Loading...

Beyond the buzz: A Monitor film reviewer on the art of curation

What does it take to stand in the torrent of global movie offerings and sift for ones that plumb the human experience, that connect and engage? Our longtime reviewer joined our podcast to explain, and to spin some really great yarns.

The art of film criticism calls for staying open to surprises in a heavy flow of offerings. It also calls for staying grounded.

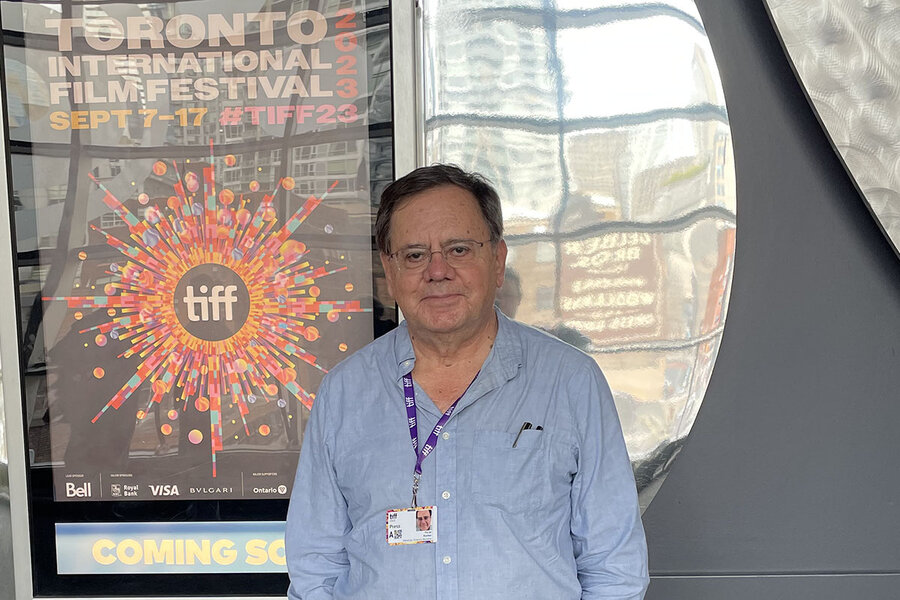

“I try to separate out what I’m seeing from all of the buzz and PR that goes on,” says the Monitor’s Peter Rainer, whose latest test was at the Toronto International Film Festival. “And I think I’m fairly good at that because I’ve been doing this for a long time.”

Peter has been with the Monitor since 2006, after decades of experience – including a Pulitzer-finalist year – elsewhere. He has relished his Monitor role, Peter says on our “Why We Wrote This” podcast.

“For one thing, I can be pretty selective with the Monitor in ways that I often wasn’t with other outlets where you have to cover a lot of movies that are basically there to be reviewed because they’re there,” he says.

It’s not that Peter doesn’t like seeing a good blockbuster, or mixing it up with Quentin Tarantino (listen to learn about that). But his picks from Toronto reflect a sensibility: “In the Rearview” for Peter brought “devastating immediacy” to the war in Ukraine. The documentary “Silver Dollar Road” focused on a Black family that had lost ancestral land in the South to developers.

“I’m always aware of – for want of a better word – the humanistic element in film,” he says. “I think that ultimately, those are the kinds of films that I most respond to.”

Episode transcript

Peter Rainer: The thing that really resonates for me as a film critic is not so much praising a film that everybody loves... But if you can direct an audience to a film that they might not normally know about or even feel that they care about, that, to me, is what it’s all about, ultimately.

Clay Collins: That’s the Monitor’s Peter Rainer.

Peter’s been writing about film for the Monitor since 2006, a three time L. A. Press Club Award winner and the author of the 2013 book “Rainer on Film.” He was a 1998 finalist for the Pulitzer in Criticism while writing for New Times, then a Los Angeles Weekly.

Peter can regularly be heard on the show “Film Week” on the old NPR affiliate KPCC FM. It’s now called LAist. The writer and a co-producer of A&E film biographies of both Sidney Poitier and the Hustons, he sits on film critics societies and associations on both U.S. coasts. And, speaking of sitting, last month at the Toronto International Film Festival, Peter viewed more than 20 films out of several hundred, representing 43 countries, for a Monitor Story.

This is “Why We Wrote This.” I’m Clay Collins, Peter joins us today. Hey, Peter!

Peter Rainer: Hi, Clay.

Collins: You’re a font of great stories about film, not just the written ones, but also anecdotal ones. And it’s kind of hard to know where to start, but let’s take Toronto since you’re just back. What was the atmosphere like your first time back since the pandemic and given the labor strike now apparently resolved that was in full swing then?

Rainer: Well, it was an interesting experience because it’s an international film festival and critics are in from all over the world to see there were about 250, 300 movies potentially to be seen. You know, very diverse content, a lot of films from all over the globe, obviously not in a position to see everything. Even the ones you wanted to see often conflicted with other films at the same time.

So I did see about 20 movies. The mood was kind of, warily, uh... optimistic. The warily part is because the actors and the writers were on strike, so therefore there was virtually no star presence at the festival. No red carpets to speak of, which I personally was not too upset about because I was there to see the movies. So, in that sense, it was kind of a low key festival that focused on the films themselves.

I was happy to see as many films as I did. You get into sort of battle mode if you’re a film critic at a film festival. I take notes. I often can’t read them after I write them down in the dark, but it helps to imprint them on my memory and I try to get a sense of trends.

But again, with hundreds of movies, finding trends is sort of a fool’s errand, because you can just about connect any dot to anything.

Collins: Right. In your report, you mentioned a number of films. “In the Rearview” was one that you said brought the war in Ukraine to life “with devastating immediacy.” What other films were the talkers this year?

Rainer: Yeah, well “In the Rearview” was a great movie, which has yet to find a distributor as we speak. “Anatomy of a Fall” was a big, buzzy movie. It had won the grand prize: the Palme d’Or at Cannes. And that was a terrific film starring Sandra Hüller, who also was in another great movie at the festival called “Zone of Interest,” which is a Holocaust drama. And so those were big movies, and it meant, from my standpoint, you had to get in line an hour ahead of time in order to see them.

There was a three and a half hour Alex Gibney documentary in “Restless Dreams,” a Paul Simon documentary that was quite good and justified its length. There was a documentary about an African American family called “Silver Dollar Road,” they lost their ancestral land in the south and to developers and that was, directed by Raoul Peck, who did “I Am Not Your Negro,” the James Baldwin documentary a couple of years back.

“The Critic,” a wonderful film with Ian McKellen playing a viperish critic in England in the 1930s, a theater critic....

Collins: Must [have been] fun.

Rainer: Yeah, I didn’t take umbrage at the fact that that they made critics out to be poisonous, vengeful.... You know, there was a lot of buzz about a lot of different films. Typically what you had to do was figure out which buzz you wanted to gravitate towards, because of all the conflicts and the overlaps, but those were some of the highlights.

Collins: You just said you couldn’t see it all, and you had to do this choosing. As a film writer, you’re a curator for our audience, really, and when you see a festival’s catalog, how do you go about selecting a set that you want to tell people about?

Rainer: If you just look at the program catalog, every movie is a masterpiece, right? So there are several ways that you can do it. One is that you say, well, I know this actor, I want to see a film with this actor, or this director, or writer, or subject. And you just sort of ... do that. I mean, there are some movies that are kind of obligatory to see anyway, because of advance buzz or whatever, so that’s kind of a given. But then you’re sort of on your own to some extent with the rest of it, and I try in these festivals to look at films that I think Monitor readers and myself would be most interested in long term.

My general rule of thumb: If you’re just a civilian or even a critic in the wild and you go into a festival and you don’t really know what to see, it’s a better bet to try to choose documentaries over fiction films, because documentaries tend to be made by people who have a real passion for the subject. They know they’re not going to make much money from it. There are no movie stars, they had to scrimp and save for years to make this film. And, so, therefore it stands a good chance of being interesting.

Even if the film isn’t particularly well made or whatever, often the subject is really interesting. And ultimately I think that’s more valuable than just a lot of fancy cinematography.

I did try to see documentaries of all kinds at TIFF. One that I wasn’t able to see because it was four hours, but I hope to, is a film about a Michelin-starred, Parisian restaurant by Fred Wiseman, who’s our greatest documentarian. But it was four hours, so it knocked out three other movies each time. I guess, you know, watching somebody slice a garlic for 20 minutes probably would be a bit much.

Collins: Yeah. A chef movie somehow almost sounds worth four hours, though, I don’t know why. It can just be so good. I want to get to how you match to the Monitor audience in particular, but first I want to ask, you’ve been a festival jurist, I think in Venice and elsewhere. How do those experiences compare?

Rainer: Well, it’s very different if you’re on a jury, as opposed to covering the festivals as a critic. Because when you’re on the jury, there are films that are in competition and those are the films that you watch because those are the ones you vote on. There are many, many films, hundreds often in a festival that are not up for competition for one reason or another. It depends on the festival: There can be anywhere from 15 to 40 films that you have to see as a jurist.

And I sit through all films anyway, as a critic. I don’t walk out unless it’s really terrible and I have to see something else at the same time. A lot of critics pop in and out of screenings. I can’t do that.

But as a jurist, there’s like a hall monitor who basically watches you to make sure you don’t leave. So you see all those films and then you have a preliminary vote with the jury and then a final vote. The festival director usually kind of is on the sidelines. They’re not supposed to interfere with your choices, but in my experience they often try to influence the jury in some way. Suddenly one of the jurors mysteriously likes a movie that he or she didn’t like before, and changes the vote, or you get a better hotel room, you get better perks. But the thing as a juror is, it’s the same thing as a critic. You can’t be swayed by any of this, because a lot of this is meant to kind of dazzle you and maybe make you vote a certain way.

Collins: You’ve written for a number of major outlets, so I want to ask you what’s different about doing film criticism for The Christian Science Monitor, besides that documentaries and foreign films are probably often a good bet.

Rainer: For one thing, I can be pretty selective with the Monitor in ways that I often wasn’t with other outlets where you have to cover a lot of movies that are basically there to be reviewed because they’re there, but they’re not especially noteworthy or good. So that’s a real boon. I’m always aware of, for want of a better word, the humanistic element in film. I think that ultimately those are the kinds of films that I most respond to.

I love big blowout movies and some superhero movies, but in making a list of my favorite films, I noticed intuitively that I was picking films by Satyajit Ray, [Vittorio] De Sica, Chaplin, directors like that — Ozu, the great Japanese director … the films were intensely about people and their lives in a very humanistic way. And I think that resonates with Monitor readers as well.

And also, as you mentioned, documentaries: I think it’s important to learn stuff, not in a pedantic or academic way, but to learn other people’s lives and other ways of living through documentary is a great thing. You know, I did several documentaries on Sidney Poitier and the Hustons, and even there, I was entering an entirely different realm.

And, it’s a fascinating experience to do that and to, as a critic and as an audience member, to see other people’s lives and the way they live ... to see it through a non-dramatized periscope is fascinating and important, and one of the things that’s always drawn me to film. I think that’s another thing that resonates with Monitor audiences because there’s a kind of global outreach that the Monitor encompasses that fits very well with that attitude.

Collins: I wonder, besides deciding on what you’re going to review, how are you working with editors these days around themes and ideas, including the Monitor’s sort-of-new values orientation?

Rainer: Generally, I’ll see what’s coming out over the next number of months. It’s not hard and fast because release dates change, particularly with the industry in turmoil. But I get a general sense of what’s out there for the next number of months, and I just sort of figure out with my editor, Kim Campbell, what might be most worthy of being covered.

But I don’t pin anything down until I see the movie. I mean, there are some films, like “Indiana Jones” or whatever, where it’s sort of a given that I’ll be doing it, even if it’s a terrible movie. But a lot of the time, you know, I don’t like to say, “well, I’m going to do this film because blah blah,” and then I see it and it’s terrible. Now, there’s a value in doing terrible movies, too, if there’s something going on in the film that’s worth discussing. And I guess from a consumer standpoint, it’s valuable to tell readers to not waste your money on this movie.

I don’t think specifically in terms of values when I’m doing the review; I just write the review, and, if there’s a value that can be drawn from the review, then that’s what we do. There are many different aspects to a film, and therefore, many different values that can be attached to it, so it’s a kind of shorthand guide to the overall tenor of a movie.

Collins: You mentioned public discourse as kind of one guide to thinking about what to cover, but in entertainment culture, we see these really hyper buzzy phenomena like “Barbenheimer” or the question of whether superhero movies are a scourge, you know, as [Martin] Scorsese and others maintain. The chatter can sometimes become greater than the works themselves. So as a critic, how do you keep yourself moored in your own context-based reality?

Rainer: Yeah, it’s a very difficult thing to do, Clay. I mean, some critics want to know everything about every movie that’s coming out. They read the plot, audience reactions, previews and buzz, advanced reviews, the trades, and all the rest of it. I try to avoid that as much as possible, because ideally I would like to walk into a film not knowing a whole lot about it.

Some people feel differently. You know, I’m not talking even about spoiler alerts, but just ... I want to approach it as freshly as I can, and being in the business that I’m in and also being for the most part in Los Angeles, that’s a tall order, because you’re surrounded by this juggernaut. But I try to separate out what I’m seeing from all of the buzz and PR that goes on, and I think I’m fairly good at that because I’ve been doing this for a long time, and I know hype when I hear it, and, you know, I just can sort of separate it out.

But in the case of “Barbenheimer,” that was a very interesting phenomenon. Because I saw “Barbie” at a press screening several weeks before it opened, and you know, I had fun with it. I thought it got a little preachy, and I thought the preachiness aspect to it was going to undercut its commercial potential.

I didn’t think it was going to be a smash hit, so that’s why I’m not a studio executive. [Laughs.]

And “Oppenheimer,” I also saw several weeks before it opened. Chris Nolan, who directed “Oppenheimer,” was initially really annoyed that his film was being lumped in with “Barbie” and this whole “Barbenheimer” phenomenon. But I guess after he found out that it was gonna boost the box office, he quieted down.

Barbie’s now made like a billion and a half dollars, and “Oppenheimer” is closing in on a billion. I would like to think that the phenomenon of people seeing the film the same day and dressing up in pink and all of this signals a return to the theatrical experience for a lot of people who’ve stayed away from seeing movies in theaters for years. But I think it may just be a kind of bizarre one-off – that somehow, these films were so disparate that there was a kind of synergy there that nobody could have predicted. It doesn’t necessarily mean that, “oh, I love ‘Oppenheimer,’ now I’m going to start seeing movies every week.”

I think I’m old school in that ideally I would love to see as many films as I can, the way they were meant to be seen: on a big screen.

There are a lot of documentaries and smaller films where it doesn’t really matter that much, but for the most part – and I think most filmmakers would agree with me – they want their films to be seen in a communal setting on a big screen.I think hopefully that’s coming back, to some degree.

I don’t think we’ll ever come back to where it was, pre-pandemic. But I think that the joy of being in a crowded theater – masked – and seeing something that really elates you, and feeling that shared experience on this larger than life imagery is unmatchable.

Collins: Peter, violence in films is something that you’ve decried, when it’s gratuitous or glorified. And you’ve had an interesting relationship with Quentin Tarantino, who’s an apparent fan of yours, even though you haven’t … [laughs] ... you haven’t been anything approaching a fanboy. Can you tell us about the encounter you had around the time “Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood” came out?

Rainer: Yeah. That was very interesting. I was, at the time, a member of the New York Film Critics Association – as well as LA – and we had an annual awards dinner and he was given the award for best screenplay for “Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood.” So I’m there with my date and my two nephews and we’re having a wonderful Chinese meal, a star-studded room, lots of other famous filmmakers and critics and Tarantino accepts the award and starts thanking people and he says he’s always grew up reading critics, and then he says...

“Peter Rainer, film critic for The Christian Science Monitor, you’ve never given me an (expletive deleted) good review in (expletive deleted) 30 years!” Uh, so, you know, I dropped my chopsticks and, you know…whoa! And I looked over to my nephews, and they said, “cool!” So…

Collins: [Laughs.]

Rainer: Then he went on to say, “you know, I grew up reading you. I worked in a video store. I saved your reviews – I still have your (expletive deleted) reviews in my office.”

I didn’t know how to take it. I mean, it’s a weird sort of backhanded compliment. Um, I [had] never met him. So afterwards, everyone said, “well, you’ve got to go over and say hello to Quentin,” and I said, “well, really? I don’t want to get, you know, into punching.”

But I did, and, you know, I said, “look, it’s... It’s not actually true that I’ve never liked any of your films, I think you’re very talented, I love ‘Jackie Brown,’ and I think you deserve a lot of credit for resuscitating the careers of John Travolta, Pam Grier, and Robert Forster, and this idea that you’re going to stop making movies after your next one and retire after 10 would be a loss to film.”

I didn’t get into the violence aspect with him because I just didn’t want to get into it with him, but he accepted it sort of graciously. You know, his wife was there giving him the side eye, but that was my encounter with Quentin. The problem I have with his movies and with violence on film in general, it’s not so much the depiction of violence that I don’t care for; it’s the lack of consequence to the violence.

I’m not talking about big, blow-up superhero movies, but films where “real” people supposedly are getting shot, killed, maimed, etc., and, you know it’s like a bunch of schmooze, and I felt that that was the case with a lot of Tarantino’s movies, that it’s there as a kind of theater. It doesn’t really have any sense of human consequence to the violence, and That’s what I object to.

Collins: It’s a good story, and as you said the other day when we spoke, unless you’re a hermit, you end up in close proximity to people you’ve either praised or disparaged, and there you have it. [Laughs.]

Rainer: Yeah, well, it’s true. I mean the thing is if you’re a film critic, particularly in Hollywood or to some extent in New York, you’re going to find yourself in situations where you are in close proximity with filmmakers and actors. My feeling is, you know, look, if there’s an actor or director who you really admire their work, and they’re at the other end of the room or something, it’s only human to want to reach out and say something, you know?

The difficulty is when you don’t like one of their movies, and then you find out who your real friends are – that’s happened, too. You know, you just have to say, “well, I’m going to be true to my values, and if they don’t like it, then that’s it.”

Still, you know, you try to avoid certain situations. My dad went to college with Glenn Close’s father and he said, “well, if you ever run into her out there, you should say hello to her dad for me.”

So I said, “OK, fine, never gonna happen.” And of course, about two months later, I’m in this function and there’s Glenn Close, who I’d given … you know, I thought, OK reviews to, but I made the mistake of going over and introducing myself and extending my hand, you know, doing all the wrong things. And this is around the time of “Fatal Attraction.” And she gives me this, you know, sort of basilisk’s look and says, “I don’t think I like you.”

So, you know, there’s that too.

Collins: She had just boiled the rabbit, to be fair. So maybe just a holdover.

Rainer: [laughs] Yeah.

Collins: Peter, we also spoke off mic about how much you like to tell people about movies they should see, films that might even change their lives. And you said you never look down on people with gaps in their film knowledge.

So how did film capture you and what do you want people to know about the greatness of film?

Rainer: Well, I loved movies from as early as I can remember anything. I grew up in New York, in the suburbs, so I would go to a lot of the art houses and see great movies in revival or on [WITI-TV’s] “The Late, Late Show,” and in college I was the film critic for my college newspaper. I always had this love for movies and I loved comic books and I realized it’s because the frames of the comic book are like storyboards, they sort of show you the frame by frame action. It was very interesting.

The thing that really resonates for me as a film critic is not so much praising a film that everybody loves… I mean, that’s great. I love “The Godfather,” I love a lot of very popular movies – “Jaws” – but if you can direct an audience to a film that they might not normally know about or even feel that they care about, that to me, is what it’s all about, ultimately.

When you review a movie and somebody says, “you know... I saw this film that I wasn’t gonna see, but, I sort of trust what you have to say even when I don’t agree. And I went to see it and I loved it.”

An example of this was earlier in the year: it was a film called “Past Lives,” by a Korean-Canadian director. It’s a wonderful movie, and it’s gotten a lot of momentum since then, basically. From critics like me and [through] word of mouth, you know, audiences have started to see it... that’s incredibly gratifying.

When I’ve taught film classes, I realized that a lot of the young people who are seeing films now don’t have a knowledge of film going back five or six years. If you mentioned Marlon Brando or Dustin Hoffman, you get a blank look. And initially I felt, “Oh, gee, that’s terrible.” I mean, you’re trying to make this your life. And if you were a grad student in American literature and you’d never read Melville or Hawthorne or Henry James, you know, what does that say? But my attitude now is, “well, wow, you have a lot to look forward to. I envy you.”

And also, I like letting people in on what’s great. And from older movies, give them a sense of what’s going on now in movies. Because if you only go by what’s out there now in film, there are certainly great films. But there’s this backlog of hundreds and hundreds of great movies that can literally change your life for the better. They can transform you and open your eyes to what art can be, what life can be, what the human experience can be in ways that are incredibly fulfilling.

But I think to be able to really open people’s eyes to movies in a way that maybe they wouldn’t see normally on their own, to say I didn’t see that in this film, now I do, I understand what he’s saying, I understand more of what’s going on here. I think that’s the critic’s function.

Collins: Thank you, Peter, for talking today, for being very much up to speed and for being a guide. For Monitor readers on an important part of the cultural landscape.

Rainer: Thanks, Clay.

Collins: Thanks for listening. You can find more, including our show notes with links to Peter’s Toronto story and more of his work at CSMonitor.com/WhyWeWroteThis. This episode was hosted by me, Clay Collins, produced by Mackenzie Farkus and Jingnan Peng. Tim Malone and Alyssa Britton were our sound engineers, with original music by Noel Flatt. Produced by the Christian Science Monitor. Copyright 2023.