The end of amateurism? What’s behind calls to pay NCAA athletes.

Loading...

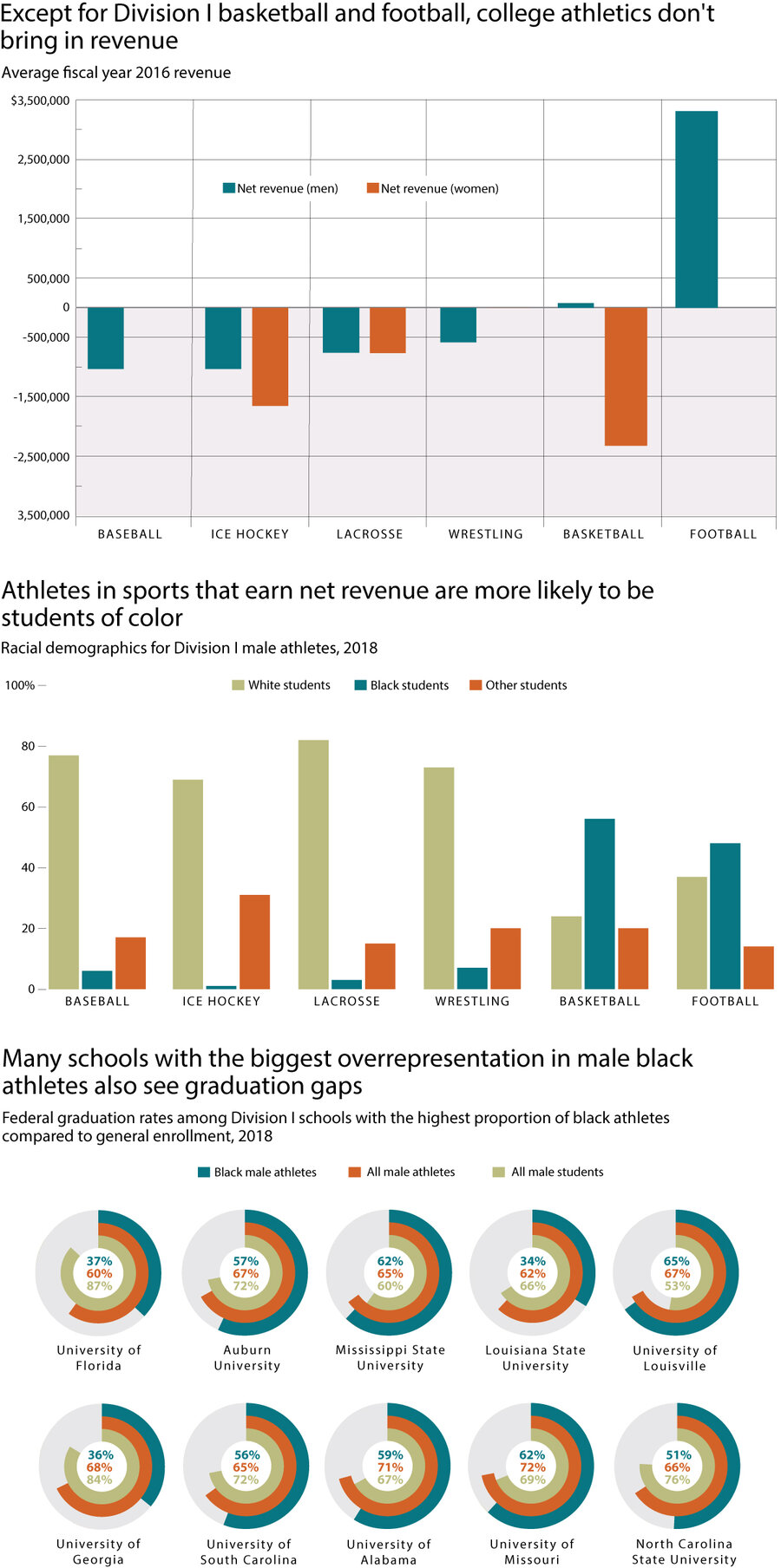

The Operation Varsity Blues admissions scandal spotlighted the influence of sports in higher education. But athletic revenue likely doesn’t contribute much to that influence, since, save for a handful of schools, college athletic programs don’t actually break even. The ones that on average do – Division I football and basketball – still don’t pay their players or let them earn money from their names, images, or likenesses. Those athletes are largely students of color, and their graduation rates (excluding transfer students) are generally lower. The system “is all predicated on the idea that a college scholarship is priceless,” says Victoria Jackson, sports historian and lecturer of history at Arizona State University in Tempe. “But [these athletes] are not earning the degrees.”

One reason is that athletic scholarships are annually renewable – a structure that looks awfully similar to an employment contract, says Dr. Jackson. On high-stakes football and basketball teams, players who perform poorly risk losing their funding, which makes finishing a degree much harder for most. And for the small proportion of athletes who do go professional, draft eligibility for the NFL and NBA allows them to leave school before graduating. Without assurances of a college degree or professional career, many critics view student payment as a necessary trade-off.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association, the body that regulates college sports, has argued that payment would sully its value of “amateurism,” which distinguishes it from professional leagues. But whether or not students receive it, universities are funneling money into athletic programs across the country. In 2017, the highest paid public employee in 39 of 50 states was a college basketball or football coach.

National Collegiate Athletic Association Revenues/Expenses Division I Report 2004-2016; National Collegiate Athletic Association, Demographics Database, 2018; Shaun R. Harper, P.h.D., Black Male Student-Athletes and Racial Inequities in NCAA Division I College Sports, University of Southern California Race and Equity Center, 2018

Why We Wrote This

Many student athletes serve a key role as ambassadors for universities. But how the players benefit educationally or financially isn't aways clear. A growing coalition is rethinking that relationship.

The push to pay players has roots in the 1950s and earlier, but new momentum may be building. A recent federal lawsuit removed caps on athlete compensation and benefits so long as they support educational needs, including textbooks and school supplies. And a bill allowing students to profit from their names, images, and likenesses is moving through Congress. State initiatives with similar aims in Washington and California have begun this year.

Ultimately, the athletes themselves might be the strongest reformers. “All it’s going to take,” says Dr. Jackson, “is one [player] boycott of March Madness or a college football playoff to stimulate pretty radical change.”