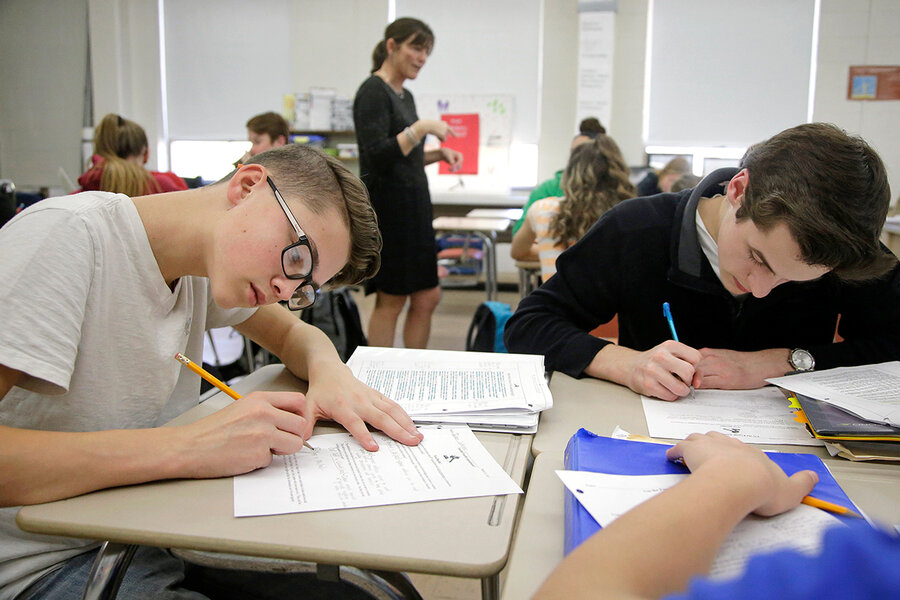

Racial gaps in education: How much do voters care?

Loading...

Americans like to think of their public schools as promoters of social mobility and equality. But the way race, class, and power play out in local voting booths may be standing in the way.

Reelection of school board members tends to be tied to the achievement scores of white students – even in districts that are majority Hispanic, a new study shows. The scores of black and Hispanic students – and their gaps relative to whites, often have little to no bearing on such elections.

In addition, many school board members do not see closing racial gaps as important to their voters, report Patrick Flavin of Baylor University in Waco, Texas, and Michael Hartney of Lake Forest College in Lake Forest, Ill., in the July 2017 issue of American Journal of Political Science.

“One of the fundamentals of democracy is we kick members out of office if they are not performing well,” Mr. Flavin says, but this study suggests that applies only to those who are not doing well on behalf of whites.

The bipartisan No Child Left Behind law was meant in part to reveal groups of students who weren’t reaching important benchmarks in reading and math. In turn, the public could pressure schools to bring up the scores of underperforming groups.

Public not informed on racial gaps

The causes of these gaps are varied, deep-rooted, and complex. But “part of the problematic politics of educational equity is that people are remarkably uninformed about racial achievement gaps in the US … and about inequality broadly speaking,” says Patrick McGuinn, a political science and education professor at Drew University in Madison, N.J.

Most of his students, who largely hail from middle- and upper-income suburbs, are shocked when he shows them data on segregation and disparities in school funding.

The new study analyzes school board elections in more than 900 California districts between 2004 and 2013. The state was a good place to start because of its diversity and a robust set of school data that officials have made available to parents and the public.

School board incumbents were more likely to be reelected when white students’ scores increased, and more likely to lose when those scores went down. Hispanic achievement had little bearing on the results, and black achievement even less.

This held true even in districts where black and Hispanic students made up large or majority shares of the student body, the study found.

Test scores don’t offer a full picture of student achievement, but they are the most widely available and publicized data points people use to judge school performance.

Little pressure to close the gaps

Another component of the study surveyed 290 school board members, and about 40 percent indicated they felt little pressure from their constituents to close racial gaps.

“Because racial minority students tend to receive the least attention from voters at election time…, this paper calls into question the premise that popularly controlled public schools are capable of promoting greater equality in political participation,” the authors say in the study.

Many Americans don’t think achievement gaps relate directly to school quality or to injustice in society.

The Flavin-Hartney study looked at citizen survey data showing half didn’t know about the racial gaps, and of those who did, only 24 percent believed they were due to school quality. (The 2001 data set was the best available, Flavin says, though he acknowledges its age makes it less-than-ideal.)

Another study, in 2016, found that 64 percent of American adults said it was a high priority to close test score gaps between poor and wealthy students, but only about a third placed priority on racial gaps.

The public also showed a preference for addressing income-based gaps when it came to potential solutions, such as teacher bonuses to serve the disadvantaged group, according to the 2016 study, by Jon Valant of Tulane University in New Orleans and Daniel Newark of the University of Southern Denmark in Odense.

When asked what they saw as possible causes of racial achievement gaps, the public tended to rank them in this order: parenting, student motivation, discrimination and injustice, and genetic differences.

About 44 percent said that none of the racial gaps could be attributed to discrimination or injustice. Only 10 percent said these factors accounted for a great deal of the gaps.

Perhaps not surprisingly, those who saw injustice as a cause of the gaps cared more about trying to close them.

Low turnout for elections

None of these findings surprise Mr. McGuinn of Drew University, partly because of “the underlying political realities” of school board elections.

Nationally, these elections have low turnout, on average 10 percent or less, he says. And those who show up – such as people mobilized by teachers unions – are often organized around particular issues.

The California elections in the study are not typical of the nation. They were all held in November, when more voters tend to show up because of other state and federal elections taking place at the same time. But in the vast majority of places, school board elections are held at separate times.

That has its roots in the historical Progressive era, when there was an attempt to depoliticize education and leave it more in the hands of professional educators, McGuinn says.

Now, he says, “you are seeing, for better or worse, politics kind of reasserting itself inside the schools, in large part because the schools are underperforming … and failing to address achievement gaps.”

Around the country, for instance, a number of school districts have come under mayoral control or state takeover. And some places, such as New Jersey, have been working to shift school elections back into November.

Flavin says his research could be interpreted in a variety of ways. Instead of turning away from locally elected school board control of schools, for instance, “one fix might be to further publicize these disparities.” It’s important for the public to understand, he says, that even if schools don’t cause the gaps and can’t fix them quickly, they are “the most likely target for disappointment [and accountability for] how different groups are doing.”

But historical precedent suggests that it’s not an easy task to get local voters to open their eyes to the challenges in their own schools. Many surveys show people tend give bad grades to public schools in general, but good grades to their own schools.

“People don’t want to hear bad news about their schools,” McGuinn says. In his own community, for instance, where the schools do well overall, people reacted angrily when the state labeled them as needing improvement because of the racial achievement gaps.