Nobel Prize for physics: How LEDs change the world

Loading...

Three scientists took home the Nobel Prize for physics Tuesday for “the invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes which has enabled bright and energy-saving white light sources,” according to the Nobel committee. Previously, the lights were limited to red and green diodes, but were missing a crucial component to create everyday white light. Many hail the addition of the blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as a revolutionary breakthrough in lighting technology that has already transformed everyday devices and is illuminating parts of the world that have remained in the dark.

So why all the fuss about something as seemingly simple as better, more efficient light? As the Nobel committee puts it, "Incandescent light bulbs lit the 20th century; the 21st century will be lit by LED lamps."

Nearly a fourth of global electricity consumption is used to brighten dark spaces. Traditional incandescent and fluorescent lights are notoriously inefficient with much of the energy used to produce light lost in the form of heat (it's why you wait a few minutes to change a light bulb after it burns out). Meanwhile, LED lamps last longer and use a fraction of the energy to produce the same, if not more, light.

That has huge consequences for the developed world, and cities, offices, and homes are already swapping out old bulbs for the brighter, more efficient LEDs. But the technology has perhaps even greater significance for the more than 1.5 billion who lack access to electricity grid. In Sub-Saharan Africa, that's two out of three people. By requiring less power, LEDs perform better than traditional lights on portable, scale solar energy, which makes spreading electricity to rural, off-grid regions much easier.

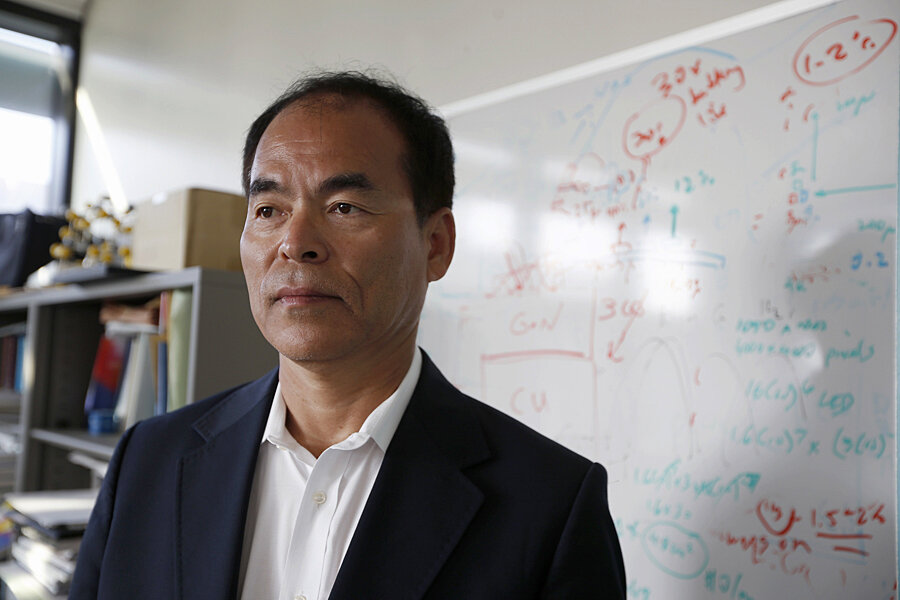

"It is very satisfying to see that my dream of LED lighting has become a reality," Shuji Nakamura, one of the winning scientists, said in a statement released by the University of California, Santa Barbara, where he is a professor. "I hope that energy-efficient LED light bulbs will help reduce energy use and lower the cost of lighting worldwide."

The other two winners were Japanese scientists Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano.

A light's efficiency is essentially the amount of light produced (measured in units called lumens) by a specific amount of electric power (measured in watts). For comparison, a traditional incandescent light bulb can produce about 16 lumens per watt. Fluorescent lights are a bit more efficient, producing 70 lumens per watt. LEDs, at their peak, have produced up to 300 lumens per watt.

It's no wonder, then, that the nascent technology is booming. General Electric forecasts that LEDs will account for about 70 percent of a $100 billion market by 2020, compared with 18 percent in 2012, reports Reuters. Right now, about 13.2 million LEDs are used for roadway and highway lighting worldwide, according to Navigant Research, a Colorado-based market research firm. The group expects that number to jump to 116 million in 2023. Companies like Boston-based Digital Lumens is combining the technology with advanced sensors and web communications to develop lighting systems that slash energy use (and costs) by up to 90 percent for warehouses and other sprawling indoor spaces.

The catch is that many LED lamps still have an upfront sticker cost higher than the average incandescent or fluorescent light bulb. But that price is dropping dramatically, and because LEDs last longer (10 times longer than fluorescents and 100 times longer than incandescents), the price over the product's lifetime tends to be lower. Another catch might be what analysts call the rebound effect – that by making lights more efficient we just end up using more of them thereby canceling out some or all of the energy saved. Still, most believe that represents just a fraction of total energy saved and should not discourage advances in efficiency. For those reasons and others, many say LEDs will continue to spread rapidly across the globe.

"It is not just for lighting Christmas lights on the streets of Stockholm in December," Nobel committee member Olga Botner told the Associated Press, "but really something that benefits mankind, particularly the Third World."