High stakes in Canada’s vast oil-sands fields

Loading...

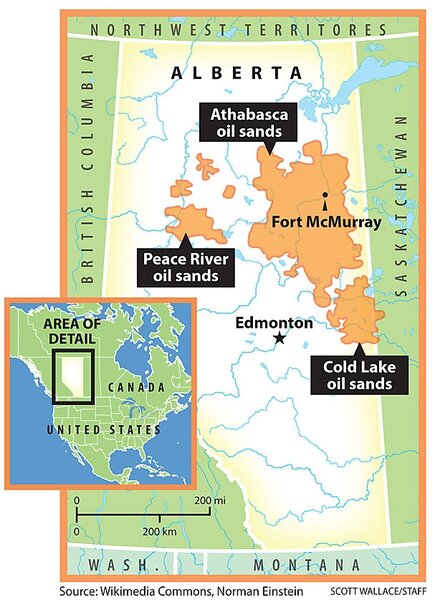

| Fort McMurray, Alberta

The relentless search for oil has led explorers to the boreal forest of northeastern Alberta, among the jack pines and black spruce trees an hour’s drive from the boom town of Fort McMurray. Kelly Hansen, operations manager at ConocoPhillips’s $1 billion Surmont oil-sands plant, holds up the prize: a beaker of sticky black “synbit,” a 50-50 blend of bitumen (a viscous, tarlike petroleum) and synthetic oil.

“The Athabasca oil sands contain the equivalent of 1.7 trillion barrels of oil,” Mr. Hansen says. “About 20 percent of that total can be produced, using current technology” – namely, surface mining and steam extraction underground. Surmont, a facility of gleaming silver-colored steam generators, process pipes, and holding tanks, is jointly owned with French oil company Total. Its initial pilot phase has ended, and the company estimates it will produce 2.5 billion barrels of oil at Surmont.

Thanks largely to the prodigious Athabasca oil sands, Canada ranks second only to Saudi Arabia in terms of total oil reserves. At a time of roller-coaster crude prices and concerns over the security of energy supplies, these oil-sand deposits have attracted more than $100 billion of investment from just about every major oil company in the world.

According to Matt Fox, vice president of oil sands at ConocoPhillips, “Canada represented 20 percent last year of US oil imports. By 2020, it could easily represent 40 percent.”

Athabasca’s oil sands produce a heavy oil. “Upgraders” in the province convert it into a blend of lighter oil so it can enter pipelines and reach markets across Canada and the United States for refining.

Fort McMurray is experiencing a gold rush, even if the gold is black. The two-lane highway into town is often jammed with full-size pickup trucks and prefabricated process plants on wide-load trailers. Life in town is a frenzy of skyrocketing house prices, inadequate municipal infrastructure, mountains of freshly earned cash with little for workers to spend it on, and a huge transient population, much of it in temporary work camps. There’s a severe shortage of skilled labor. Mine workers are being recruited from as far away as South Africa and Venezuela.

Huge environmental footprint

But the biggest concern is the environmental footprint being created by oil-sands development. Extracting Athabasca’s oil is costly not only in terms of infrastructure, but also in water, energy used to produce steam, and the enormous amount of greenhouse gas that results. Some question whether the scale of new projects is wise. At today’s prices, tens of trillions of dollars’ worth of oil are at stake.

The oil sands exist in two formations: Surface deposits account for 20 percent of total recoverable reserves. The rest are at various depths underground.

At Syncrude’s Mildred Lake plant, north of Fort McMurray, giant excavators have scarred the landscape. Like giant otherworldly beetles roaming the moon, 400-ton trucks haul the ore to the extraction plant. Two tons of loose rock and soil and two tons of ore have to be moved to produce a single barrel of oil. Surface mining also uses from 2 to 4-1/2 barrels of water per barrel of oil. The water is pumped from the nearby Athabasca River to produce steam, which helps separate sand and bitumen. Much of the water is recycled, but some is left to settle in highly toxic tailings ponds.

At the same time, Syncrude – a joint venture that includes Canadian Oil Sands Ltd., Imperial Oil (an ExxonMobil subsidiary), Petro-Canada, Nexen, ConocoPhillips, and others – is Canada’s largest single emitter of greenhouse gas, since it must burn 750 cubic feet of natural gas to generate the steam needed to produce a barrel of bitumen. That’s the equivalent of burning one barrel of oil for every eight barrels produced.

According to Steve Gaudet, Syncrude’s manager of environmental services, gradual progress is being made to reclaim land at mined sites by replacing topsoil and replanting shrubs and boreal forest trees. More than 20 percent of the Mildred Lake site has been reclaimed, he says, but desertlike areas remain.

In terms of water use, Mr. Gaudet says Syncrude uses 0.2 percent of the annual flow rate of the Athabasca River. “At the lowest flow rates, during the winter, we use 0.5 percent,” he notes. With the planned expansion, that figure will rise to 1 percent. (Some 60 percent of Alberta’s Bow River flow is exploited by cities like Calgary, as well as by agriculture and industry.)

Some aboriginal communities downstream are worried that contaminated water will seep back into the river and affect the drinking water and fish they depend on. This fall, the Alberta government is due to release a long-awaited report on the impact of oil-sands wastes on public health in the communities.

As surface mines of bitumen ore are gradually depleted, in situ (subsurface) extraction facilities like Surmont are springing up across the northern forest, connected to Alberta’s pipeline grid. They seem environmentally friendlier.

“Surmont is built on swampy muskeg,” Mr. Hansen of ConocoPhillips notes, “so clay had to be hauled in, and piles had to be driven into it to stabilize the plant.” In this particular area, the bitumen reservoir is 1,200 feet underground. “Drawing on a saline aquifer 650 feet down,” Hansen explains, “we inject steam through one well bore, and the steam gives the bitumen the consistency of cream. The bitumen then gravity-drains to a producer well. Once we stop injecting steam, it condenses to water and we recover emulsion, which is the combination of bitumen and water.” Most water is recycled, he says, and waste water is reinjected into the earth below the saline aquifer.

Steam extraction less resource-heavy

Compared with surface mining, this method uses far less water – 1/4 barrel of water per barrel of oil. But for both kinds of extraction, greenhouse gas created by steam generation remain a huge challenge. Even if emissions per barrel decline, oil production is growing rapidly. ConocoPhillips is considering ways to store carbon underground and find alternatives to natural gas to fire the plant.

ConocoPhillips is the biggest landholder in the Athabasca oil sands, with leases on 1 million acres. The company forecasts production of 1 million barrels per day at facilities like Surmont over the next two or three decades. “We know the resource is there,” says Mr. Fox, an oil-industry veteran from Scotland. “The pace of development will be dictated by economics and available technologies.”

The ferocious rate of government approval of new projects is upsetting some Canadian politicians as well as environmental groups from the World Wildlife Fund to the Sierra Club.

Former Alberta premier Peter Lougheed is called “father of the oil sands,” since he was such a big factor in starting development in the 1970s and ’80s. But in a speech in August 2007, he warned that Alberta’s practice of bypassing federal environmental laws in its race to approve oil-sands projects “will cause significant stress to Canadian unity…. The government of Alberta, with its acceleration of oil-sands operations, will in my judgment be seen as the major villain in all of this in the eyes of the public across Canada.”

“Who can say ‘no’ to this much oil?” asks Simon Dyer, oil sands program director at the Pembina Institute, a Calgary-based sustainable-energy advocacy group that also consults for the government, aboriginal communities, and the oil industry. “The debate on the pace and scale of development isn’t being held in government. It is irresponsible to approve so many projects without protecting 20 to 40 percent of the environment in northeast Alberta – permanently. Both federal and provincial governments have failed to set limits on oil-sands production, for example, by placing a hard cap on water use of the Athabasca River and tightening rules for land-use reclamation.”

Very weak greenhouse-gas targets

“We have hopelessly weak greenhouse-gas [GHG] targets in Canada,” adds Mr. Dyer. “If you look at Canada’s total projected increase of GHG from 2003 to 2010, 41 to 47 percent of Canada’s increase can be attributed to the oil sands. They are the one single issue dragging us away from reducing GHG emissions.”

In August, the Pembina Institute pulled out of the multistakeholder oil-sands process, citing the lack of credible environmental management the last eight years.

Pembina’s Dyer acknowledges that there has been some progress in the environmental footprint per barrel of oil produced. But the phenomenal rise of oil-sands production will create enormous environmental problems, he says. “Would environmentally friendly measures cost the oil industry more? No one has done a real study of the costs of oil-sands production in terms of mitigation for the environment.”