BP oil seep could spell trouble for containment cap

Loading...

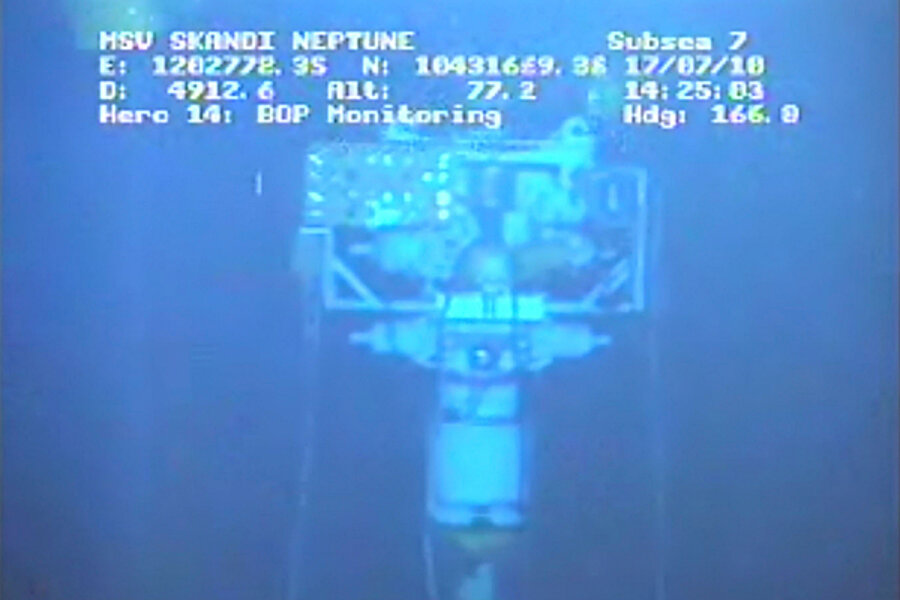

The BP oil seep is a sign of possible danger. But the cap on top of BP’s busted Gulf of Mexico oil well remains shut tight – for now.

On Monday, the US government announced that it was allowing BP to keep valves on the new cap closed despite worries about the newly-discovered seep near the site. That’s a decision that likely will be revisited day-to-day, as federal authorities are still concerned about a worst-case scenario: damage to the sea floor itself.

It’s unknown whether the well casing below the seabed has been cracked. If it has, then the cap could cause leaks to bubble out down below – as if it were a plug in a fizzing pop bottle. This would greatly increase the difficulty of stopping the oil flow.

IN PICTURES: The Gulf oil spill's impact on nature

That’s what the White House wants to avoid. Continued oil flow into August would compound the current environmental disaster, with the November elections looming on the horizon.

“We’re going to be watching this very, very closely, as we have been from the beginning,” said Carol Browner, former head of the EPA and an environmental adviser to the Obama administration, in a Monday interview on CBS.

No oil has flowed from the top of the damaged wellhead into the Gulf since BP installed the cap and closed it late last week. That’s been a bit of rare good news in the long, disappointing struggle against what is likely the worst environmental disaster in US history.

But over the weekend the US and BP seemed at odds over what to do next.

On Saturday, National Incident Commander and Coast Guard Admiral Thad Allen, the top US official on the Gulf response team, said the new cap would eventually be hooked up to pipes to enable oil from the well to be pumped to the surface. But early Sunday BP chief operating officer Doug Suttles said the cap would remain closed until relief wells are completed within the next few weeks.

A few bad signs in recent days indicate it is possible that the well casing below the cap is damaged. Pressure within the well has not risen quite as high as engineers had hoped, meaning there might be a leak down below. And monitoring devices spotted a seep about two miles from the site, according to Ms. Browner.

That is far enough away that it might be a natural seep, as occurs in the Gulf, but close enough that it might also be a sign of damaged well casing.

After an overnight conference call, Allen on Monday announced that he had received adequate information on these problems from BP, and that he was allowing the cap to remain closed for at least another 24 hours.

Allen told BP that when seeps are detected the firm is required to quickly investigate and report its findings to the government within four hours.

“I direct you to provide me a written procedure for opening the choke valves as quickly as possible without damaging the well should hydrocarbon seepage near the well head be confirmed,” wrote Allen in a letter to BP Managing Director Bob Dudley.

Opening the choke valves on the cap could release pressure within the well and prevent further damage. But it could also send oil billowing back into Gulf waters.

BP spokesman Mark Salt said “we continue to work closely with all government scientists on this.”

AP material used in this story.

IN PICTURES: The Gulf oil spill's impact on nature

Related: