How Boston achieved its record high school graduation rate

Loading...

| Boston

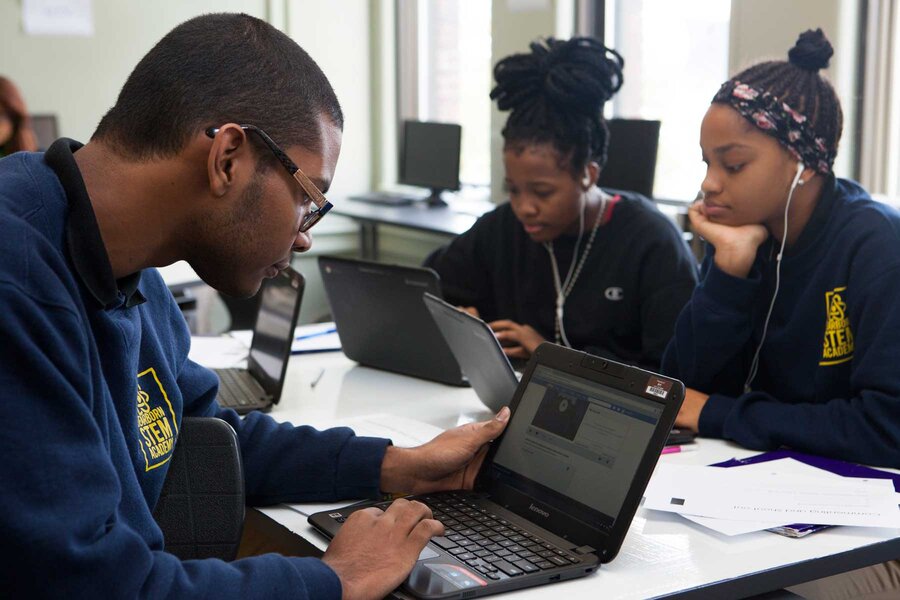

Dante Omorogbe might sound like any other school kid rattling off his grades: “A - for senior math, A- in Algebra …,” but for the 21-year-old senior, they mean so much more.

Mr. Omorogbe originally was set to graduate in 2014. That was until, after a fight with his dad, he was “tossed” out on the street. Eventually, his grandmother took him in for a while, but with her working during the day, Omorogbe needed to care for his gravely ill grandfather. School eventually became too much, so he dropped it.

For many students across the country, circumstances like Omorogbe’s can derail them from the high-school-to-college track in ways that alter their trajectory for life. In his case, Boston Public School’s Re-engagement Center was able to connect him with EDCO Youth Alternative, a school that provides extra support such as counseling to nontraditional and struggling students. He started in September 2016 and will have his diploma in hand by May.

“I have my counselor who calls me every day. I miss school for two, three days, she’ll call me, say, ‘are you OK?’,” says Omorogbe. “All the vacations, she’ll call me; for my birthday, she’ll bake me a cake.”

Ten years ago, Boston high school students like Omorogbe were far less likely to get their diploma. In 2006, the city’s graduation rate was languishing at 59 percent. Last year, the number of Boston students who graduated in four years hit a record high of 72.4 percent. Statewide, the graduation rate inched up to a record 87.5 percent from 87.3 percent last year, according to state figures released Tuesday. The numbers of young people graduating has shot up thanks to a host of “equity” focused reforms, such as re-engagement programs, the turnaround of chronically struggling districts, and strong regulation of traditional public and charter schools, wrought under a landmark Massachusetts Education Act.

“You're seeing the accumulated progress and gradual incremental progress … with particular attention toward equity and closing the achievement gaps,” says Paul Reville, a professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education and former secretary of Education for Massachusetts. “And dealing with one of the most significant problems that we have in education these days, which is people dropping out without a high school education and having no place to go in our economy.”

Big gains by students of color

Education experts say Boston's new record was particularly encouraging because of the double-digit gains by the city’s African-American and Latino students in the last decade – 13.6 and 16.5 percentage points respectively. In 2006, African American students graduated at 55.7 percent, compared with 69.3 percent in 2016. Latino and Hispanic students jumped from 50.6 percent to 67.1 percent over the same period.

And strong turnarounds in urban centers beyond Boston have played a substantial role in the state's overall increase. For example, in one of the Bay State's former mill towns, Lawrence, the first district in the state to be placed in receivership in 2011, saw its four-year graduation rate jump from 52.3 percent that year, to 71.4 percent in 2016. Re-engagement programs were one integral part of receiver Jeff Riley's turnaround plan for the city, which has a more than 90 percent Latino student population.

But with roughly 5,500 kids across the state still dropping out of high school every year, Professor Reville and others acknowledge that Massachusetts, widely recognized as having the nation's leading education system, still has a long way to go.

Next steps

Probing the numbers a little deeper, Reville emphasizes two potential next steps for keeping the graduation rate trending higher and increasing its reliability as a measure of students’ actual readiness for college and career.

First, Reville says it is problematic that the five-year graduation rate – indicative of those students who take an extra year to repeat failed classes – is only marginally higher than the four-year graduation rate. He says that is because educators are essentially just giving students who struggled with the material the first time the same work again without significantly changing the way they teach it.

Second, despite the relative successes of the state’s standardized testing system, he calls for better and more frequent signals to be sent to parents and students about how they are tracking “relative to what they'll need to be successful” in college or their career. Currently, the state clears students to graduate as long as they pass the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment (MCAS) in 10th grade. But Reville says this is not enough, given students are expected to learn a lot more in those final two years. Many are holding diplomas that often have not actually equipped them for their next steps after graduation.

“Maybe there's some signaling that needs to happen in the 11th grade, for example, and maybe we can use technology in turning around assessments more quickly to give students and their families an indication of whether, for example, they're on track to do college math work, which many of our graduates are not,” Reville says.

Still, for students like Omorogbe, getting to graduation has meant a total change in aspirations since his days as a dropout, bouncing from house to house and working at a party supply store. Now he plans to go into social work to help other kids walking a similar road.

“I’ve been in positions where [social workers have] never been in my shoes, so they can’t really help me,” he says. “So if I become a social worker I can help the kids who may come in at a young age who might have issues where I can say, 'You know, when I was that age I did this ... and this is how you get through it.’ ”