In Ecuador's landmark $9 billion judgment against Chevron, all sides unhappy

Loading...

| Quito and Lago Agrio, Ecuador

You might think Humberto Piaguaje would be happy with $9 billion. That's how much the indigenous Secoya of Ecuador's Amazon, along with 30,000 other people represented in a 17-year-old lawsuit, just won from US oil giant Chevron in the biggest environmental judgment in history.

Instead, Mr. Piaguaje was part of a delegation of plaintiffs that lodged an appeal at the Ecuadorean court here in Lago Agrio, saying the Feb. 14 landmark court award is still too small.

"It's a bland victory," Piaguaje, wearing his tribe's traditional red-and-yellow crown, says after leaving the courthouse.

More money is needed, plaintiffs say, to clean up oil contamination from the 1970s and 1980s when Texas company Texaco (acquired in 2001 by Chevron) allegedly dumped 18 billion gallons of toxic wastewater and 17 million gallons of crude oil in this northeastern region, allegedly knowingly polluting an estimated 1,700 square miles of rain forest – an area the size of Rhode Island.

Court ruling sends message

A court-appointed expert originally requested $27 billion in damages for environmental remediation and health care for ongoing health problems.

"Who's going to pay for these losses?" Piaguaje asks. "Chevron has to."

Chevron has also appealed the ruling, calling it "illegitimate and unenforceable." Chevron argues Texaco met all legal obligations when it invested $40 million in government-approved environmental remediation in the 1990s, and furthermore that the court ruling was marred by alleged fraud and corruption.

The legal wrangling is not expected to end soon, meaning that the long-awaited ruling is only one more twist in a 17-year legal drama worthy of a Hollywood film, complete with secret recordings, private investigators, diary excerpts, and beleaguered Amazonians.

But that doesn't mean the verdict isn't rattling the oil industry and exciting environmentalists and human rights activists.

"Regardless of the outcome, it has sent a message to oil and mining companies around the world that just because the government lets you engage in environmentally destructive practices, you're not off the hook permanently," says Robert Percival, a professor of law and director of the Environmental Law Program at the University of Maryland.

Award dwarfs Exxon-Valdez judgment

First filed in New York City in 1993, the lawsuit was moved here in 2003 at the request of Chevron, which has waged an intense defense. The homepage of Chevron.com features an "Ecuador Verdict" section, with the recent headline, "Judgment marred by fraud and misconduct: Get the facts."

Judge Nicolás Zambrano's 188-page ruling says Chevron must pay $8.6 billion, plus 10 percent of the damages (about $860 million) to the plaintiffs, far exceeding the initial $5 billion award against ExxonMobil for the 1989 Alaska oil spill.

Calling the verdict "historic and unprecedented," Amazon Watch and Rainforest Action Network said "[I]t is the first time indigenous people have sued a multinational corporation in the country where the crime was committed and won."

While the court venue – a rundown building in the jungle of Ecuador, a nation with a weak judiciary and widespread corruption – seems to cast doubt on the veracity of the judgment, Professor Percival says he has no reason to doubt its soundness.

Chevron alleges fraud, corruption

Will the award ever be collected? "The plaintiffs are doubtless thinking of enforcing this judgment wherever Chevron has assets, which is just about everywhere," says Ralph Steinhardt, professor of law and international affairs at George Washington University Law School in Washington, D.C. "But most judgment-enforcement regimes have loopholes for judgments won through fraud, which will certainly be Chevron's defense – among others."

Indeed, Chevron complains of alleged government interference in the judiciary, collusion between plaintiffs and a court-appointed expert, and extortion. And this is where the story takes a Hollywood-esque turn.

Chevron on Feb. 1 filed a lawsuit in New York federal court under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) act, using as evidence outtakes from the 2009 documentary "Crude." In one clip, plaintiffs' lawyer Steven Donziger says, "The only language I believe this judge is going to understand is one of pressure, intimidation, humiliation. And that's what we're doing today."

This and other outtakes should be proof of the plaintiffs' attempt to corrupt the court, says James Craig, a spokesman for Chevron. "We have more than a smoking gun, we have a mountain of evidence," he says.

'The real face of this case'

But plaintiffs say Chevron is trying to divert attention from the tragedy in Lago Agrio, where cancer rates are, by some studies, 150 percent higher than in the rest of the country.

On Feb. 7, plaintiffs' lawyers from top Washington firm Patton Boggs filed a lawsuit accusing Chevron of mounting a "smear campaign."

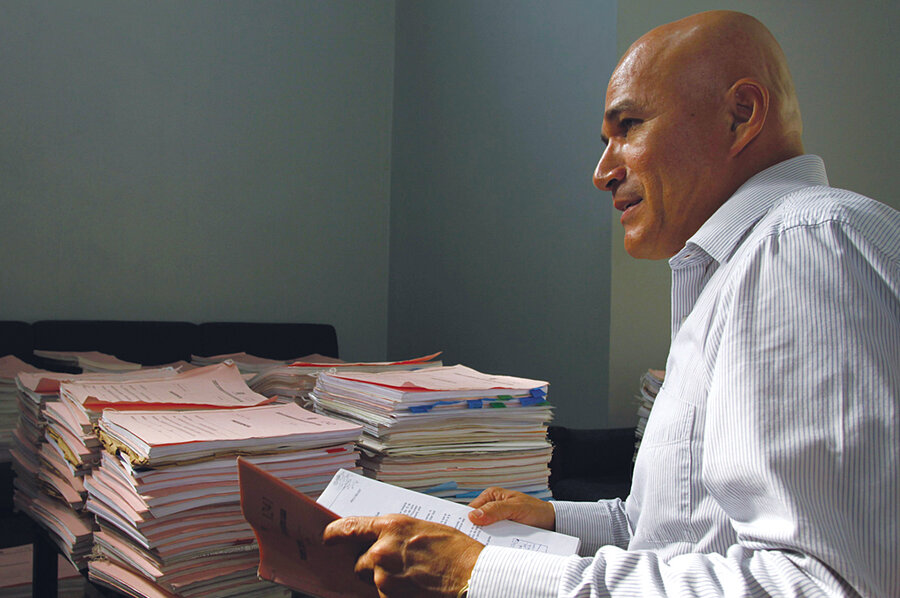

"The real face of this case are people, indigenous people, women, children who are suffering," – but Chevron doesn't want us to talk about that," says lead lawyer Pablo Fajardo.

Piaguaje, the plaintiffs' representative, says five of his family members died of cancer in recent years. Born in 1964, the same year Texaco began operations here, he recalls bathing in rivers that had oil floating on top, and says his feet turned oily black when he walked around barefoot.

"We used to have good shamans that would cure us traditionally," he says. "But the last wise men died of cancer, too."

•With additional reporting by staff writer Stephen Kurczy in Boston.