Loading...

Episode 8: The Drug Epidemic

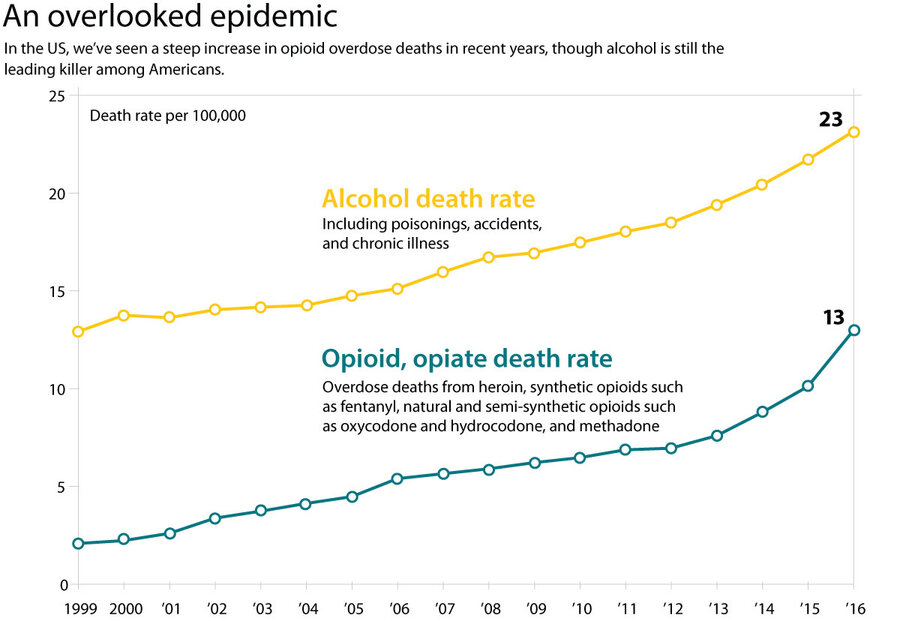

The opioid epidemic is a frequent headline contender, and was recently declared a national public health emergency. But did you know that there’s another substance that regularly kills twice as many people per year?

Episode transcript

MEDIA MONTAGE: More Americans are dying because of drugs than ever. The deadliest drug crisis in American history. This country's recent surge in opioid addiction. President Trump declaring war on the nation's opioid crisis. I am directing all executive agencies to use every appropriate emergency authority to fight the opioid crisis.

SAMANTHA LAINE PERFAS: You've probably heard about the opioid epidemic. For good reason. The rise in overdoses has increased at a rapid rate. But what if I told you that opioids are not responsible for the most substance use deaths in the United States? Yes, opioids are a big problem but they're not the drug responsible for killing the most Americans every year. And that's a perception gap.

I'm Samantha Laine Perfas and this is Perception Gaps by The Christian Science Monitor.

We've seen a steep increase in opioid overdose deaths over the past few decades. It was even declared a national public health emergency, with a little over 42,000 total deaths caused by opioids in 2016. But if you had to guess what drug is killing the most Americans, over double the number of deaths caused by opioids? Alcohol. Not heroin, cocaine, prescription drugs, or meth. Alcohol. 88,000 deaths per year. In this episode, we'll talk about opioids, but more importantly, we're going to talk about the US's overall drug epidemic and what's driving people to use substances in the first place.

SCOTT FORMICA: This is a really interesting area because I know, I think you're almost looking at two sides of the same coin when you're talking about alcohol and when you're talking about opioids. All of these different risk behaviors and all of these different factors are related.

PERFAS: Scott Formica is a senior research scientist at a company called Social Science Research and Evaluation. Having been in the field for 20 years, he has a broad perspective of how we got to where we are now.

PERFAS: So this might be a silly question, but I guess, when we talk about opioids and you hear it a lot in the news, what is it that makes it an epidemic?

FORMICA: One statistic or the one indicator that people tend to focus in on are the drug-related overdose fatalities. And you know the soundbyte that we have we often heard was that the number of drug overdose deaths has increased to the point where it exceeds the number of motor vehicle fatalities.

PERFAS: I was actually surprised to learn that alcohol is responsible for many more deaths each year than opiates. You know, it's the third leading cause of preventable death in the US. So why do you think the conversation is so focused on opioids, if there's another substance that's arguably causing much more damage than opioids?

FORMICA: The last estimate I saw was that on an annual basis there are roughly 88,000 deaths that can be attributed back to alcohol. And when you look at drug overdose deaths, one of the concerning things is there's been a dramatic rise in drug overdose deaths, many of which, again I want to say around two thirds of the most recent estimates I've seen, are are attributable to drug related opioid deaths.

PERFAS: I want to take a moment to clarify something here that I found confusing while doing the research for this episode. When you get the overdose numbers from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, there are various ways the information is presented. The number that is used a lot is that there were 72,000 overdose deaths in 2017. It's important to note is that 1) this number is provisional. It's possible it's going to change. And 2) this number is all drug overdose deaths not just opioids. Opioid overdoses, as Scott said, account for about two thirds of overdose deaths. And looking at the definitive 2016 numbers, it puts the total fatalities caused by opioids at around 42,000. This is a big number, don't get me wrong. But in many of the articles I read, I was finding the 72,000 number quoted but then only talked about in terms of the opioid epidemic when in fact it's all overdoses. It's just an interesting point that I want to underline. Back to our conversation. So the number of people dying from overdoses is increasing, which is a great cause for concern. But why doesn't alcohol receive the same amount of attention?

FORMICA: When we're looking at something like alcohol or we're looking at tobacco, people are familiar with these substances, and people are familiar with, you know, with the potential consequences. You know, people know about cancer, they know about binge drinking. When we get in to looking at opioids, there's still a lot of members of the public who aren't as aware or as familiar with prescription pain medication, with heroin. It's not something I know about. It's not something that, you know, I may have seen before. So a lot of the media that goes out and even from the public health side is intentional because it's awareness raising. And I think that that's appropriate for you know, kind of where we are in the trajectory of this.

PERFAS: Yeah. I mean, I think like, I don't have a lot of information about opioids, whereas alcohol, you see it everywhere. One thing I'm noticing is it's such a fine line between educating people and scaring people and stigmatizing people.

FORMICA: Yes absolutely. I agree with everything you just said and responsible messaging is something that a lot of folks have really taken a hard look at. There are many parallels actually to suicide prevention, and the suicide prevention folks have been working on this for years and years around you know, responsible messaging. How do you work with schools and other agencies and departments in the community, how do you work with the media to make sure that you know that the message is getting out in a responsible and safe manner? Yeah that's something we still need to work on and it's probably responsible as you said for causing a little bit more fear than than is warranted in some cases. Certainly not in every case.

PERFAS: Where do you see the most hope in the future, whether it's changing the conversation or even if it's just in addressing either the opioid epidemic or just substance misuse in general?

FORMICA: I think there are a couple of positive signs. So from a more societal perspective, I think we're seeing evidence that prevention is working and we're seeing evidence that in general, that the trends for almost everything, you know is kind of coming down with regard to use. So you know I am hopeful. Yeah I mean there there are glimmers of light. And you know I don't want to overstate it, but from what I've seen most recently, the preliminary estimates are that for the first time in many many years the opiate overdose fatality down in Massachusetts from 2016 to 2017, I think at this point. And the final numbers I don't believe are in yet. But there is a 4 percent decrease. But it may go up again. Yeah. So I don't want to overstate it, but I think it's nice to see, you know, for once even if it is limited that the numbers have come down a little bit.

MICHAEL BOTTICELLI: Addiction is a chronic disorder that requires treatment. It doesn't require harsh punishment or punitive approaches. If you look at public opinion polling, we still have a significant gap between how many people perceive people with substance use disorders and how they're treated. I think that conversation is beginning to change, largely it's precipitated by the opioid epidemic.

PERFAS: Michael Botticelli is the executive director for the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center. He also served as the director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy during the Obama administration. The person in this position is often nicknamed the drug czar. Michael himself is in recovery, which gives him an insightful and unique perspective regarding substance use. Here's our conversation.

PERFAS: So how do you think this current focus on the opioid epidemic impacts the broader conversation when it comes to all substances in general?

BOTTICELLI: I think our perception of people with substance use disorders has a dramatic impact on public policy and on how we treat and deal people with addiction. So when you look at public opinion polling, there are a significant number of people who believe that people with substance use disorders are not deserving of treatment benefits, or that the biggest barrier to people's recovery is the fact that people aren't willing to quit. While I think we're seeing that conversation shift, there is still, I think, a significant amount of perceptual challenges that we face that dramatically lead in to public policy and our thinking about things like treatment benefits or providing people ample access to high quality care.

PERFAS: It's interesting to think about the stigma that goes around any substance, you know? And right now I think that the big focus is on opioids because it is seeing a rise in overdoses. But if you look at the data, alcohol is still responsible for the most death but it doesn't seem to hold the same stigma, I guess, that other substances have. So I wonder, do you think that.,I don't know, something's getting lost in the conversation when we try to fixate on sort of the drug of the day?

BOTTICELLI: I think because of the mortality linked to the opioid epidemic, and we obviously need to focus on that, I think we have lost sight of the fact that there are substances like alcohol that create and continue to create a significant amount of morbidity and mortality associated to this issue. We know that addiction, any addiction, is a disease of early onset and it often starts with the early use of alcohol. And you know part of my fear here even though it's really not being borne out in the data that you know, we're forgetting about the role that alcohol in and of itself plays in terms of people's addiction, but also the role that early alcohol use plays in setting for many people a trajectory toward addiction. I also think that you have to look at the opioid epidemic in the context of other significant issues that we're seeing play out across the United States. So for the second year in a row the United States has seen a decrease in life expectancy. No other Western country is seeing this. And if you look at some of the largest drivers in that, in the reduction in life expectancy they're drug overdoses, suicides, and diseases related to alcohol use disorders. So you know we have to continue to pay attention on a number of factors but also really begin to look at root cause issues.

PERFAS: I wonder if we talk enough about what is driving people to substances in general you know whether it's alcohol or opioids or marijuana or tobacco. Like what are those root causes and a lot of times, if you, if you really dig down, it just seems like people are hurting you know. They're looking to self medicate and substances, whatever the substance, become an outlet for that.

BOTTICELLI: You know I absolutely agree that you know you have to look at kind of the circumstances in people's lives as it relates to why people use it. I think there is not only a tremendous amount of physical pain that people have that, you know, really I think spurred, along with a number of other factors, this overprescribing of opioid pain medication. But there are many people who have profound psychological pain for whom alcohol and drugs become a way to blunt that sort of psychological pain. You know, we basically know that there are kind of two main drivers of addiction. One there is a very strong genetic predisposition to addiction, like most chronic diseases, but there are a host of of environmental and social factors. Things like racism and endemic poverty, early childhood trauma can really play a devastating role in a whole host of negative health consequences, including addiction. And you know the more and the longer that I do this work, the more that I see that unless we focus equal amounts of attention on people's social circumstances, those kinds of social determinants of health, that we're going to be continuing to see this ebb and flow of epidemics and not really get those root cause issues.

PERFAS: You know it almost seems like we'd be better off focusing on helping people overcome their pain, be it emotional or physical, instead of demonizing the specific drug that is a big issue in that moment.

BOTTICELLI: Even this current epidemic you know, I think we have to acknowledge that there have been many communities that have been hard hit, impacted by opioids for a very long time and I'm thinking specifically of communities of color and poor folks that you know, we know some of those circumstances really lead to significant drug use. And I do think that we have to look at some of these endemic causes. We have to look at things like isolation and how we kind of think about connection to other people and community and think about resiliency factors at both the individual and community level. We haven't really paid enough attention to those issues. And you know it's my hope that you know, this current epidemic and with the spotlight on it, we'll begin to think about how we really focus on some of those environmental and social factors.

PERFAS: One thing that Michael said is that there are so many powerful stories of people struggling with addiction who are now in recovery but what's difficult is that it's hard for them to talk about it. Society may be changing but there are still a lot of people who don't understand the complex challenges that go hand-in-hand with addiction and recovery.

BOTTICELLI: You know I think this is where we have a significant perception gap. When you look at polling data, a significant portion of people don't believe that treatment works, that don't believe that recovery is possible. And I think it's often because they don't hear or see nor do we as a society celebrate people's recovery. And you know, I work at a health care institution, where I see people getting better on a daily basis and see the profound change in people's lives when we give them good care filled with empathy and compassion. And you know I I think that people's personal stories can have a dramatic impact on chipping away at the perception that treatment is ineffective or there is not hope on the other side of addiction. Addiction is often characterized by a profound sense of isolation and hopelessness. And I do think that not only do we need to treat people with dignity and respect but really amplify the fact that people can and do get better.

AMANDA DECKER: I kind of say to people we have an addiction epidemic in our country, not an opiate epidemic. It's addiction in general. And that's been that way for years.

PERFAS: This is Amanda Decker. And she's a substance use prevention specialist in Avon, Massachusetts, a small mostly white working class suburb south of Boston. She works with youth and also hosts the Organizing for Change podcast.

PERFAS: What is the biggest substance issue facing youth today?

DECKER: Hands down alcohol and it's been that way for years. Just in our community when I first started we had 47 percent of youth in grades nine through 12 drinking on a regular basis and that's within the last 30 days. In the community that I'm in, we were very fortunate to get something called Drug Free Communities funding, which is funding specifically for youth substance use prevention and it's been eight years since I've been with them personally. And today that number is down to 13 percent of youth in grades nine through 12 in that community drinking on a regular basis. So I mean amazing significant progress has been made.

PERFAS: So if it's down to 13 percent, you know that kind of shows that even though alcohol is the biggest problem still the majority of youth are not actually consuming alcohol regularly. Correct?

DECKER: Absolutely. And that's really one of our main strategies. So what happens is that young people are susceptible to negative peer pressure. We all know that they're also susceptible to positive peer pressure. So when a young person goes into a room and their belief is everyone is drinking they are more likely to decide to drink themselves. Even though there's such a high number, 47 percent of kids that were drinking, we wanted to start talking about the 53 percent that were not drinking. And what we did is we created a bunch of media campaigns, focus groups, just ways to get the message out to let young people know there are many kids in your school that are making healthy decisions and really letting them know it's okay to say, I don't want to drink. Let's give them permission to say, I don't want to do that. Because when a young person feels that they're all alone, they are not going to make that healthy decision or they're less likely to make that healthy decision. They want to be part of the majority. And young people thought that 80 percent of their peers were drinking and that's just the culture. And we worked really hard to change that and measured that perception over the years. And as that perception decreased and kids began to believe that not everyone drinks the actual rates of use decreased as well.

PERFAS: Why do you think that misperception existed in the first place? Why did they think everyone was doing it even though clearly that wasn't the case?

DECKER: I like to tell a story of being in a cafeteria and you've got 100 kids in there and you've got that one young person who's really loud, outspoken. You know, everybody pays attention to them and they start talking about all the drinking that they did over the weekend and the parties they went to and they're just loud and talking about that message. And I think you know, there's 99 other kids in the room, but when we all walk out, we remember that one person who is being noticed and loud and kind of spreading that message. I don't think it's very popular in our culture to stand up and say, hey I was so sober last weekend. We've created a culture where we kind of glamorize just partying and all that kind of thing. And I also think, so when a young person hears that message being spread by a few, a handful of people, they begin to think that's everyone.

PERFAS: In this episode we're talking about the opioid epidemic and how that kind of fits into this conversation around substance use. I'm curious how does that impact the work you're doing? You Know if opioids are not really the biggest things that is impacting youth like is it complicating things like the constant conversation around that?

DECKER: Yeah I think that's such a great question. So we actually just had this conversation with some of my colleagues and we're saying how, what will happen in our community is people will look at the prevention strategies that we're using and they'll notice that we're talking about alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana, which are the three most used drugs among young people. And they'll ask us, how come you're not talking about heroin? And we'll go back to the data and we'll say the data shows that in our community, and I'm not saying every community, but in our community, our kids are not using opiates and they're not using heroin. They're using alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. And that's really hard for some people to believe because the opiate epidemic is getting so much notice.

DECKER: Amanda said that one way the focus on the opioid epidemic has complicated their work is the various approaches to prevention. Since mortality rates are so high with opioids, there's a lot of work being done via death prevention, which means helping people survive overdoses so they can get into treatment. But what Amanda and her team do is primary prevention. They try to look at the root causes and help young people avoid going down the road to substance use altogether. And data show that journey often starts well before an individual starts using opioids.

DECKER: The issues started so much, so much further back than where death prevention is. You know you look at that young person and who they were as a 15 year old their drugs that they started with, whether people like it or not, the facts are the facts, they started with alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, or the rare incidents prescription drugs. But their first drug that they used was typically alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana. Our our data shows that if you can prevent young person from using any substances until their brain is developed, their chances of ever having an addiction issue go down significantly.

PERFAS: It's interesting to hear, because it almost sounds like if you want to prevent heroin use later in life, it might actually be the most effective to target alcohol use as a youth.

DECKER: It is. Yep you're absolutely right.

PERFAS: Amanda said the number one thing is to find out what's driving youth to use substances in that specific community. They found that the youth in their community believed there were no trusted adults to talk to. So they changed that. They started using a practice known as Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment or SBIRT. This allows the school nurse to talk to every student during their regular screenings and catch it early if that student is using substances. They can then begin to identify the reason why. Every youth gets that conversation from a trusted adult. And it has had an amazing impact on those kids.

DECKER: It's been really powerful because a young person, that when you catch them that early, you really can help change the trajectory of addiction for that young person. Whereas if you had waited till they were out of high school, they already, they already have an addiction going on. But if you catch it early you can really intervene. And sometimes the intervention really is so brief you know the young person just needed some information or needed to feel like they were supported. One of my favorite stories, so now I've been doing this work for eight years, in this particular community, watching a young person come back to our school after having graduated and gone on to college. Come back and have a conversation with that young person and just say, you know, how are you doing in college? And they say back to me, you know I grew up in this community in Avon. There were so many positive things to do. People really cared about me making healthy decisions, that I never used any substances. I didn't drink until I turned 21. I am substance free today, like I do not have a struggle with addiction because my brain is developed and I never used those things because I grew up in this community. That to me was just so powerful, just talking with that young person and realizing... because in the world of prevention, a lot of times you don't know the name of the person that said, oh I'm not going to use drugs or alcohol. You just see the numbers, you see it go from 47 percent to 13 percent. Whereas when you work in the intervention field you know that young person because they're sitting right across from you. It was just, it meant so much to me to be like, this is why I'm doing this. Because young people like this girl can come back to me and say I grew up in Avon. That's the reason I didn't do these things. It just really touched my my heart.

PERFAS: Like Amanda said sometimes that intervention is just a brief conversation at a pivotal moment in a young person's life. There are a lot of things that drive people of any age to use substances and having that conversation early on can really make a difference. We still struggle to understand the nuances and complexity of addiction, whether it's to opioids or alcohol. But like Michael the executive director of Grayken said in his interview, it often comes down to people hurting, either physically or psychologically. So how can we identify the root causes so we can address the real problem behind addiction? I mentioned earlier that Michael himself is in recovery. Here's a bit of his story that he shared.

BOTTICELLI: You know, I always say that kind of my story is not unique and you know like many people in the United States, I came from a family with a long history of addiction. I started drinking at a very young age because that was the cultural norms that were part of not only my community but you know, certainly both in high school and college that seemed kind of part of the norm. Again we know addiction is the disease have early onset. And my story is you know pretty emblematic of that. But you know I don't remember anyone, a pediatrician a school counselor, anyone saying to me you know, well Michael, you know you come, you have a family history of this. So you know you can't drink like other people and without you know running significant risk of developing problems or seeing interventions at a very young age. And it wasn't until an intersection with the criminal justice system where I was basically forced to get help. I was in a car accident as a result of drunk driving, and basically the court mandated that I seek treatment. And you know, it wasn't until that point that I began to understand that I really needed, that I had a significant problem and that I really needed help. You know the other thing for me personally that I think get gets played out time and time again is the stigma that's still associated with addiction. And I recall distinctly understanding and knowing that I had a problem and know that I needed help, but was really afraid to get it. I was afraid of what my employer would think, of what my family and friends would think, that people would think that I was dumb or that I was weak-willed that I should be able just to buck up and conquer it on my own. And I think that we see that played out millions of times in people's lives, where people are too afraid to ask for help because they're afraid of what other people are going to think, that families are too afraid to ask for help for their loved ones because they feel some sense of shame and guilt. My own kind of personal story I guess gives me a kind of a deep understanding of not only missed opportunities and systemic changes but also how we need to continue to really chip away at the stigma that prevents so many people from asking for help.

PERFAS: No one is struggle free. I might go as far to say that very few of us are addiction free, if you define it broadly. Like Amanda said, we have an addiction epidemic. Maybe it's not a drug but it could be social media, food, gambling, video games, shopping... We can all relate to the experience of trying to cope with something that's just hard. Maybe that's a place of common ground to empathize with those struggling with substance use disorders and work to develop that important community of compassion and support.

In this week's newsletter, I've included some additional resources for you. If you haven't already subscribed, you can do so at csmonitor.com/perceptiongaps.

Finally thanks to everyone who made this episode happen. My producer Dave Scott, our studio engineers Morgan Anderson, Ian Blaquiere, Tori Silver, Jeff Turton and Tim Malone. Original sound design by Noel Flatt and Morgan Anderson. And a special thanks to all my volunteer editors: Mark Sappenfield, Ben Frederick, Noelle Swan,, Jasmine Heyward and Em Okrepkie.

And I'm Samantha Laine Perfas. Thanks for listening to Perception Gaps.

COPYRIGHT: This podcast was produced by The Christian Science Monitor. Copyright 2018.