Loading...

Episode 9: The Role of War

War… what is it good for? Turns out, perhaps peace. While we continue to fight long and expensive wars around the world, they are much less fatal than in the past. But with how much war has changed through the decades, do civilians really understand its role?

Episode transcript

SAMANTHA LAINE PERFAS: The ongoing war in Syria. The never ending Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Terrorist bombings in Afghanistan. ISIS attacks in Europe and Canada. Civil war in Libya and Yemen. The United States alone has 450,000 troops stationed overseas today, often in many of these hot spots between terrorism and wars. The world certainly appears more violent than ever. Or is it? The reality is there are fewer armed conflicts worldwide than at any point in human history. But many people may not feel that way. And that's a perception gap.

I'm Samantha Laine Perfas and this is Perception Gaps by The Christian Science Monitor.

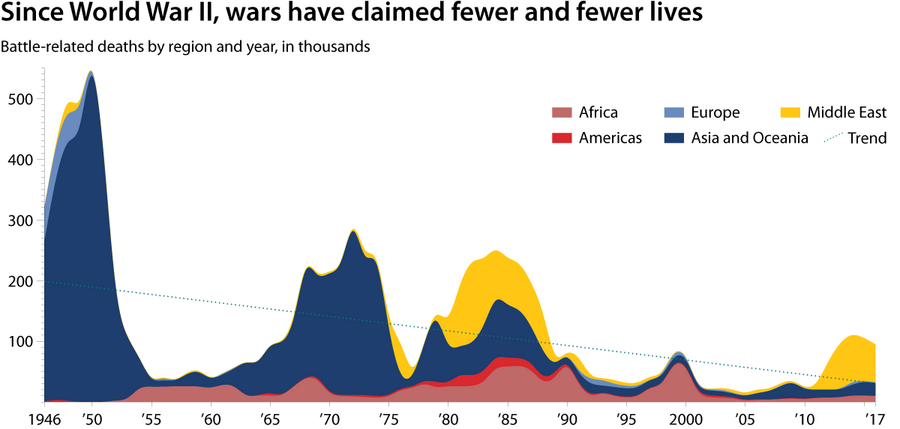

Not only are there fewer wars and fewer state conflicts and fewer terrorist attacks, but when there are wars, there are also fewer deaths. Max Roser of the publication Our World and Data presents what he calls an empirical perspective on war and peace. His research shows that contrary to popular belief, we were much more violent in the past. And since 1945 the absolute number of war deaths has been on the decline. As he puts it, although wars are still fought, the world is now more peaceful than ever. We'll look at some of the reasons why wars are less deadly in today's episode. We'll also take a closer look at gaps in our perception of war. The truth? Most of us have no idea what war looks like. Pew Research Center studied this so-called "military civilian gap" and they found that 84 percent of modern era veterans say the American public has little to no understanding of military life. And 71 percent of the American public agrees. Why do we have such misperceptions when it comes to war? Not only about its prevalence, but also what's at stake for those who fight them.

JOSHUA GOLDSTEIN: Well there's always going to be wars somewhere and it's certainly not zero now. And reporters will go to where the wars are and so they'll always be on the front page as bloody as ever, and as horrible as ever.

PERFAS: Joshua Goldstein is an emeritus professor of international relations at American University in Washington DC. In 2011, he wrote a book called "Winning the War on War," which looks at wars declining nature through time. Here's our conversation.

PERFAS: What is the status of war around the world right now?

GOLDSTEIN: War is in a low period in the last 30 years since the Cold War ended. And it had a spike upward with the war in Syria, which is now drifting back downward again. So in historical context we're at a low point in war.

PERFAS: Why does it feel like wars are a lot worse today if they're actually not?

GOLDSTEIN: If you're in the middle of a war right now today, it's as horrible as any war in history. But the difference is, and this is what the reporting doesn't get, fewer people are in the middle of wars right now. Whole regions of the world that used to have multiple wars like South America, Central America, now are at peace. And whole categories of war that used to be just devastating to large numbers of people just aren't happening anymore.

PERFAS: Do you think that war is less fatal now than it was in the past?

GOLDSTEIN: The big thing in this decrease of war fatalities has been the wars between large, national, regular uniformed armies. Those were the big wars that took the biggest toll in the past. India versus Pakistan. Iran versus Iraq. And those wars used to happen all the time, usually several of them going on at once in the world. But nowadays they've almost completely stopped. The last one was the several weeks when the US and the Iraqi army were fighting 15 years ago. And so eliminating that whole category, national army, one on the other, each one armed with tanks, airplanes, missiles, submarines, and all that stuff, they're not fighting each other anymore. So the character of war is changing and it's getting smaller scale in that way. And that's the biggest factor going on. Now, I think that also UN peacekeeping has been a factor in the civil wars because peacekeepers have been able to come in when there's some effort to get a cease fire and to end the war. The data show that having peacekeepers there really helps because most ceasefires break down, most wars sputter on and off for a long time, and a lot of people die. But with UN peacekeepers, it's much more feasible to end the war and keep it ended. And then underlying it is the rise of economic development and prosperity in the world. Poverty breeds wars. And again, kind of below the radar where people are aware of it, there's been a big improvement in poverty in the world. And I think that's been an underlying factor of fewer wars.

PERFAS: Do we think that war is more violent today in part because of the way the media covers it? Is that different than in past decades?

GOLDSTEIN: Yeah absolutely, because in past decades large numbers of people died horrible deaths in war and the Western public never heard about it. But now it's much more likely that someone will have a cell phone, someone will take video, the video will go to global news organizations and everyone will hear about it. So before Vietnam, war was really distant and did not make it back to the home front and when people came home they didn't talk about it. And Vietnam was the first American war that was on our TV screens in the living room. But now it's gone way beyond that, even relatively small wars in distant parts of the world come right into our social media every day.

PERFAS: Joshua and I talked for a while about how wars are covered nowadays. I brought up the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and how they are the longest and most expensive wars in US history. One of the latest calculations shows that so far we've spent $5.6 trillion on Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. So if we're spending this much money, and the wars last so much longer, it's no wonder it feels like war fatalities and violence have also increased. It feels counterintuitive to think otherwise. But that's Joshua's point. There's a misperception there.

GOLDSTEIN: There's a disjuncture between how violent wars are and how much they cost. Levels of violence have gone down dramatically in recent decades but the levels of military spending really haven't. Most of the military spending goes to maintaining large military forces and they're about as large as they've ever been in the world. The exception of nuclear weapons which are now smaller, but the number of people killed is a lot smaller. So yeah these wars have been much more expensive than you would expect or the actual physical size of them.

PERFAS: You mentioned nuclear warfare a little bit, and I just wonder, there's a lot of talk about who's got their finger on the button or finger on the trigger. Do you think that nuclear warfare changes the perspective or conversation when we think about war?

GOLDSTEIN: Nuclear war is completely terrifying and is something to be worried about, but there's always something to worry about. And nuclear weapons themselves have decreased since the 1980s by three quarters. So we're down at about a quarter the level that we were then because of the United States and the Soviet Union destroying and getting rid of our weapons. And in fact we've been, for a couple of decades, burning nuclear warheads from the Soviet Union, the old ones, in our nuclear reactors in the US. Powering light bulbs around the United States with them. People don't know this and because nuclear war is so terrifying and because there's still plenty of nuclear weapons that completely ruin the world, they don't realize that actually the numbers are going in the right direction. We have a lot more work to do on that.

PERFAS: For the wars that do exist and the wars that are currently happening around the world... is there hope? Or where do you see hope for peace, based on this trajectory that the numbers are sort of going in the right direction?

GOLDSTEIN: The numbers are hopeful but I would never put my hope just in numbers, somebody is going to argue about how you're counting things. But the big things that I think can't be argued with are the fact that the national armies aren't fighting each other and haven't anywhere for 15 years. And along with that whole category, like tank battles and naval battles, just haven't been happening. That's a big cause for hope. And then we haven't talked about this but geographically the area of the world affected by war is shrinking. I mentioned Latin America but also the Balkans and Southern Africa, South East Asia, places that used to have a lot of wars and now are completely at peace, or almost completely at peace. That's a cause for hope and so the remaining wars in the world are now limited to an arc from Central Africa up through the Middle East and over to Afghanistan, which is you know it's a considerable area but it's about one sixth of the world that lives there. So five sixths of the world lives in places that are not having wars and haven't for a while. And I think that's quite hopeful.

PERFAS: Joshua said another area that brings him hope is the UN peacekeeping. He said 100,000 peacekeepers are deployed in the world. And data show that their presence works and they are generally effective in keeping the peace. Now I'm going to let our next guest introduce himself because it's a mouthful and I simply couldn't do him justice.

ADRIAN LEWIS: OK. Yeah. No I'm I'm Adrian Lewis. I'm a professor at the University of Kansas. I'm also a retired soldier. I spent 20 years the United States Army, I served as an enlisted man, a sergeant. Then an officer. I served with the 9th Infantry Division. My primary MOS was infantry and I also served with 2nd Ranger battalion up at Fort Lewis in Washington.

PERFAS: So Adrian is a retired soldier, and now he studies war as an academic. I asked how has he seen war changed through the years and what has made it less violent?

LEWIS: In World War 2, 70 million people were killed at the end of the war. We developed nuclear capabilities, which we used on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and then, what we do is enter the nuclear age. When the Korean War started, we had the potential to stop the Chinese using nuclear weapons. But the Truman administration decided not to do that. In other words, we entered the period that we call artificial limited war. The word "artificial" is important, because we can always remove it. In other words, we might go back to total war. We live in an era where the nuclear potential still exists. But we, we put artificial restraints on the conduct of war. So when you take a look at the Korean War, what we did was we put artificial restraints on it. Wasn't just us, Stalin, Mao Tse-Tung, also put restraints on the conduct of the war. Everybody had fresh in mind the 70 million people, particularly the Russians who lost 30 million people, everybody had that fresh in mind. So we were trying to step back from the brink and we fought limited wars in Korea. We fought another limited war in Vietnam. Both of those at various times had the potential to escalate. So we've been in this era that we call artificial limited war. And we are still in it today because these nuclear arsenals still exist.

PERFAS: So it almost sounds like because we all know that we have the technological capability, it's actually keeping us in check because we don't want a repeat sort of that massive carnage that's happened in the past.

LEWIS: That's right. I think that's accurate. We have the capability to destroy a city the size of Chicago. So with such capabilities, yeah we need to be very careful. The big danger out there is smaller nations or terrorist groups getting nuclear weapons. We try very hard to not have the proliferation of these weapons around the planet because the more people that have them, the greater the chance that something, something will happen and they will be used again.

PERFAS: A little side note: his point about proliferation is why some people are concerned that the US is withdrawing from the Reagan era arms control treaty with Russia. Even though we have reduced nuclear weapons, the prospect of reversing that trend is what has some people scared. Let's shift gears here. I asked Adrian about the civilian military gap that I mentioned at the beginning of the episode. Most Americans don't really know what war is like or what it means to be in the military. Why is that?

LEWIS: We know we know that is. The armed forces are concerned about this issue. Only one percent of the American people serve in the armed forces of the United States. One percent. When you think about that, the vast majority of Americans have no association with the armed forces. None whatsoever. And then when you add to that, that you know, in the Pentagon they talk about a family owned and operated business. Sixty percent of the people in the US Army and the other services are the sons and daughters of other servicemen. So when you actually take a look at it, then the vast majority of Americans have no idea what their armed forces do. They never see them. They don't interact with them. So yeah yeah, they are a separate culture. They are physically separated and the American people pay for it, but they have very little idea what their money is going for.

PERFAS: What are some of the biggest things that you think civilians misunderstand or are just simply unaware of when it comes to war or being in the armed forces?

LEWIS: I would say the biggest thing is they don't understand what we do around the world. We provide security on the planet. Completely, from one end of it to the other end of these things. At the end of WWII we created these mutual security agreements such as NATO, and we're the largest player in those agreements so we provide security around the planet, which is a good thing for humanity on planet Earth. You know, some of the things people worry about is dismantling the security systems that the United States put in place at the end of WWII. They have worked. They have worked. You know you can't find 50 years of peace in Europe before the period that we created NATO. So these systems have worked. We want to make them stronger. We don't want to weaken them.

PERFAS: So we often hear a lot you know, people saying I support the armed forces. I support the military. What does that actually mean, and how how can we do that in sort of a practical way?

LEWIS: I remember... I can remember the days after the Vietnam wars. When we were not liked. When the US Army, when we were told to not leave post in uniform, when we were told to grow our hair long so that we fit into civilian society. I can remember a very different time and that didn't turn around until the Reagan administration and then really turn around until after Operation Desert Storm in Iraq. And then we had the parade welcoming the soldiers home from Iraq, and then they had a parade to welcome the Vietnam veterans home, who had never been welcomed home. So from my perspective, watching this transition from being greatly disliked and disrespected after the Vietnam period to where we are right now, that's a huge change. It's an important change. And so I like hearing that. I'm never gonna argue with hearing people say, gee, I support the armed forces of the United States. People don't realize all the things that we do in various parts of the world. Small forces doing little things in some place like Africa can make a big difference. Let me give you an example. If I give some people in a smaller country in Africa let's say, if I give them weapons, then they tend to want to prey upon the people. They now have the means to do that. But if the United States spends a few bucks, if they give them weapons, then put them in a uniform, then give them a barracks, and then give them some training and talk to them and teach them about professionalism, then they can learn that their job is to protect the people, not to prey upon the people. Then they can become a national asset as opposed to a national problem. It's a small investment for the United States and it can make a huge huge difference.

ELLIOT ACKERMAN: I think there is a civil military divide that exists today and that's because we have an all volunteer military. So it has become increasingly less common experience among larger swaths of society.

PERFAS: Elliot Ackerman is a novelist whose books have all related to conflict in the Middle East and Afghanistan. He is also a former Marine who served five tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, where he received the Silver Star, the Bronze Star for Valor, and the Purple Heart. I asked them to share a bit of this story and why he decided to enter the military.

ACKERMAN: I was an a officer, so I wanted a job when I got out of college. Whether I was good at my job or bad at my job really mattered, and one thing the military gives you is a lot of responsibility at a young age. I wanted to do something, wanted to give back to my country and serve my country and I was also probably one of those kids who never stopped playing with his G.I. Joes and I just had this innate interest in the military that never subsided.

PERFAS: Did you feel like it met your expectations or did it surprise you? What you thought it was going to be like and what it was when you entered?

ACKERMAN: I think it exceeded my expectations in so much as I came in to the military in 1998, meaning I started the ROTC program I was in that would take me through college. And so while I was a ROTC student in college, September 11th happened and then I graduated right when the Iraq war was beginning. So I say it exceeded my expectations, because I came in thinking, you know, maybe I'll do a deployment and who knows, if I'm lucky, maybe we'll get to do something real in the world. But chances are I'll just be a peacetime deployment. And I wound up going in and fighting in pretty significant actions in both Iraq and Afghanistan. But the whole world changed in the time I was in the military.

PERFAS: What did you learn in Iraq or Afghanistan about the nature of war that you feel like most Americans find surprising or that you yourself found surprising?

ACKERMAN: I think what most people who've never experienced war might find surprising is how boring war is. How actually nothing much is happening most of the time. You know, if you watch movies like Platoon or Full Metal Jacket or Apocalypse Now, you would think that every time you walked outside the wire, meaning your base, all hell was breaking loose. People were shooting at you, things were blowing up. And I would say those films, if you were to take a seven month deployment for a bunch of Marines and were to distill everything that happens over seven months, it would probably be one of those films. But it takes seven months for all of that stuff to happen. So I think that is something most people don't understand about war. And frankly, when you're in the middle of a firefight and you're being shot at, how most of the time you're just trying to figure out where they're shooting at you from. You can't see each other most of the time, that it's actually often just this huge game of hide and seek and the confusion that comes with that. I would say you know, most of the time, being at war is you're sitting around, you're going about your business, you're doing your job, and then you know, an IED blows up, and you're in an ambush, and it's you know an hour or two. It's very intense and someone's been hurt and you have to deal with that. Have to deal with what's going on, getting to safety and dealing with a threat you're experiencing and that happens. And then two weeks pass and nothing happens and then something else happens. So sort of these these strings of events. And then you can also have experiences, I fought in the 2004 Fallujah battle and that was a very high intensity experience and different than I think what many people experience in these wars. That was a set piece battle but there are very few of those.

PERFAS: Do you think that Americans would benefit from having a better understanding of war, and why or why not?

ACKERMAN: I think Americans would benefit from having a more direct tie with their military because it would make them aware of what it means to go to war. And I think the more and more our military becomes a separate cast, a separate warrior cast in US society, it means that most Americans don't understand the significance of what it means to decide whether or not to remain at peace or to go to war, or what it means and we send our troops overseas. And I think it also accentuates the gap that exists in terms of how Americans perceive themselves and how Americans are perceived abroad, because so often we don't really understand what's being done in our names abroad.

PERFAS: And what do you think could sort of help bridge that gap?

ACKERMAN: I think I think a draft. I'm very much for a draft, some type of national public service that's linked to the military. I think we have an all volunteer force and we want to retain the professionalism of that force. But I think that having some percentage of that force, 5 percent, 10 percent, that's drafted would make it so every American has skin in the game, even though they, or their son or daughter might not be drafted. They know that that's a possibility.

PERFAS: I feel like when you hear the word draft it's a bad word, and it has a lot of negative connotations and I feel like people even like start to panic or get anxious or be like, no, we absolutely couldn't do that. Is some of that just a misunderstanding of what war is like?

ACKERMAN: Well, I think people panic because they think, well if there's a draft then I will be forced to go to war. I think it's actually some of the difference. If there is a draft, we'll be a country that's more likely to remain at peace. Because it will make it far more difficult for us to go to war. And right now we're living in a society where it's become too easy for us to go to war. It's become too easy to do what we're doing right now, which is we've been waging wars for 17 years. We've done it with an all volunteer military. And Americans haven't had to pay for it because we've done it through deficit spending. Is that the type of country we want to live in? And is that representative of our values?

PERFAS: What have you noticed to be some of the consequences or aftermath of war for veterans when they come home? You know, you hear about PTSD a lot. Veterans coming back totally shell shocked or just unable to integrate. Do you feel like that's the reality?

ACKERMAN: When you talk about PTSD, I think there is a type of PTSD that's the very acute PTSD that we think about with you know, flashbacks, nightmares, and that's a real thing. Let's table that for just a second. Then there's this sort of another type of PTSD which I think in some ways is more insidious and affects a lot more veterans. And allow me to explain. I think for any person to be happy, anyone, you have to have a sense of purpose in your life. And to give you a very simple example, you know there's a man, a man works a job and he puts food on his table, his children go to school, they have a better life than him, that's his sense of purpose. You know, I think you would say that, you know purpose is like the drug that it induces happiness in our lives. So when you go to war at 19 or 20 years old, your experience is you know, you're sent to let's say a remote Afghan hilltop, or a hellhole in Iraq, and you have a relative, you'll have a relatively, your sense of purpose is a relatively clear job, which is to tactically hold the hill, make this square block safe. And you'll be doing it with people who have probably become some of your very best friends. That's actually a very, it's a very intense sense of purpose. I think you wind up developing almost a dysfunctional relationship with purpose. You do it for a few years and you maybe do a few deployments, but then you decide the war's over, you come home. And now you have to, to be happy, you have to repurpose yourself. So you look around and you see what's out there and maybe it's you're going to go back to college, or go get a job at Home Depot, or sell real estate, or something like that. And there's this depression. I don't think that's specific to the veteran. I think you see this with professional athletes. You see this with artists who achieve very early great success. And I think anyone who is ascended to the mountain top has to reckon with the descent. And I think that is an affliction and something veterans struggle with, that often gets wrapped up into PTSD. We can call it PTSD or not, but it's a real issue, that how do you repurpose yourself when you come home?

PERFAS: I thought Elliot's insight into the soldier's experience of coming home was really... eye opening. I tried to envision my own life and I asked myself: how would I feel if I felt that nothing I did could live up to the experiences I had as a 19 year old? How would I find my own sense of purpose? How would I not feel lost? Thinking about the veteran experience in this way could help as we think about how to better support our troops when they come home. Before we close I wanted to return to my conversation with Elliot. He talked about what it feels like to come home and reunite with friends and loved ones. Those interactions are key and it's important for us to think about how we interact with our veterans when they come home.

ACKERMAN: I've had a lot of people say to me, I can never imagine what it was like over there. I can never imagine you've been in combat. I can't imagine what that would be like. And when people usually say that to me I think they're trying they're trying to be nice. They're trying to be deferential, but it's actually a very disempowering thing to hear. And I say it's disempowering because I remember who I was before I went to the war. And if I've had some experience that someone at home can never imagine, it means I've been, not only I've been changed, but I've been changed in a way that's inaccessible to the people who knew me before. So there's a part of me that's inaccessible. And if that change is taking place, in some respects it means I never get to go back to being the person I was before. It means I never get to come home. And I tell people and I believe this, it is like you can imagine it. Sure you can. You know like, have you ever lost someone that you loved? Have you ever had something violent happen, have you ever been in a car accident? You know, or been really scared? You can imagine it. And if you can't imagine, you make those effort to imagine, it's realized that my experience is probably not that different than your experience. The specifics might be different because its war but the loss and the feelings of fear and what you have to overcome are not that different. And then I actually get to come home in a way that I won't if I'm just cut off, and people don't engage with that experience. I think it's really important for all of us to engage.

PERFAS: Thanks for listening to this episode. And I want to use this moment to say thank you to those who serve in the armed forces. While we may not understand the depth and complexities of what you do, we hope you know that you are appreciated and valued. And we hope you'll trust us enough to share your experiences so we can better understand and support you.

We're getting close to the end of our series. So if you haven't already please send us a note let us know your thoughts and whether or not you think we should continue. You can email me at podcast@csmonitor.com.

I want to give a quick thanks to everyone who helped to make this episode happen. My producer Dave Scott; our studio engineers Morgan Anderson, Ian Blaquiere, Tori Silver, Jeff Turton, and Tim Malone; original sound design by Noel Flatt and Morgan Anderson; and a special thanks to all my volunteer editors: Mark Sappenfield, Amelia Newcomb, Mark Trumbull, Andy Bickerton, Greg Fitzgerald, and Eoin O'Carroll.

And I'm Samantha Laine Perfas. Thanks for listening to Perception Gaps.

COPYRIGHT: This podcast was produced by The Christian Science Monitor. Copyright 2018.