Next up for the world’s museums: Social responsibility

Loading...

| Nassau, Bahamas

In the days after Hurricane Dorian last fall, the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas (NAGB) in Nassau immediately suspended the temporary exhibition it was preparing and instead asked Bahamian artists to create work that contemplated the storm.

It was part of the museum’s effort to explore “what it means to be a socially responsible institution in the age of climate crisis,” the call for art read. The outcome is “Refuge,” a haunting exhibit on display through March that traces Bahamian experience before and after the storm.

Besides helping the nation heal, the NAGB’s outreach also reflects a changing mindset about the role of museums in sustainability efforts – and issues of the day. Numbering 55,000 globally, according to the International Council of Museums, these trusted institutions have reached a point in their evolution where such participation is both needed and possible, experts say.

Why We Wrote This

Museums have largely become trusted institutions, ones that some say are in a position to step up and help with issues of the day – climate change, community needs. The Bahamas offers a glimpse of what that might look like.

“There’s no other institution like them,” says Robert Janes, founder of the Canadian Coalition of Museums for Climate Justice. “They’re grounded in their communities. And they are at the top of social institutions in terms of how much they’re trusted. Governments aren’t. Corporations aren’t. The media aren’t. But museums still are.” And, he adds, “the lightbulb is going on for a variety of institutions.”

Over the years many museums evolved, says Dr. Janes, from “warehouses of imperial loot” into educational institutions, but ones that occupied a neutral stance. In the past 20 years, a third wave began, he says, where museums have become “malls” and success is measured in visitors and sales from gift stores and restaurants. He argues it’s time for the next phase: social responsibility, community well-being, and even outright activism.

The Bahamas offers an example. Among the works included in “Refuge” is “Everybody and Dey Grammy #hurricanedorian,” a painting by Bahamian artist Christina Wong. It captures the waiting – and overwhelming social media – people dealt with.

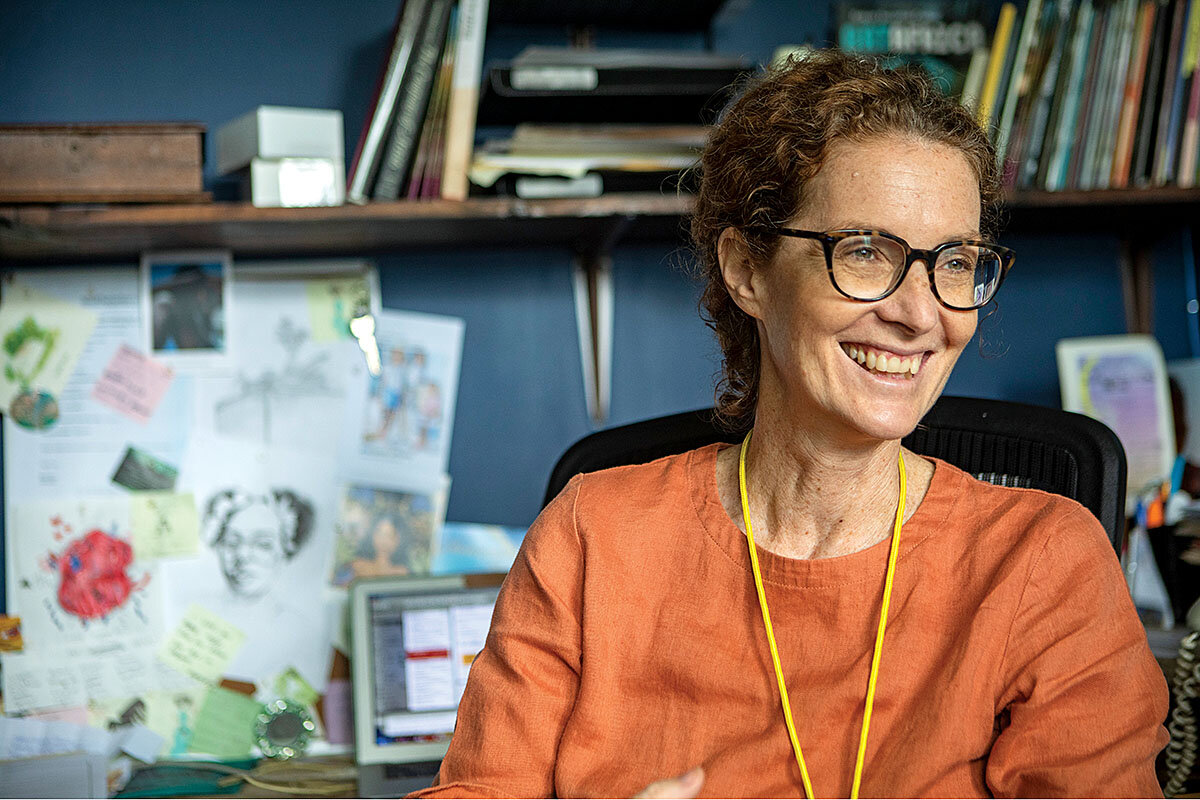

“This was a new thing,” says NAGB executive director Amanda Coulson of the Category 5 storm. “And we have to really rethink all of our actions.”

The Commonwealth Association of Museums, a Canada-based international nongovernmental organization, focuses on encouraging museums in Commonwealth countries, like the Bahamas, to use resources to address the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. That includes everything from indigenous and women’s rights to migration, according to Catherine Cole, secretary-general of CAM.

In some cases, NGOs and activists are creating learning spaces to mobilize the public. Heifer International, which aims to end global hunger and poverty, created Heifer Village in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 2009. There, the public can experience realities in developing countries. We “realized to end hunger and poverty internationally and in our own backyard we must educate the masses about the issues,” says Jessica Ford, who spoke as director of marketing and engagement before leaving the group recently.

Climate change has been a natural subject for museums to tackle as the sense of urgency about global warming has moved from fringe to mainstream. Some of that work includes institutions reviewing their own often heavy carbon footprints, from printed catalogs to traveling exhibits to climate control. A study by Joyce Lee, president of IndigoJLD, concluded that many museums consume as much energy as hospitals.

Today there are museums dedicated exclusively to the subject, like the Climate Museum in New York City, which launched in 2015. Its aim is to “inspire action on the climate crisis with programming across the arts and sciences that deepens understanding, builds connections, and advances just solutions,” the mission statement on its website reads.

Not all institutions have the luxury of contemplation. Hurricane Dorian hit the Abaco Islands on Sept. 1 and then Grand Bahama, decimating entire communities and forcing the evacuation of thousands of survivors. No place was more affected by the influx of people than the dense capital, where resources – and in some cases patience – were strained. The NAGB staff, like all Bahamians, is used to hurricanes – but not of this magnitude. Housed in a pretty yellow mansion on a hill above downtown Nassau, the museum was not physically struck. But part of its immediate relief response turned the institution into a de facto distribution center, with boxes of toiletries and bags brimming with toys stacked in galleries. The museum also sent art supplies to schools whose enrollments swelled with evacuee children, and established art therapy programs.

To date, it has served at least 3,500 survivors and their families. But staff members see a role for the institution long after recovery – and they grasp an opportunity to engage the public in new ways.

“We’re really not doing anything different than we’ve ever done, because the whole point of art is to help people express themselves, to see the world in a different way,” Ms. Coulson says. “It’s just that the hurricane has highlighted why it’s necessary. Because I think maybe six months ago, people were like, does art really help anyone? I think now people are actually beginning to realize, yes, it does.”