Did 2008 Wenchuan quake strike because China filled a reservoir?

Loading...

Scientists have seen this one before: Fill a reservoir behind a new dam, and, oops, you trigger an earthquake nearby not long after the lake is topped off.

Now, a team of researchers led by the University of Colorado's Shemin Ge suggest that this could well be what happened with the devastating Wenchuan earthquake in China's Sichuan Province in May 2008.

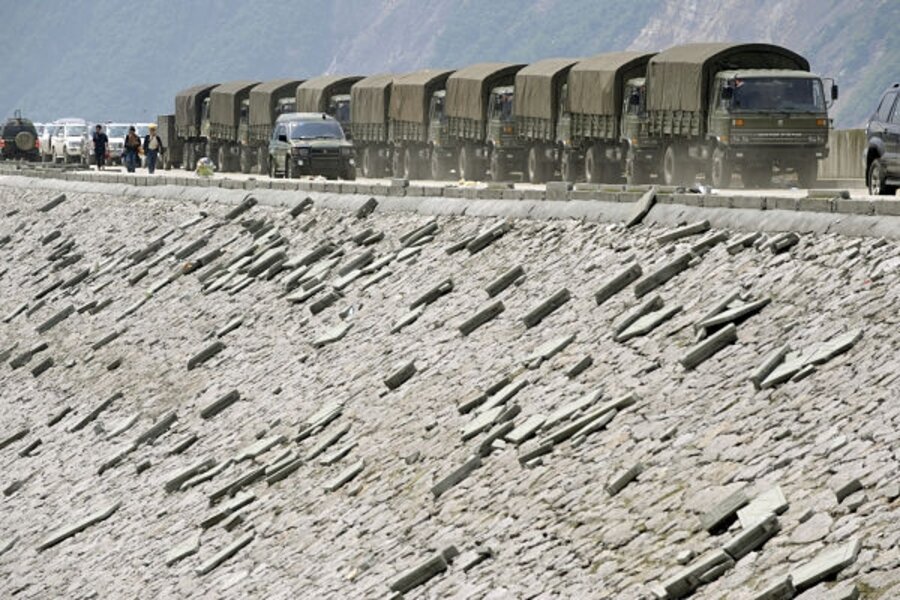

According to the Chinese government, the magnitude 8.0 quake left nearly 68,000 people killed, some 374,000 injured, and 18,500 people listed at the time as missing. Some estimates put the disaster's price tag at more than $75 billion. You can read more about the quake here, here, and here.

The reservoir in question is the Zipingpu Reservoir. It was filled in late 2005 and reached its maximum water level in December 2006. The reservoir is situated between the two faults that ruptured during that quake.

One of the two faults, the Yingxui-Beichuan Fault, virtually borders the reservoir; the second is roughly four miles away. The quake's epicenter was roughly 12 miles from the reservoir.

How would a reservoir affect nearby faults? The most obvious possibility is the weight of the water. It could add stress to a fault. Indeed, that was the focus of initial attempts to estimate the reservoir's possible influence on the faults responsible for the quake.

Last December, for instance, Columbia University's Christian Klose presented an analysis of the event at the American Geophysical Union's annual meeting in San Francisco implicating the extra weight of the reservoir's water.

To be sure, the region already is strained by the slo-mo collision underway between the Indian subcontinent and the rest of Asia's underbelly. But Dr. Klose noted that several observations put the reservoir under suspicion: how the crust responded when 320 million tons of water filled in behind the dam; how slip along the Yingxiu-Beichuan Fault was distributed during the quake; and the geographical distribution of aftershocks.

In short, the fill-up added roughly 25 years worth of stress to the fault, by one estimate. And when it ruptured, the fault responded just the way one might expect if the added mass of the water was present.

Dr. Ge's team adds another wrinkle to the discussion: the reservoir water's potential role as a lubricant for the fault. They used what's known about the characteristics about the crust beneath the reservoir, as well as microquakes local residents reported feeling as the dam was being filled, to estimate the pace at which water from the dam could in effect seep down through the crust to affect the faults.

When looking at the combined effect of added weight and water seepage, the changes in stress along the faults involved were comparable to those that would be induced if a large earthquake had happened nearby.

The stress patterns would have in reduced the likelihood of slip on the more distant of the reservoir's faulty neighbors. But it would have encouraged slip along the Yingxiu-Beichuan Fault. The results appear in the Oct. 28 issue of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Ge's team acknowledges that more information is needed to better test how closely the the changes in microquakes reflect changes in stress on the fault.

The team notes that microquake data prior to 2004 either weren't gathered or aren't available to the public. So there's no way to do a before-and-after check.

Still, she and her group say that their research shows how water diffusing through the crust could change the stress in ways that hastened the timing of the devastating quake by anywhere from tens to hundreds of years.

Editor’s note: For more articles about the environment, see the Monitor’s main environment page, which offers information on many environment topics. Also, check out our Bright Green blog archive and our RSS feed.