Charting a global drought – and the world’s quest to respond

Loading...

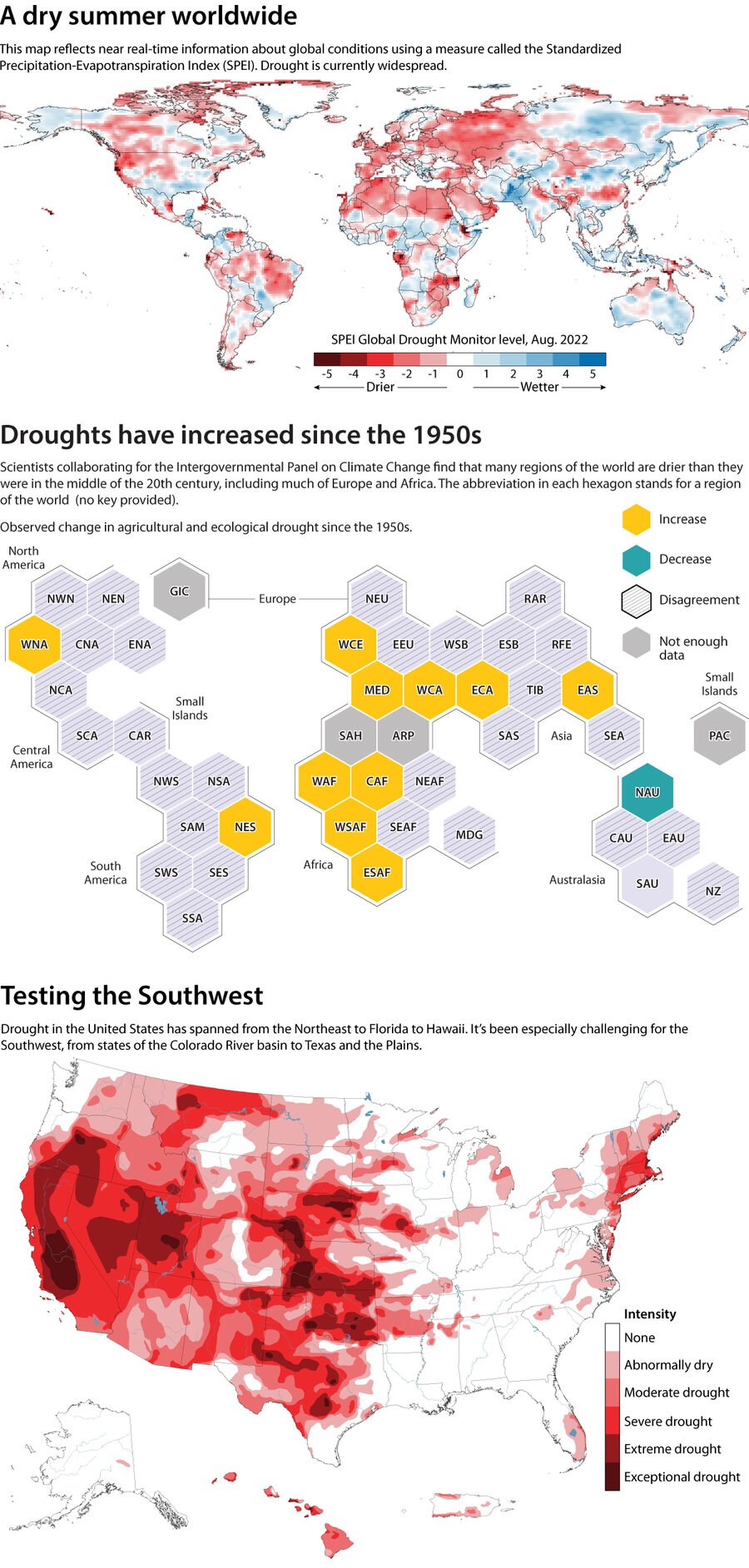

As we pass the official end of summer in the Northern Hemisphere, drought persists in many areas, from drying lake beds in the southwestern United States to European rivers where once-sunken warships are now exposed to public view. In the Southern Hemisphere, a lack of rain is creating an increasingly dire situation in the Horn of Africa. Chile faces its 13th straight year of drought.

All this has stirred growing concerns about how climate change may be affecting regions’ ability to maintain traditional farming output and sustain water supplies. But these concerns are also putting fresh focus on action in response.

“Droughts, along with other kinds of climate change impacts, are indeed already becoming more intense, more frequent, lasting longer,” not necessarily in all places but in general, says Rebecca Carter of the World Resources Institute in Washington, citing the published consensus of global climate scientists.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onDrought has created stress on water supplies and agriculture in numerous parts of the world. This adds urgency to getting better at responding. Early warning systems are just the start.

Both recent experience and the scientific assessments “should convey a sense of urgency, compelling everyone to build resilience against future drought risks,” Ibrahim Thiaw, executive secretary of the U.N. Convention to Combat Desertification, wrote this summer.

At United Nations meetings this week in New York, one priority for U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres is to build support for expanded early warning systems intended to cover every person on Earth from conditions such as drought, heat waves, and floods.

Dr. Carter, who leads the World Resources Institute’s climate resilience practice, calls this “a really important first step,” which then will need follow-up.

For farmers, next initiatives might be drought-tolerant seeds, more insurance against crop failures, and even changing where they farm in the first place, she says. People “need time to figure out what it’s going to mean for them, rather than waiting until the crisis hits and then expecting people to be able to change that quickly.”

From farms to cities worldwide, new steps to manage water are needed in many areas. Dr. Carter, with roots in Tucson, Arizona, points to the Colorado River basin as a prime example, where states are now having to rethink old assumptions about water use. A knock-on problem: Hydropower is also depleted when reservoirs sag.

Some actions might help both to adapt to climate change and to slow it. Lands that lose forests and vegetation are more susceptible to runoff, degrading soils and worsening floods and droughts when they occur. Reforestation is a nature-based solution that can build resilience and also mitigate climate change, Dr. Carter says, “because those trees store carbon.”

In a U.N. report earlier this year, Mr. Thiaw said, “One of the best, most comprehensive solutions is land restoration, which addresses many of the underlying factors of degraded water cycles and the loss of soil fertility.”

He also pointed to the opportunity for nations to shift from “reactive” or “crisis-based” actions toward longer-term planning, policies, and partnerships.