Saving starving manatees: Can Florida solve a man-made crisis?

Loading...

| Orange City, Fla.

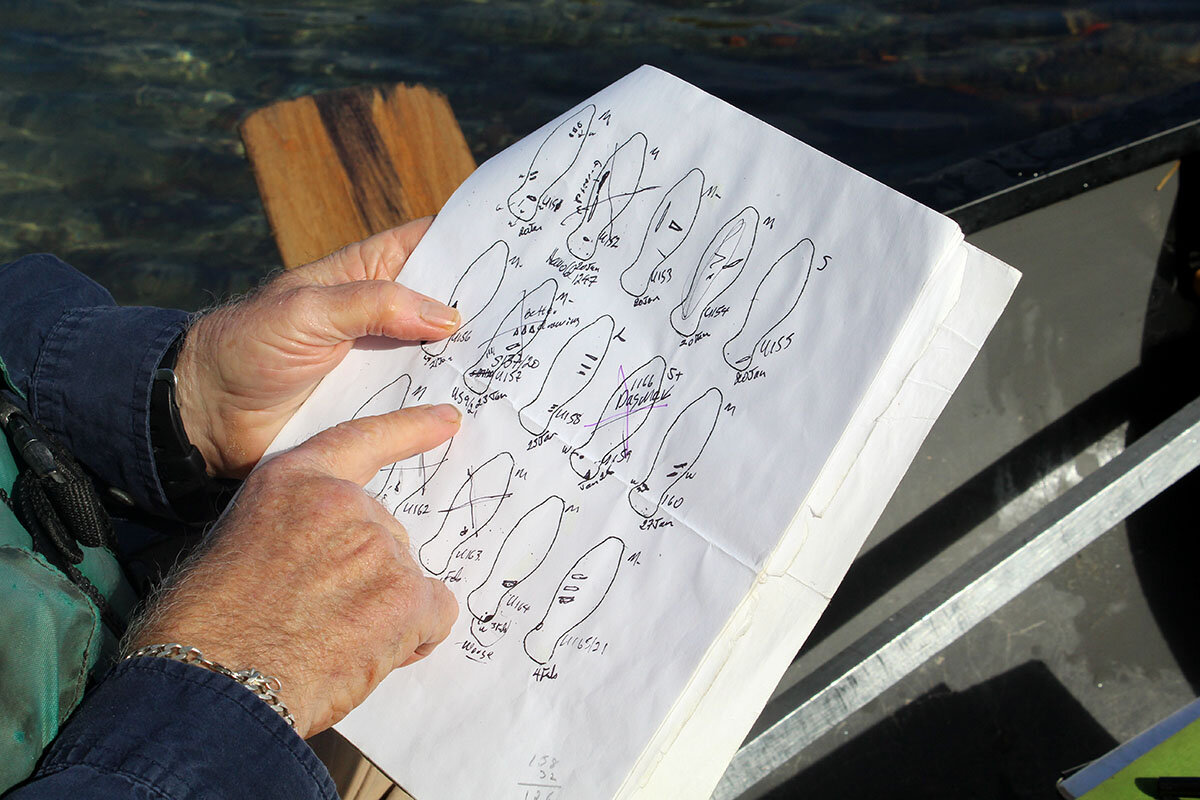

Wildlife specialist Wayne Hartley took notes with a detective’s professional air, a dead manatee at his feet. He nodded his head. Jotted some more.

When he got home, the scribblings were nonsense. “I was upset,” explains the former Army Ranger. Alone in his yard, he threw his cap into the dust. And wept.

That manatee, after all, was an old friend.

Why We Wrote This

When it comes to conservation, human intervention can be a two-edged sword. But efforts to save Florida’s dying manatees suggest a growing need to step in when man-made problems get out of control.

Mr. Hartley, who works for the Save the Manatee Club, first began a daily census of manatees in 1981. At the time, there were only around 36 of the aquatic mammals in Blue Spring State Park, a manatee refuge south of where the St. Johns River, one of the laziest in the world, widens out near the old steamboat town of Palatka, Florida.

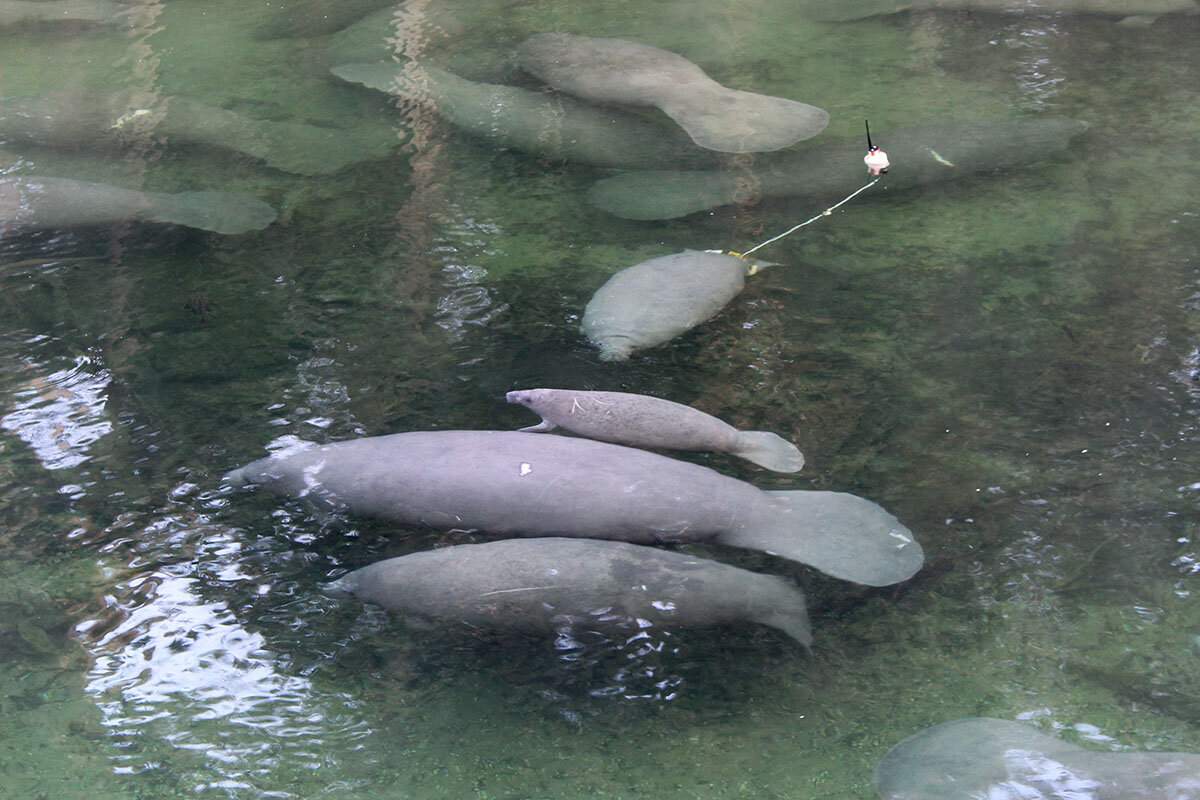

The Blue Spring group boomed to nearly 800 manatees at its peak, says Mr. Hartley. He had to buy a baby name book to keep up. But in the past year, he’s been far busier documenting deaths.

Throughout Florida, state officials counted 1,101 manatee deaths in 2021 out of a total population of between 7,250 and 10,000. The state has already recorded 326 dead manatees this year, as of Feb. 18.

Last year, over half of those deaths occurred in the Indian River Lagoon, a stretch of coastal rivers not far from Blue Spring. Despite efforts to supplement their diets, over a dozen of the animals per week are either starving to death or dying from cold stress as they leave warm water areas in search of food, made scarce because of water pollution.

Mr. Hartley’s job is to match carcasses to known animals, using a collection of drawings and scribbly notebooks – one of the most complete sets of notes on individual wild animals in existence.

An unprecedented effort to feed and rescue dying manatees underscores a precarious balance for one of nature’s most charismatic animals – and an ethical dilemma for humans who must weigh the risks and benefits of intervening to alleviate damage they themselves have caused.

It’s important manatees maintain what philosophers call “wild animal sovereignty” – that they “live flourishing lives ... independently of us,” says Texas A&M University philosophy professor Clare Palmer, in an email.

“There are ethical trade-offs here,” says Professor Palmer, co-author of the upcoming book, “Wildlife Ethics.” “Saving a species may mean a loss of wildness. But it seems likely that conservation is moving into an era where some values will have to be traded off to protect others.”

Resilient but vulnerable

Like humans, manatees are wanderers.

But when winter cold fronts blow in, they gather in large groups in places like Blue Spring, about 30 miles north of Orlando. The water is so clear that schools of 4-pound tilapia and 20-inch snook look like they are swimming in an aquarium. Meanwhile, catfish annoy the massive manatees like mosquitoes.

Wildlife specialist Cora Berchem floats across the water in an Old Town canoe, counting animals.

She has seen manatees battered, bruised, and torn up. Recently, one was stuck in a bicycle tire, earning him the name Schwinn. (The tire eventually came off.) Another is named No-Tail. A badly boat-struck female was set to be euthanized, but managers gave her a last chance by releasing her into Blue Spring. She recovered and now has a calf at her side.

In small and sometimes humorous ways, Ms. Berchem says, she sees the hopes of humanity reflected in the shimmer of Blue Spring.

“They are incredibly resilient – yet so vulnerable,” she says.

Instead of the canary in the coal mine warning of danger, environmentalists say, the manatees are more like the miners.

“They are so much like us in that they have their family bonds, they have their tribes and favorite places and places they like to avoid,” says Jaclyn Lopez, Florida director and a senior attorney for the Center for Biological Diversity, headquartered in Tucson, Arizona. “They are very unique and individual. They are sentient. They can experience pain. And they have feelings – literal, emotional feelings.”

Beyond politics

Susan MacManus grew up in Florida taking family kayaking trips down the Weeki Wachee River, where manatees would playfully bump up against their boats.

Now an emeritus political science professor at the University of South Florida in Tampa, she sees the die-off as part of a Florida paradox, where the economic and political benefits of development and growth have long had a wary coexistence with a profound and often toothy wilderness.

Yet she says the push to stave off more manatee deaths has in some ways risen above Florida’s politics, with popular support for environmental protections – including the 1978 Florida Manatee Sanctuary Act.

“There is strong support for trying to keep the manatee population strong in Florida, and it’s getting harder and harder to do it – for reasons of growth, climate change, and food sources,” says Dr. MacManus. “But there is also sadness and a worry that it’s going to get worse before it gets better – if it does.”

Florida has struggled in recent years with water quality due to large-scale agriculture, residential development, and porous soils that allow septic fields and fertilizer byproducts to run off. Nitrogen-charged water creates algae blooms that killed 46,000 acres – over half – of the seagrass in the Indian River Lagoon in 2021. Those grasses are the manatees’ main food.

Environmental groups, pushing for a long-term solution, filed a lawsuit this month against the United States Fish and Wildlife Service in a bid for stricter water quality standards for manatee habitats – and to hold polluters to account.

“The carnage from 2021 should remove any doubt that Florida’s waters are in crisis,” said Ms. Lopez, the environmental lawyer, in a press release announcing the lawsuit. “The Biden administration needs to act fast to protect manatee habitat[s] from further destruction.”

The decimation has happened so fast that manatees haven’t been able to adapt their behavior.

“Manatees know what they know, and it might take several generations before those that survived the collapse of the Indian River Lagoon pass that knowledge – that institutional knowledge – to their young,” says Ms. Lopez.

Daily feeding

Meanwhile, the public is assisting state and federal wildlife managers in a historic bid to save the struggling Indian River herd. Donors have helped defray the cost of distributing 3,000 pounds of romaine and butter leaf lettuce per day since late January at a feeding station in Brevard County, designed so the animals won’t associate the feeding with humans. Rescues of stressed and emaciated animals are ongoing.

Such interventions are becoming more common in conservation for plants and animals alike. In 2008, volunteers transported 31 seedlings of the disappearing Florida torreya tree to North Carolina. Scientists have begun to gather genetic data on stressed species like Jonah crabs, the black-footed albatross, and narwhals in a nascent bid to genetically modify animals to deal with changing conditions.

“Protecting them matters to us as well as to them,” says Professor Palmer at TAMU.

In four decades of research, this has been Mr. Hartley’s toughest year. Earlier, he saw the species removed from the endangered species list, only to now face possible reinstatement.

But Mr. Hartley is hopeful some of the environmental damage can be reversed. He references dam removal projects where experts thought it would take decades for the environment to rebalance. Instead, it took just years for rivers to revert to natural form.

“Fixing this doesn’t have to take forever,” he says. “Which is why it’s so frustrating that we’re not doing more now.”

Editor’s note: The name of the Save the Manatee Club has been updated.