Forget Solyndra. Clean energy is hot again.

Loading...

Nearly two years after Solyndra's widely politicized collapse, doubts surround solar and the entire clean-energy industry. Will subsidies survive? Will natural gas put solar out of business? To many investors, the industry seems volatile and risky.

But don't tell that to institutional investors. As they see it, the risks in clean energy have fallen and the industry now provides near bondlike safety coupled with yields near or even above 10 percent. That may explain why major firms, including Goldman Sachs, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, Google, Duke Energy, Bank of America, Kleiner Perkins, Morgan Stanley, Credit Suisse, Rabobank, Wells Fargo, Citi, and Berkshire Hathaway, are pouring money into renewable energy, especially solar and wind.

"Solar is a compelling value proposition," says Nat Kreamer, chief executive officer of Clean Power Finance, a San Francisco-based firm that finances solar projects. Duke Energy, the largest electric power holding company in the United States, announced in June that it was joining other investors using CPF to invest in distributed solar projects that provide reliable rates of return with managed risk.

Or take Goldman Sachs, which is on track to meet its target of providing $40 billion for financing and investing in clean-technology companies over the next decade. In May, it said it will fund $500 million in new projects by SolarCity, a San Mateo, Calif., firm that installs residential and commercial solar energy systems in 14 states. SolarCity has now raised more than $1.6 billion in capital for new solar installations.

So should average investors follow the big guys? Or is it too late to jump in? As of early October, SolarCity (SCTY) stock was up more than 200 percent for the year. Other leading solar energy companies, such as SunPower Corp. (SPWR) and SunEdison Inc. (SUNE), were up 365 percent and 155 percent, respectively.

Analysts are wary. Renewable energy stock prices have soared in the past only to plunge again. Solyndra and other Western solar-cell manufacturers collapsed because of a glut of cheap solar cells from China. Uncertainty over the renewal of clean-energy subsidies has added to the peaks and valleys of investment, because clean-energy companies would struggle without government incentives. An added reason for hesitation: Hydraulic fracturing (fracking) has made natural gas abundant and remarkably cheap, making it tougher for renewables to compete.

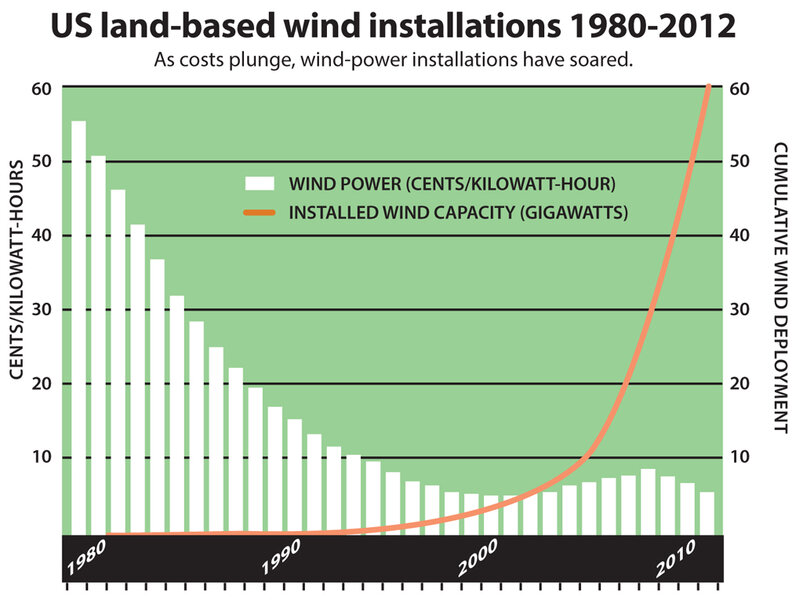

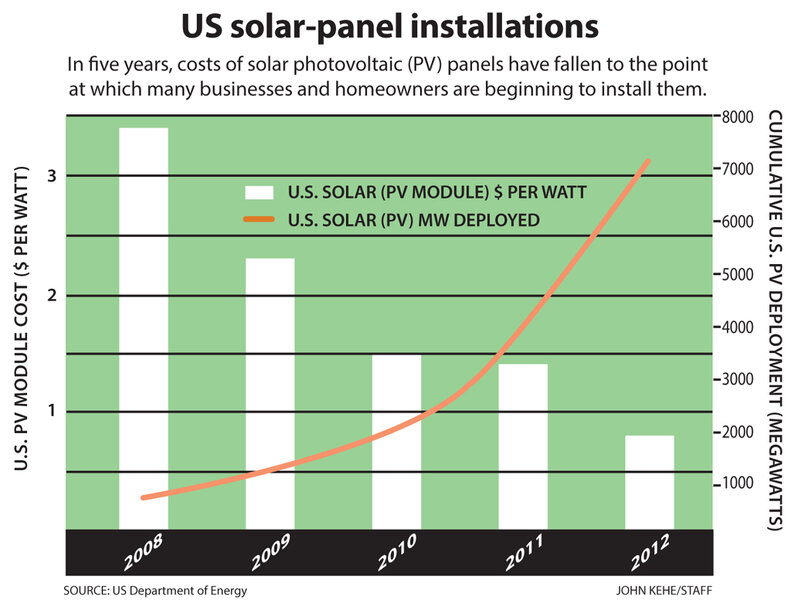

Nevertheless, industry consolidation and steadily rising demand has improved the footing of the best solar industry manufacturers. They expect their margins to keep improving. Then there are all those cheap solar panels.

In the past, "the residential solar industry was effectively a market where wealthy individuals and early adopters who were interested in being environmentally conscious would pay more for getting solar electricity," says Mr. Kreamer. Now, consumers go solar because they are "paying less for solar electricity than they paid in their utility bills."

Since residential solar lowers consumers' electricity costs and since consumers are used to paying their monthly electricity bills, financing rooftop solar installations provides high returns at low risk, he adds. "The massive growth in deployment of renewable energy" gives investors the opportunity to buy "a bondlike instrument with low credit risk and a return that exceeds junk bond returns." He says that as more people learn about clean energy's sound fundamentals and robust growth, more individual investors will reap the handsome returns already flowing to major investors like Google and Goldman Sachs.