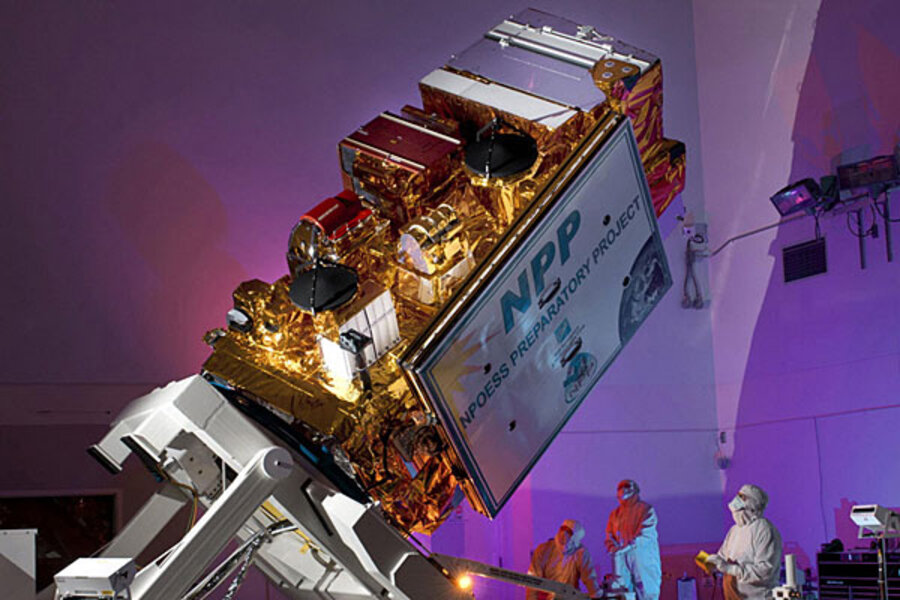

Prototype of next-generation weather satellite: Can it go to work fast enough?

Loading...

The US is set to launch a prototype weather satellite in the pre-dawn hours Friday morning, a milestone toward the deployment in five years of a much-needed new generation of weather and climate satellites.

A successful launch at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California, set for 2:48 a.m. Pacific Daylight Time, would represent a significant achievement for the program – one that has been delayed by technical challenges, mismanagement, cost-overruns, and a subsequent restructuring of the effort.

That explains why officials, during pre-launch briefings earlier this week, universally expressed their excitement at finally seeing a satellite sitting atop a rocket on the launch pad.

The craft is the first designed “to provide observations for both weather forecasters and climate researchers,” says Jim Gleason, a researcher at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Institute in Greenbelt, Md., and the mission's project scientist.

Known by its initials NPP, the mission is designed to collect some 30 different kinds of data ranging from the amount of solar energy the Earth receives and reflects, to measurements of temperature and water vapor, to tracking changes in vegetation on land and plankton at sea.

Four of the spacecraft's five instruments have never flown before, although they will be observing the same weather and climate features that instruments on previous missions have measured.

The five-year NPP mission is designed to give these four instruments a rigorous shake-down cruise, as well as to iron out any kinks in the ground network established to receive and distribute the large amounts of data the craft is designed to deliver.

Orbiting over the poles at an altitude of some 512 miles, the craft is expected to beam 800 DVDs' worth of information back to Earth each day.

And while the mission is largely a test drive for the satellite and ground systems, forecasters with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration will be folding the satellite's information into their weather forecasts from the beginning.

Satellite data form “the backbone” of information computer models need to help forecasters anticipate weather conditions, notes Mitch Goldberg, chief of satellite meteorology and climatology at NOAA and the program scientist for the new generation of weather satellites the NPP mission is supporting.

The data these satellites are designed to deliver will be crucial as NOAA strives to stretch the lead time for severe-weather forecasts, particularly those dealing with hurricanes, from the current five-day outlooks to seven days, Dr. Goldberg says.

And for climate researchers, the NPP satellite will extend long-term measurements of key aspects of Earth’s climate.

This mission is a key piece of a project originally known as the National Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System. NPOESS was established in 1994 as a joint effort of the Pentagon, NASA, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The goal was to develop a fleet of six identical satellites orbiting the poles that could meet the needs of the Pentagon and NOAA for improved weather forecasts while also carrying instruments to monitor key features of Earth's climate over long periods of time for NOAA and NASA's climate research needs.

But technical setbacks and mismanagement boosted the price of the program to $13.9 billion, compared with the original estimate of $6.5 billion.

The program's troubles led to a five-year slip in the launch schedule and restructuring. With no small prod from Congress and from an independent review panel, the Obama administration last year restructured the effort.

The Pentagon would continue to rely on its own weather satellites, several of which are still in the pipeline. NOAA and NASA would work together on a joint polar-satellite system (JPSS) – a fleet of two orbiters, for launch in 2016 and 2019.

Friday's launch of the NPOESS Preparatory Project satellite was originally envisioned for early 2006.

Because research satellites such as NASA's Terra, Aqua, and Aura orbiters will be reaching the end of their missions over the next two to three years, NPP is seen as an important bridge to keep the kind of data these other orbiters delivered flowing until the JPSS satellites launch.

"NPP is very important," says Rick Anthes, president of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, which oversees the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo. Even with a successful NPP mission, the US will see the number of Earth-observing satellites it launches dwindle, just as the environmental questions they are designed to answer grow in importance.

A reduction in Earth remote-sensing capabilities, he says, would be one more signal that the US is ceding its leadership in space to Europe and Asia, to its competitive disadvantage.