Curaçao's crude legacy

Loading...

| WILLEMSTAD, Netherlands Antilles

It’s a scene out of Dante’s “Inferno”: a lake of asphalt and other hydrocarbons stretched out across what was once an estuary of the Caribbean Sea.

From its oil-blackened banks, the fumes are overwhelming, and dead birds can be seen scattered on the gooey surface that, after a heavy rain, can be mistaken for water. The oil refinery that created this lake dominates the skyline, flames pouring from its flare stacks.

“Sometimes dogs and other animals get stuck as well,” environmental activist Yvette Raveneau says of the 200-acre artificial lake that lies on the outskirts of Willemstad on the island of Curaçao.

The lake is just a small part of the environmental legacy of the Isla oil refinery, built in 1918 on this, the largest of the Netherlands’ Caribbean island dependencies. Smokestack emissions still fall on nearby neighborhoods and are blamed for a wide range of health problems. Oil leaks have contaminated the harbor and coral reefs in the nearby sea.

“I am one of the enemies of this lake, but it is not the highest priority,” says Ms. Raveneau, a chemistry teacher and president of Friends of the Earth’s Curaçao branch. Ten years ago, she led the Netherlands’ Queen Beatrix on a tour of this contaminated corner of her kingdom.

“It’s well known that the emissions are much too high, they are hazardous to the health, and yet they go on and on, year after year.”

The refinery blessed and cursed this island of 150,000. Built by Royal Dutch Shell, it provided thousands of jobs and an industrial base for this arid, out-of-the way island and literally fueled the allied invasion of North Africa in World War II. It still employs 900 people and is one of Curaçao’s largest foreign-exchange earners.

“The refinery is a given on the island, and it’s hard to say we would do better without it,” says Don Werdekker, director of the Curaçao Hospitality and Tourism Association. “Some tourist destinations are highly dependent on that one sector, and you can see today how that makes them vulnerable in a crisis. Provided the refinery operates according to the best possible environmental guidelines, we welcome it,” he says.

But Dutch and local authorities never imposed the same environmental regulations they had at home, removing an incentive to invest in pollution-abatement technology. By 1985 the Isla refinery was so antiquated that Shell, Holland’s largest corporation, declared it obsolete. But instead of tearing it down at a cost of hundreds of millions of dollars, Shell got the island government to buy it for $1 and to absolve the conglomerate of any future environmental and health liabilities.

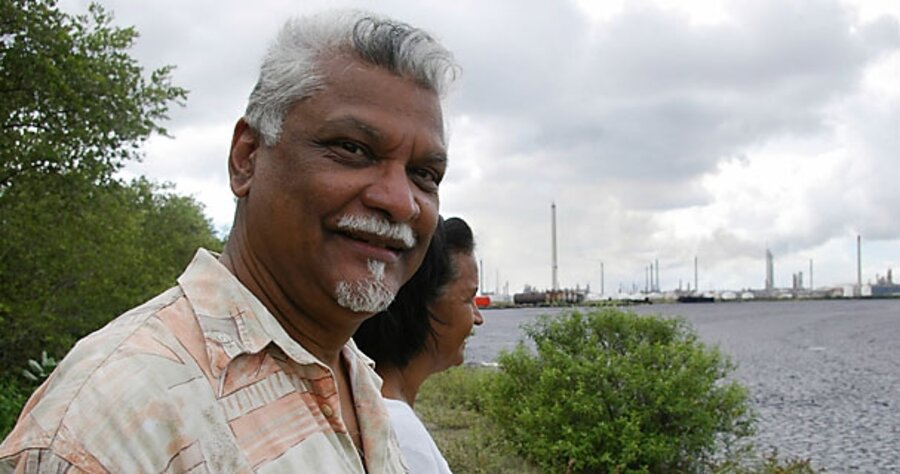

Shell knew that it was getting a sweetheart deal, says Raveneau’s colleague Lloyd Narain, and the island government was naive. “We islanders knew nothing about the refinery – it had been an island within the island – and the government didn’t even have a specialist on their side,” he says. Island leaders panicked when Shell pulled out. They feared social unrest if the plant closed.

Many on the island now think Shell has at least a moral responsibility to clean up past contamination at the refinery, which is currently operated by the Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA on a long-term lease. The international office of Friends of the Earth agrees, and last year held a worldwide campaign to urge Shell to clean up Isla and eight other problematic sites.

“We think Shell headquarters should take responsibility for the problems they have caused in some developing countries,” says Albert ten Kate, a campaigner at the group’s Amsterdam headquarters. “Unfortunately, there hasn’t been much progress.”

Mr. Narain and Raveneau, who have been fighting the refinery since 1989, put overall cleanup costs at $1 billion, a sum far beyond the island’s means.

Shell, based in The Hague, denies responsibility. “As Shell has not had a presence on the island of Curaçao for 23 years and transferred ownership at this time,” a company spokeswoman says, “all liabilities regarding environmental issues have been transferred to the current owner.”

Over the past decade, multinational corporations have come under increasing pressure to assume responsibility for past environmental contamination of sites in the developing world. Chevron is fighting a court case in Ecuador, where it faces potential damages of up to $16.3 billion for the alleged dumping of billions of tons of toxic waste. Friends of the Earth wants Shell to set aside at least $10 billion to clean up oil contamination in Nigeria.

The most pressing problem is the result of current operations: the plume of airborne pollutants. Residents downwind say it triggers headaches, nausea, itchy skin, and respiratory problems. Norbert George, president of the Humane Care Foundation in Willemstad, estimates that more than 12 percent of the island’s population has suffered health damage. Residents say the emissions rapidly corrode metal objects and sometimes stain laundry as it dries on clotheslines.

“In its present condition, [the refinery] poses a health threat to the community and does not agree with the tourism industry of the island,” says the island’s most prominent entrepreneur, Jacob Gelt Dekker, a multimillionaire philanthropist and luxury resort owner. “Local politicians have been unable to make decisions, mostly due to conflicts of interest. Many of them have ties to the plant.”

Humphrey Davelaar, Curaçao’s health commissioner and head of the island’s primary health laboratory, did not respond to requests for comment and official statistics on emissions and health effects. PDVSA’s Caracas-based communications director could not be reached.

A lack of concrete information makes it difficult to assess the refinery’s impact on the marine environment, says Rolf Bak of the Netherlands Institute for Sea Research. “It’s certain that the reefs downstream of the harbor entrance are degraded,” he says. It’s hard to say how much is from the refinery and how much from shipping or elsewhere, he adds.

PDVSA has made improvements, but has been sued in local courts for alleged continued failures to comply with pollution permits. The company has argued that if it were required to comply, it would be forced to close the plant.

“The courts have said they must comply with the permit, but the permit is vague, so the judges can’t tell you a thing,” says activist Narain, who ultimately faults the island’s leadership. “If you don’t have a government that wants to protect the people and really thinks about sustainable development, nothing will happen.”