Meteor shower August 2010: how you can get the best view

Loading...

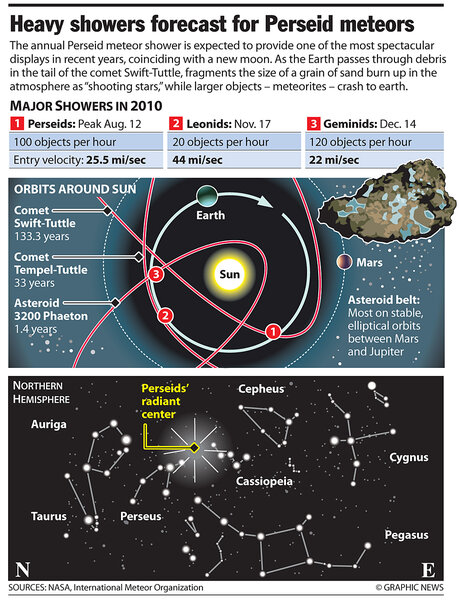

The annual Perseid meteor shower, one of the finest shows in August's night sky, is set to dazzle the bleary-eyed in the wee hours of Friday.

If you live under very dark skies or can travel beyond the sky glow of urban America, you can expect to see up to 75 meteors an hour, astronomers suggest. If you're hardy enough to be on a mountaintop, the number could reach 108 meteors an hour.

The best viewing locations will be in the Northern Hemisphere, with Southern Hemisphere sky-watchers limited to perhaps 30 or 40 events an hour at the shower's peak.

Of more than 364 meteor showers on the roster kept by the International Astronomical Union, the Perseids turn in the most reliably decent show of the bunch. (But not all 364 on the roster have been confirmed as independent meteor displays.)

This year's Perseid show is poised to be above average. So give it up for 109P/Swift-Tuttle, the comet whose debris is responsible for the show. It swings around the sun once every 135 years, spewing dust and gas as it nears the sun and heats up. The comet's last pass was in 1992.

In mid-July, Earth began moving into Swift-Tuttle’s stream of dust. The debris "is a very old stream that has been building for a long time and is a very dense concentration of dust," says Peter Jenniskens, a meteor researcher at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif.

Indeed, "if you look back at records from the Middle Ages, you can see that people in the Middle Ages were seeing the Perseid meteor shower," he says.

Swift-Tuttle originated in the Oort cloud, a vast spherical cloud of frozen leftovers from the solar system's formation some 4.6 billion years ago. Roughly 160,000 years ago, as Swift-Tuttle was passing through to the inner solar system, Jupiter captured it, sort of.

That event shrank the comet's orbit around the sun. But Jupiter's gravity was never able to draw Swift-Tuttle into its fold of truly short-period comets, which reappear on average every 20 years or less. Instead, the newcomer joined the likes of Halley's comet, which have orbital periods ranging from about 20 to 200 years.

To be sure, Swift-Tuttle crosses Jupiter's orbit with each tour through the solar system, Mr. Jenniskens explains. But Swift-Tuttle is stealthy: Jupiter is never close enough to the comet during those passes to significantly alter its travel path.

Each pass of the comet ever so slowly thickens the dust stream it leaves behind.

This year's display is unlikely to match last year's, when the shower had three peaks – one of which topped 200 meteors an hour. But the 2010 event is benefiting from two conditions that promise to keep the display above average.

First, it's happening during a new moon, which means faint meteors will not have to compete with moonlight for your attention.

Second, Earth will be passing through a denser patch of Swift-Tuttle's dust stream than usual, according to William Cooke, who heads NASA's Meteroid Environment Office at the Marshall Spaceflight Center in Huntsville, Ala. The main dust stream got a slight stir from Saturn, and we're also running into a patch of material the comet off-loaded in 1479, Cooke explains.

To get an idea of how the peak of the Perseids – and that of many other meteor showers – could appear in your area, head over to the "Fluxtimator." Select the meteor shower, nearest major urban area, viewing conditions, and date, and the graph will automatically adjust itself to give you the peak viewing time at your location and how many "shooting stars" you may be able to see.

One encouraging note, courtesy of the Fluxtimator: If you miss the show early Friday morning, plenty of meteors will still be visible at about the same times early Saturday morning.

The meteors appear as though they are emerging from a patch of the sky containing the constellation Perseus – hence the name. That constellation is high enough in the night sky by midnight Thursday to begin the show.

You can find detailed viewing tips, including pointers for taking pictures of the shower, at the American Meteor Society's website.