Strange red galaxies a 'missing link' in history of the universe?

Loading...

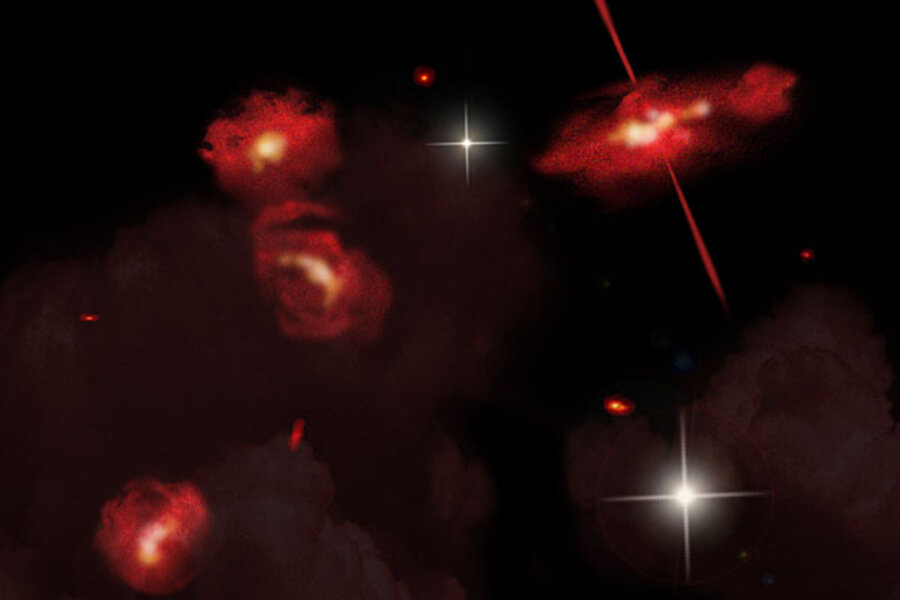

A quartet of rarely observed, ruby-red galaxies from the dawn of the universe could provide a "missing link" in understanding how galaxies formed, according to a new study.

The galaxies, which researchers estimate formed before the 13.7 billion-year-old universe had reached its one billionth birthday, were a puzzle to the team that discovered them. Only one other galaxy like them had been spotted before, and researchers sought to understand why the four galaxies were as red and dim as they appear.

The data could help scientists trying to piece together the story of how the first galaxies formed, as well as how galaxies evolved from humble beginnings to form the variety of sizes, shapes, and star populations seen today in nearby regions of the universe.

These galaxies "might be a missing link in galactic evolution," notes Giovanni Fazio, a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., and a member of the team reporting the results, in a statement.

The galaxies appeared in data gathered by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope, which observes at longer infrared wavelengths than Hubble. That means Spitzer is in a better position to snag objects – like these galaxies – that shine more brightly in the infrared than in visible wavelengths.

"Hubble has shown us some of the first protogalaxies that formed, but nothing that looks like this," said Dr. Fazio.

Still, the international team reporting the results pushed data-analysis techniques to their limit to tease out the dim galaxies. The team, headed by the Center for Astrophysics' Jiasheng Huang, also had to grapple with why the galaxies were so red and dim. Three options seemed possible:

- The galaxies could host a large population of older, redder stars and be somewhat closer than the 12.7 billion light-year distance.

- They could be extremely dusty and even closer.

- They could be so distant that the universe's expansion has stretched the wavelengths of light they emit deep into the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

After analyzing the possibilities, the team determined that a blend of the 12.7 billion light-year distance with lots of dust best fit the data. In other words, the redness was not a trick of the distance; these neighboring galaxies would still be red if observed by someone in their local patch of the cosmos.

Red and rockin'. The team notes that one of the four objects is an X-ray quasar, typically an indicator of an active supermassive black hole at its center. Another is a hyper-luminous infrared galaxy.

Both point to galaxies that are undergoing mergers, the team suggests. And where there are mergers, more stars are born.

Initial estimates put the galaxies' masses at roughly 10 to 30 percent of the Milky Way's mass, which itself estimated at between 1 trillion and 1.5 trillion times the sun's mass.

The data were gathered as part of the Great Observatories Origins Deep Survey. The international effort draws on US and European orbiting observatories as well as ground-based telescopes observing in a range of wavelengths. It is designed to study galaxies over a wide span of time scales, peering as deep into the universe's past as current technology allows.

The next step will be to follow up the Spitzer observations with views from telescopes that look at the universe with submillimeter views. These telescopes are specifically designed to see dusty and hidden objects that other telescopes can barely see, if at all.

For example, the Submillimeter Array near the summit of Hawaii's Mauna Kea discovered the only other known galaxy like those in the new quartet.

The researchers say they hope to gather more-accurate distance-related data for the newly found galaxies with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimater Array (ALMA) high in Chile's Atacama Desert. The array began its first science operations in August.