Stopping sexual assault: Students turn to video games to empower bystanders

Loading...

What do these three actions have in common?

- Starting a conversation about football.

- Offering a friend a feminine hygiene product.

- Responding to someone’s request for an “angel shot” at a bar.

They’re all ways that everyday people have intervened in situations that they worried could have led to a sexual assault.

Why We Wrote This

Sexual assault and dating violence can seem like intractable problems. But recognition is growing about how people can make a difference, without waiting for an emergency.

The first one happened when a student noticed a man plying her friend with vodka; she started a conversation about the NFL, prompting the man to get bored and leave. In the second, a student offered a creative excuse so a friend could escape sexual pressure at a party. The third, asking for an “angel shot,” is a tactic some phone apps and bartenders are promoting, to help patrons signal that they need assistance.

Sexual assault and dating violence seem so intractable that it can be tempting to wonder how they’ll ever be stamped out. It’s not always easy to spot the red flags, let alone know what to do about them. But there’s growing recognition that people don’t need to wait for an emergency to consider how they can make a difference.

“It’s really reframing it – that this is not a male problem or female problem, it’s a community problem,” says Sharyn Potter, executive director of the University of New Hampshire’s Prevention Innovations Research Center.

The need for people to become more empowered – and the potential for change when they do – is clear. In a survey of 27 campuses, 44 percent of students said they had witnessed a drunk person heading for a sexual encounter, but 77 percent of them did nothing, the Association of American Universities reported in 2017.

Among students who witnessed sexual harassment or violence, 55 percent did nothing. About a quarter of them said it was because they didn’t know what to do.

“Without competence, fear will run the show,” says Mike Domitrz, founder and executive director of the DATE SAFE Project. The key, he says, is to “give them skills that they realistically believe they can implement.”

More tech options

Young people are also at the forefront of developing bystander-intervention tools that resonate with their peers.

Two video game prototypes have shown promise, for instance, after Professor Potter’s UNH team collaborated with students and with Dartmouth College’s Tiltfactor Laboratory.

One is a team trivia game that mixes campus information and pop culture with items related to preventing sexual assault. The other is a space adventure game that presents scenarios and options for how to respond.

“By inserting yourself in these situations and playing through them, you’re getting a much clearer understanding of what you can do in real life,” says Hannah Hodges, who helped create the games during her senior year at UNH.

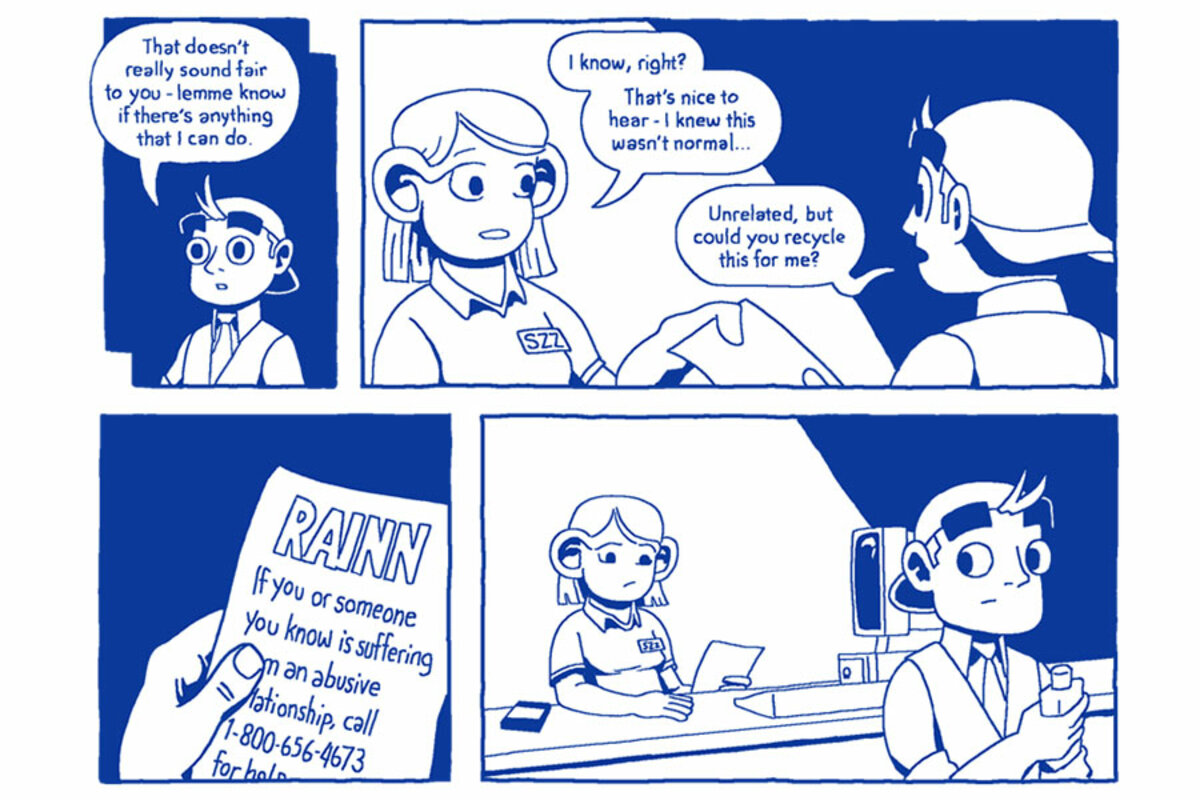

In one scenario, the player has the option to offer someone in an abusive relationship information about a hotline. Another has the player overhearing sexist insults and choosing ways to step in.

Sexual violence is on a continuum, and when people make “sexist comments and they’re not called out,... it’s easier for the more severe violence to occur,” Potter says.

In a study of 300 college men and women who played the games, the men’s knowledge about bystander intervention went up, as did their willingness and confidence to intervene. Those elevated levels were statistically significant and lasted at least four weeks.

Video games on their own won’t shift a campus culture, but they are one way to widen the audience for more-comprehensive prevention strategies.

A growing number of students are also using phone apps that address sexual assault. The uSafeUS app developed by Potter’s team includes features for everyday use – one, called “time to leave,” can be set for an excuse to leave an uncomfortable date, for instance. Students in focus groups said that without such features, they wouldn’t keep the apps with sexual assault resources, because most don’t believe it will ever happen to them.

Phone apps help open up conversations and “make the problem more salient in students’ minds,” says Amanda Fusting, a student at the University of Maryland, in College Park, who’s helping to spread the word about the UASK DMV app at campuses in Maryland, Virginia, and Washington, D.C..

During the hearings leading up to the appointment of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, one of Ms. Fusting’s family members asserted that sexual assault is always a repetitive behavior, so if he had lived such an upstanding life, he was unlikely to have committed an assault in high school. Fusting offered a different perspective, informed by her participation in several campus groups. There are many serial offenders, but “it is not necessarily true that it will be repeated,” she says.

To some degree, the politically polarized hearings “locked people into their personal beliefs,” Mr. Domitrz says. But by using gender-neutral examples, he tries to avoid stereotypical assumptions about survivors and perpetrators, and that helps engage people who hold a spectrum of views.

Starting early

Before college isn’t too soon to start, prevention researchers say. The boys on a high school basketball team in Los Angeles came up with a way to challenge each other when they were halfway into A Call to Men’s LIVERESPECT curriculum, says trainer Jay Taylor. Any time they heard someone put a teammate down with a comment derogatory to women, they would call out “Man Box.” It was a friendly reminder to shed some of the negative ways society pressures men to show dominance.

Ms. Hodges, who has since graduated from UNH, once walked up to a drunk stranger in a bar and directly confronted him after he grabbed a woman’s arm. Just as society shifted to stop behaviors like drunken driving, she and others say they hope the culture is now shifting toward a greater willingness to put up roadblocks to sexual assault.

Hodges felt comfortable being direct, but “you don’t have to put on your superhero cape,” Potter says. “Turning down music or turning on lights at a party can go a long way.”

Confidential help is available by calling 800-656-4673, the National Sexual Assault Hotline, operated by RAINN.