Huzzah, summer solstice? At South Pole, winter solstice is party time.

Loading...

It's fleeting, so get ready: The Northern Hemisphere's summer solstice will come and go at 1:16 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time Tuesday.

From the sun's perspective, the June solstice marks the moment when the northern "end" of Earth's tilted axis reaches its maximum nod toward the sun.

From Earth's perspective, the summer solstice marks the highest spot the sun will reach in the sky, giving Northern Hemispherians their longest period of daylight for the year. By 1:17 p.m., the sun will have in effect said "enough" and will slowly head south for the northern winter and southern summer.

Prior to the arrival of Christianity to northern Europe, cultures celebrated the arrival of the June solstice because it was seen as one of the few times of the year when magic was at its most powerful.

These days, the June solstice is celebrated as the start of summer, although at tourist destinations such as Massachusett's Cape Cod, Memorial Day often marks the start of the "summer season" for tourism.

But lest we think of the June solstice only in terms of suntan oil or maypole dances marking "midsummer" solstice celebrations in the Northern Hemisphere, it's also an opportunity to pause and remember those who are sacrificing their summer so that others may learn about climate, or Mars, or the cosmos as a whole – never mind penguins, fossils, and krill.

These are the technicians and support people at research stations in Antarctica at the bottom of the Earth, who are currently isolated by winter storms and perpetual darkness. They, too, celebrate the June solstice – but for endurance, rather than religious, reasons.

"You have to understand that at the South Pole, the winter is very long; you basically have nine months without sunlight. That's a pretty long time," says Ralf Auer, a computer specialist with the ICECUBE neutrino experiment, located at the National Science Foundation's Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station.

With the arrival of the solstice, "you're basically getting closer and closer to the day you're supposed to see sunlight again. People are really excited about it," he says, now comfortably situated in an office in Madison, Wis., where the research project is headquartered.

Mr. Auer served at the South Pole Station from October 2009 to November 2010, ensuring that the huge experiment kept running.

The environment may be unusual. The celebration isn't. No bonfires or maypoles, to be sure. But the 50 or so winter-over residents look forward to plenty of food and dancing.

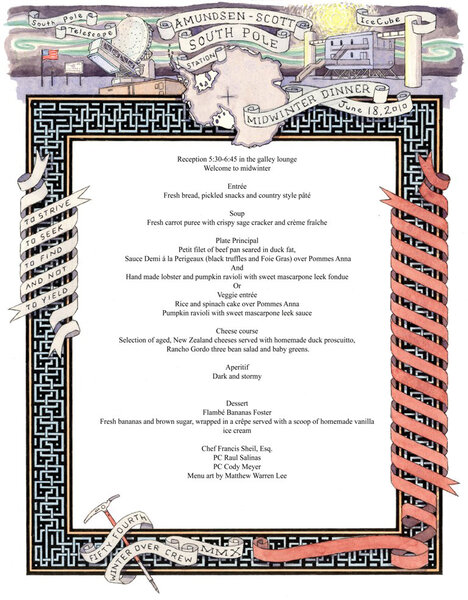

The celebration begins with a predinner reception, followed by a multicourse meal where the kitchen staff "really goes over the top," Auer says.

Food is a major morale issue when living in an isolated area for long periods. "Bad food, bad mood" is the catch phrase, he says.

After dinner, the multitude dons parkas and balaklavas, then braves the midwinter temperatures for an outdoor class photo.

It's a tough photo shoot. People are willing to throw back parka hoods, and yank off hats and full-face-cover balaklavas for a couple of seconds so the photo contains recognizable people, rather than oversized Pillsbury Dough Boys (and Girls) in official-issue NSF scarlet. But a couple of seconds is about all they can endure before they need to put the cold-weather head-gear back on.

With a class photo in the can, it's time for a party in a staff lounge festooned with printouts and photos bearing solstice greetings from other research stations dotting the continent.

And the countdown until the first fresh faces arrive in mid- to late October begins.