'Life as we don't know it' in the universe? Start with Titan.

Loading...

Scientists studying the Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, are beginning to challenge perhaps the most commonly repeated five words in the search for life in the universe.

“Life as we know it.”

From the dun plains of Meridiani on Mars to the “cool Jupiter” exoplanet CoRoT-9b circling a distant star in the constellation Serpens, scientists have put a premium on finding worlds that have the potential for liquid water, which enables life on Earth.

But in Titan, scientists have found a world that, some suggest, could point to an exception to the rule. Might life exist without liquid water? Increasingly, Titan is becoming the focus of a movement to consider the possible existence of “life as we don’t know it.”

The emphasis on “life as we know it” is understandable. After all, with “life as we know it,” scientists have at least some idea of what to look for. If life exists on Titan, it would be something that is currently only in the realm of imagination – or beyond it.

William Bains of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology thinks it would smell about as pleasant as the average carton of rotting eggs. The reason? The chemicals on offer for organisms to metabolize – for example, hydrogen sulfide and phosphine – “are truly horrible chemicals – to us,” Dr. Bains told Space.com.

Jonathan Lunine of the University of Arizona is not even sure scientists would know life on Titan if they saw it. “We would have to look for peculiarities in composition” – looking at what chemicals are where and then trying to tease out signs of potential life from the data, he told Space.com.

Why Titan?

Bains and Dr. Lunine are hesitant to suggest that this sort of life could exist.

But so, too, are they hesitant to say absolutely that life can develop only by processes familiar to humans. And since the Cassini spacecraft arrived at the Saturn system in 2004, its images of Titan have forced scientists to consider processes never before seen.

Titan is, in many ways, the closest thing in the solar system to Earth itself.

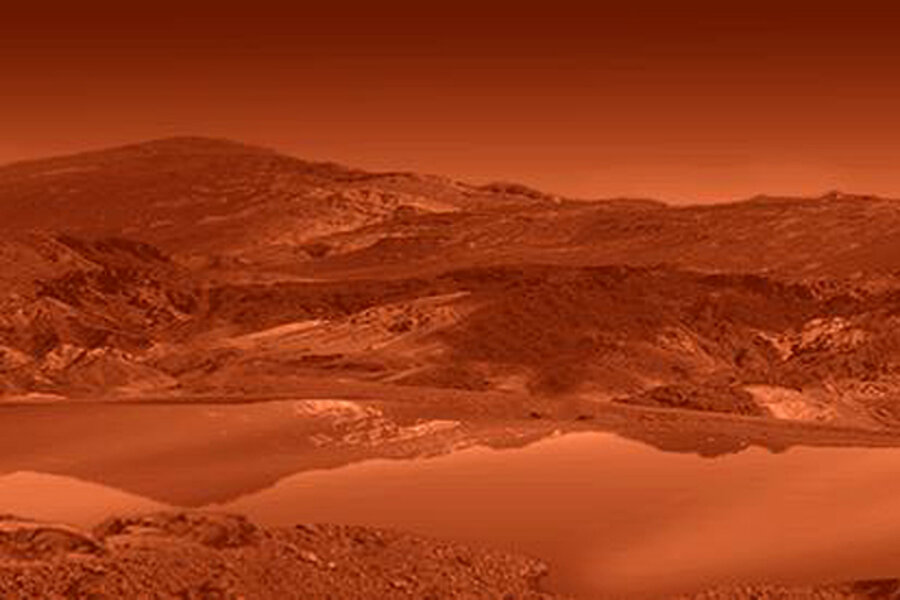

It has an atmosphere – one that is so thick, in fact, that obscures the moon’s surface in a perpetual orange haze. It has rain, rivers, and lakes – making it the only other world in the solar system known to have liquid on its surface. And it’s clouds and seas are thick with hydrocarbons – the building blocks that, when combined, formed life on Earth.

The catch? It’s about minus 300 degrees F on Titan.

At that temperature, water would seem to be useless as means of enabling life. On Titan, it’s frozen as hard as granite and acts like bedrock. Certainly, it could not act as it does on earth – as essential to the formation of DNA.

But with Titan essentially raining the building blocks for life out of the sky, scientists wonder if life might be able to form in ways hitherto unknown.

Frigid chemistry

They do not know how, in such a frigid environment, hydrocarbons could find the energy to combine into the complex structures necessary for life. But Lunine said: “We don’t have a lot of experience with the chemistry that might go on at these temperatures.”

Nor do they know what on Titan might act as a substitute for carbon, which plays a fundamental role in the molecules of living organisms on Earth. But Titan could be a testing ground for the theory that silicon might act as carbon does for other forms of life.

It is, for now, the realm of educated guesswork and intense study of how methane and ethane might act in such an unfamiliar environment.

According to one study, both the composition of the lakes and their depth could be key. Too shallow or with the wrong mix of chemicals, and the lakes could freeze or dry out. Too deep, and important chemicals could sink to the bottom.

But if everything is right “the lake can exist for many years and provide a medium for prebiotic-like chemistry,” Tetsuya Tokano, author of an article in the March 2009 edition of Astrobiology, told Space.com.

Lunine is among a team of scientists working on a potential Titan lander that would splash down in one of the moon's seas and take readings on its chemistry for 16 Earth days. The so-called Titan Mare Explorer has yet to be approved or rejected by NASA.