From tree spotters to beach brigades: a golden age of citizen science

Loading...

| Rye, N.H.; and Laramie, Wyo.

Wallis Sands State Beach doesn’t lose an inch of sand without this team noticing.

Claudia Gilmartin and Sylvia and Lee Pollock have driven from their homes in Maine to this small beach in Rye, N.H. – their trunks packed with clipboards, neon stakes, and a rope-yardstick measuring apparatus – at least once a month for the past two years.

Each time they visit, Mr. and Ms. Pollock leapfrog the measuring rope down the beach and yell out elevation numbers while Ms. Gilmartin carefully records the measurements.

Why We Wrote This

The push to find productive outlets for political dissatisfaction has spread to the environmentally inclined. Frustrated by the politicization of environmental policy, citizen scientists are taking action.

Gilmartin and the Pollocks aren’t ecosystem specialists. They are retirees turned beach profile monitors, thanks to the Coastal Research Volunteers (CRV) program, a citizen science initiative run by the University of New Hampshire Cooperative Extension and New Hampshire Sea Grant. They plan to produce the first-ever long-term database on erosion and accretion of sand at Wallis Sands.

Across the United States, participation in citizen science is growing. Program coordinators say new technology and phone apps have simplified the data collection process, and the general public now has a better understanding of what “citizen science” means.

But they also cite a new sentiment that has fueled the citizen science movement in the past few years. Dissatisfied with environmental action at the state and federal level, the Wallis Sands team sees citizen science as a form of activism – a concrete way for them to make their own small difference. They may not be able to keep the United States in the Paris climate accord, for example, but citizen scientists from Wyoming to New Hampshire say collecting data for researchers and scientists is a more productive use of their time than ranting on social media.

“It makes you feel a little bit less helpless,” says Ms. Pollock, a clinical psychologist. "I think it reduces people’s sense of not being able to do anything.”

Unlike volunteer or educational opportunities where participants are given a lecture or a particular clean-up task, citizen science projects like the CRV program bring the public into the scientific process. After some initial reluctance, researchers and scientists have come to welcome the extra help in populating datasets, provided that the citizen scientists have adequate training and oversight.

“Global climate change seems overwhelming and impossible… But if I’m doing something and contributing to knowledge, it is an action we can take against some monumental problems that don’t have easy solutions,” says Sarah Kirn, education programs strategist at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute and board member of the Citizen Science Association. “We’re also at a place in our national, political culture where there is some distrust and desire to take things into our hands… There is an interest in transparency.”

A growing corps of citizen scientists

It’s easy to feel like a scientist just by walking into the University of Wyoming Biodiversity Institute in Laramie, Wyo. Art installations of birds hang from the ceiling, and the hallways are lined with glass shelves of fossils and taxidermic animals.

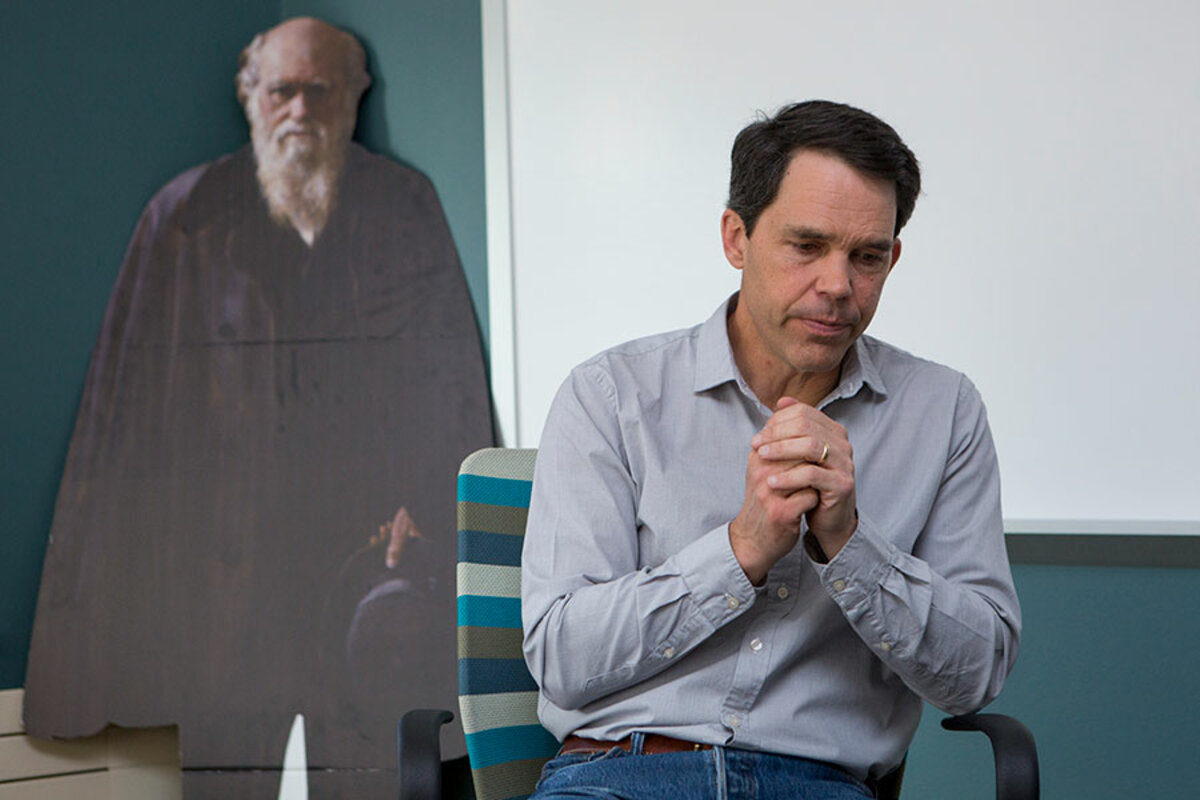

Since its founding in 2012, the Biodiversity Institute has focused on strengthening citizen science in Wyoming through programs such as the Rocky Mountain Amphibian Project, bi-annual Moose Day, and tracking programs for monarchs and freshwater mussels. Earlier this year, the Institute announced a new project to survey the short-eared owl, a notoriously mysterious bird. The Institute asked volunteers to visit the snowy Red Desert before dusk and spend at least 90 minutes looking and listening for signs of the bird.

“That was one where we said: ‘We’ll never get anyone to sign up for this one,’ ” says Institute director Gary Beauvais, laughing. “‘Hey, you get to go out in the middle of the Red Desert and survey for something you're probably not going to see.’ ”

But to his surprise, word of the project spread quickly among serial citizen scientists and all of the slots filled up before the Institute could open registration to the public.

Across the country, program coordinators tell similar stories. Brian Ritter, executive director of the Nahant Marsh Education Center in Davenport, Iowa, hoped 100 people would attend a June “BioBlitz” to document as many living things as possible on the 305-acre reserve. Participation more than doubled his expectation. Danny Schissler, program coordinator for the Tree Spotters program at the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University in Boston, says he has continually increased the number of 3-hour training sessions offered each year since the program was founded four years ago.

And CRV program manager Alyson Eberhardt has been amazed by the dedication of beach profilers who brave New Hampshire beaches in February amid snow and below-zero temperatures. Gilmartin jokes that Ms. Eberhardt should invest in team long-underwear with the CRV logo.

Real science for all?

The majority of program participants are retirees, particularly for time-intensive projects, such as the beach monitoring effort in New Hampshire. Eberhardt hopes to encourage more diverse participation with lower commitment and kid-friendly projects such as horseshoe crab counting and eel monitoring that are more likely to fit into young family and college student schedules.

“When we ask participants what drives them to do this work,” says Eberhardt, “they say they want to give back, learn new things, and meet like-minded people.”

But citizen science is about more than feel-good opportunities for the participants. Amid funding cuts to research at the federal level, and a changing environment posing more scientific questions than ever before, citizen-generated data hold real value for scientists.

The CRV team’s data have already proven useful. Three Nor’easters hit the New Hampshire coast in March, and before the Beach Profile Monitoring program, researchers would not have fully understood the storms’ effects. But because citizen scientists recorded beach elevation levels across the project’s 13 locations before and after the storms, researchers and state officials now have a better idea of which locations need protection during severe storms.

That utility only reinforces the enthusiasm around citizen science programs. When the Pollocks and Gilmartin talk about their work, for example, they are quick to mention the Nor’easter data.

“It ties you into the land,” says Ms. Pollock. “I had never seen anything like what those storms did. It was a jarring awareness. I said, ‘Wow. There is some serious stuff going on here.’ ”

This story was produced with support from the Earth Journalism Network and from an Energy Foundation grant to cover the environment.