When the floods surged, a focus on readiness helped Vermont

Loading...

| Londonderry and Brandon, Vt.

At 10 p.m. Monday, Susan Brown watched the rushing water of the West River as it carved through the mountain town of Londonderry, Vermont, just yards from Jelley’s Deli Convenience Store, her mother’s market. Despite storm warnings, the river looked low so she headed home for bed. But by 2:30 a.m., the police scanner was going off. Water was rising. Roads were closing.

“I called my mom and said I’m heading up to the store to start packing things up,” says Ms. Brown. Even though by 3 a.m. she was lifting items off the floor to countertops, it wasn’t enough. The next morning, Jelley’s Deli was under 3 feet of water. This had happened before. During Tropical Storm Irene in 2011, the store sustained $250,000 in damages. But this time, the water was 6 to 8 inches higher.

As the water receded Tuesday, the town residents started showing up at the mud-caked, water-scoured store – dozens of them – hauling out damaged goods, emptying freezers, and offering hugs, home-baked cookies, and bottled water. Jelley’s is an institution in Londonderry. The deli and liquor market serves hundreds of lunches a day for town residents and visitors, and its owner, Bev Jelley, who has operated the store for the past 30 years, is beloved.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onBack in 2011, Tropical Storm Irene gave flooded Vermont a wake-up call. Efforts since then to build resiliency – alongside a humanitarian spirit – are helping this week.

“We’ve been through the floods before. It’s just a lot of work, and this was a freak storm,” says Ms. Brown, debris strewn about her boots and spilling across the parking lot. “I’m sorry for my mom to go through this again, but she wants to rebuild. That’s just who she is.”

Given the unpredictability of natural disasters, alongside good planning, there’s no substitute for neighbor helping neighbor – in small-scale ways like at this market or in larger ways, supported by donations and government aid. But this week has also shown the power of readiness. Most people stayed safe, and damage would have almost surely been worse without significant post-Irene initiatives, which included removing buildings and homes from flood plains, rebuilding bridges to withstand rising river levels, and expanding drainage systems like culverts. As cleanup begins and the current levels of damages are assessed, such adaptation will likely continue.

“Irene was a very traumatic event for many, many people,” says Sue Minter, who served as the state’s Irene recovery officer in 2011. “But I think we’re also so much more prepared and ready than we ever were before. Everybody was a little bit stunned the last time. And this time people are already organizing mutual aid groups, volunteer groups, business support systems. Because we’ve been through this before, we know we need each other and we know how to work together to do unimaginable and impossible tasks. And I think that’s just the other side of that story, of being prepared, and being resilient and being there for one another.”

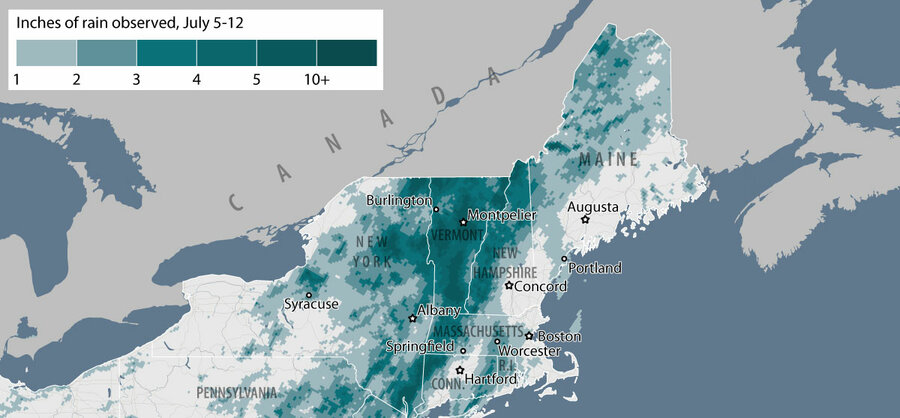

How floods surprised many

Unlike when Tropical Storm Irene hit in 2011, this time most residents didn’t think much about the slow-moving storm that marched across upstate New York on Monday, until it started dumping 6 to 9 inches across mountaintops and rivers already saturated from a wet June. Flash flood warnings swept across the state, catching residents off guard and quickly submerging the downtowns of Montpelier and Waterbury as officials anxiously watched rising levels at the Wrightsville Dam. The dam held, but flooding damages have been significant. Gov. Phil Scott submitted a request for a major disaster declaration to President Joe Biden. Crews got to work shoring up roads, removing trees, and beginning the cleanup. And across the state, fundraisers and donations have begun to pour in to help renters, homeowners, and small-business owners recover.

“We see flood-related erosion every time we get a flood, which is pretty much annually somewhere around the state, just not statewide. But it was particularly high with this event because the rain was a longer duration event over multiple days,” says Rob Evans, program manager for Vermont’s Watershed Management Division in a phone interview.

In 2011, the tropical storm resulted in three fatalities and more than $730 million in damages statewide. But in the decade since, communities across Vermont have slowly but steadily made changes to how they manage increased water flows. Instead of workers dredging rivers, which can result in faster rivers, courses were rebuilt to meander. Homes were removed from flood plains, and new building codes required electrical units to be on the first floor or higher, says Ms. Minter, who is now executive director of Capstone Community Action in Barre, Vermont. Through the Vermont Resiliency Project, a collaborative initiative on local and state levels, communities developed and implemented plans for better flood resilience.

“We did a lot to be proactive. I think it’s made a difference,” says Ms. Minter.

Resiliency, neighborliness, and community organizing are as much a part of the ethos of Vermont as its maple syrup, ski slopes, and general stores. Each small town has its own particular interpretation of those characteristics, whether it’s showing up to help a flooded store owner in need or adapting to a changing climate.

A culvert makes a difference

An hour’s drive from Londonderry is Brandon, Vermont, a town seeing results of its resilience planning at work. The road between Londonderry and Brandon tells the tale of this week’s events. Pastoral scenes and wildflowers rim the roads, as do flood-carved menacing gullies in their sandy shoulders. A bridge is washed out on Cobble Ridge Road. Heavy machinery operators in Ludlow, Vermont, work to remove enormous piles of mud and rocks that slid down Okemo Mountain and wiped out its town center.

But in picturesque Brandon, where American flags snap along Main Street, things look and feel much different. The town was built along waterfalls of the swift-flowing Neshobe River in 1761. Water is central to the town’s identity. It’s been certified as having the cleanest drinking water in the state, and was once a source of mechanical power. But it also means the town has sustained periodic flooding, sometimes catastrophic. In 2011, Irene flooded the downtown, washing out roads and lifting the Brandon House of Pizza off its piers into the center of the road.

Town leaders knew something needed to be done. With assistance and guidance from the Vermont Economic Resiliency Initiative, Brandon residents taxed themselves more than $600,000 toward a $2.5 million overflow culvert project so the river would not rise up and rush over the street. It also used money from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to remove houses from the flood plain.

Those efforts have proved to be a wise investment. This week’s storm had no impact. Town Manager Seth Hopkins is quick to point out a variety of reasons, including lower rainfall than other parts of the state, as contributing factors, but it also means the new 6-foot-tall, 12-foot-wide, and 238-foot-long culvert is doing its job.

“Our river here is an alluvial river. It comes down a mountainside and then it wants to fan,” says Mr. Hopkins, sitting at a table at the Town Office building, strewn with images that show damage from Irene along with the town’s resiliency blueprint plans. The culvert helps the river stay to its natural course. “We can live in harmony with what Mother Nature is going to do, and we need to give it some space to do its thing.”

Brandon was able to build its culvert with assistance – three-quarters of its project was paid for by a state of Vermont Hazard Mitigation Grant.

Experts say the road ahead may include more of the same – with federal funding practices having evolved, since Irene, with an eye toward sustainability and climate resilience.

“If we need a 72-inch culvert, and our rule requires the sizing to get 72 inches, FEMA will reimburse towns now to put in that 72-inch culvert,” says Mr. Evans, with the state’s Watershed Management Division. “That’s a big deal because, in light of a changing climate, we’re actually not putting in undersized infrastructure. We’re putting in the right-sized infrastructure that will hold up better over time,” he says.

Statewide, the way water flows and the responses to it are as individual as the many towns. Sometimes that means simply dealing with periodic floods.

“One of the challenges for Vermont is these narrow valleys with no place for towns and roads to move. You can make a culvert bigger, and you can build infrastructure to withstand [stronger] storms, but other than that, there’s not much you can do,” says Chris Klyza, professor of public policy, political science, and environmental studies at Middlebury College.

Neighbors giving aid

For now, this state’s deep spirit of community is operating in overdrive.

The town of Waterbury along the Winooski River has been washed out and rebuilt time and again. At Waterbury Sports, most of the inventory was, fortunately, either stored above the waterline or salvageable. But days of work lie ahead – including scrubbing down the basement to prevent mold – and volunteers have been showing up to help with all of it.

“This community is awesome,” says co-owner Caleb Magoon. “We’re getting the help we need.”

A few blocks away, at Stowe Street Cafe, owner Nicole Grenier has collected $12,000 in donations over the past few days to fund hot meals and coffee for neighbors affected by the flooding. People walk up to the counter and order what they want, for free.

“We just feel really compelled to advocate for doing better as a society, and making different choices, so that we can perhaps prevent some of these horrific outcomes that we’re all having to respond to,” says Ms. Grenier, who also distributed food after Tropical Storm Irene with her then-3-year-old son.

Back in Londonderry, Ms. Jelley of Jelley’s Deli arrived for another day of clearing out and throwing away, and offering cold bottles of water to two tired journalists.

“I thought, ‘I can’t do this again,’” she says, her gray pants tucked into boots decorated with stars, clouds, and rainbows. But then she got a good night’s sleep, pulled out a fresh yellow pad and pens, and started making lists, just as she did after Irene, making calls to her insurance agent and FEMA, which is already sending a representative to tour the damage.

Ms. Jelley plans to rebuild.

“Knowing how much this store means to so many people, ... I knew in my heart that I would need to do it,” she says. “It’s a commitment of love.”

Staff photographer Riley Robinson and staff writer Troy Sambajon contributed reporting for this story.