June 6. As a starting point for viewing tips and other information about the transit, visit NASA's Venus-transit site.