Midocean trawlers mine world’s seamounts

Loading...

| New York

In the mid-1970s, fishing boats came across great aggregations of a reddish fish around underwater mountains, called seamounts, near New Zealand, a kilometer deep. A century before, fishermen had discovered the same species in the northeast Atlantic. But never had anyone encountered schools this dense. Characterized by a blunt face lined with mucosal glands, the fish wasn’t exactly handsome. But its flesh, which tasted vaguely of shrimp, was white, firm, and delicate. The only problem: the name. The fish was called “slimehead.” So “some smart marketer,” in the words of one expert, rechristened it “orange roughy.” And a new high-end fishery was born.

For many, it was evidence of a worrisome new trend. Enabled by improved technology, fishing fleets were going farther and deeper than ever before. By the mid-1980s, they had converged on seamounts the world over, seeking deep-water species like orange roughy and Patagonian toothfish (marketed as “Chilean sea bass”). They were now trawling places that, by virtue of their depth and rough topography, were previously off-limits. Many characterize what followed – and continues to occur – as akin to strip-mining: Catch everything as quickly as possible and then move on. Scientists worry that these deep-sea ecosystems populated by long-lived organisms can’t withstand the fishing pressure. But there’s little recourse: Many of the estimated 30,000 seamounts worldwide lie outside national jurisdiction, and the high seas remain unregulated.

Conservationists have long lobbied for regulating international waters. In recent years, the effort has borne fruit in the form of nonbinding agreements. But some, doubting the efficacy of nonenforceable pacts, think high fuel costs are the high seas’ best hope. When it’s too costly to fish the mid-Pacific, fishing vessels won’t go there. But for now, as seamount trawling continues in much of the world, scientists fret that these unique ecosystems may disappear before they can find out what’s there.

“They’re the least-explored mountains on the planet,” says Elliott Norse, president of the Marine Conservation Biology Institute in Bellevue, Wash. “We know more about Everest than the seamounts.”

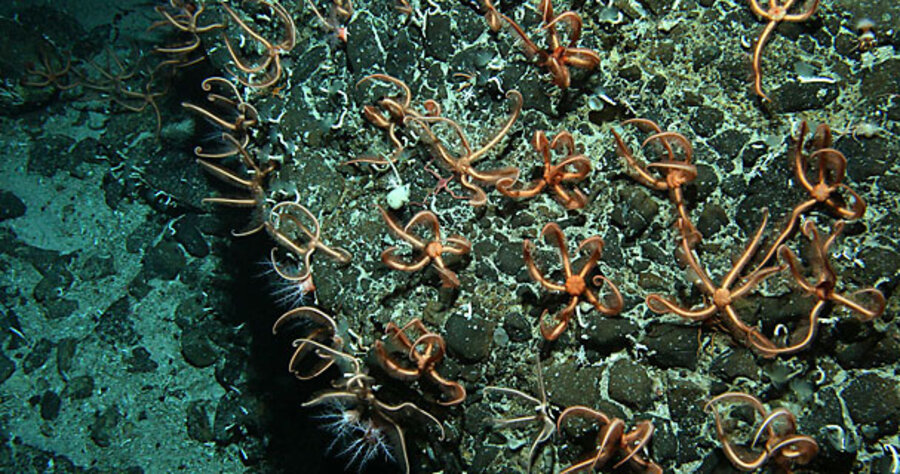

Underwater mountains obstruct ocean currents, forcing deep, nutrient-bearing water upward. So seamount ecosystems are fertile compared with the surrounding ocean, and they support unique organisms. Many of them have adapted to the cold, dark conditions with slow growth and long lives. Orange roughy, which reach sexual maturity at between 20 and 30 years of age, can live to be 150.

Some deep-sea corals have been dated to 4,000 years old. They were growing when Moses led the Israelites out of Egypt, says Mr. Norse.

Scientists think that many seamount species are endemic, existing only there. One survey near Tasmania found that perhaps one-third of the invertebrates were endemic. Between 24 and 43 percent were new to science. Researchers have also found that seamounts closed to trawling had double the biomass and nearly half again as many species compared with those that were trawled. The high rate of unique species, plus the ecosystem’s sensitivity to disturbance, leads many to conclude that seamount trawling will lead to extinctions.

“To simply remove species from the planet, particularly on a large scale, is something we can’t go back on,” says Tony Koslow, a deep-sea ecologist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif., and lead scientist on the Tasmania surveys. “It’s just ethically wrong if it can be avoided.”

Soviet ships were the first to fish seamounts when, in the late 1960s, they stumbled across large schools of armorhead along the Emperor Seamounts northwest of Hawaii. Less than a decade later, Soviet and Japanese fleets had harvested 1 million metric tons of armorhead. The stocks have yet to recover.

“They just hammered these series of seamounts,” says Dr. Koslow. “Once they wiped out the armorhead, they then began searching somewhere else.”

Some say that fishing seamounts on the high seas is inherently unsustainable. The cost of motoring long distances and dragging nets set a mile deep forces vessels to take as much as they can quickly, and then move on.

“You’re basically talking about mining and liquidation as an economic model,” says Michael Hirshfield, chief scientist of Oceana in Washington, D.C. “You’ve got the potential for a sustainable fishery, but it’s not going to be at a rate of return that pays for your big powered vessel.”

Subsidies, perhaps equal to one-quarter of an $80 billion global industry, are what make high-seas fishing profitable at all, says Les Watling, a professor of zoology at the University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

“Basically, if there were no subsidies, these guys wouldn’t be able to afford the fuel to go out there,” he says.

But, pointing to the many “pirate” vessels that fish profitably without government aid, Koslow says subsidies can’t be blamed for all seamount ills. Indeed, where orange roughy populations fall within national jurisdiction – and therefore relatively near shore – they’ve still plummeted. In 2006, Australia put orange roughy on its endangered species list, the nation’s first commercially exploited fish to earn that distinction.

New Zealand, meanwhile, has been ratcheting down its allowable catch for the past 20 years. Now at a low of 13,082 tons, it’s just one-quarter of its 1989 peak. Half the orange roughy stocks surveyed in a 2003 World Wildlife Fund report were at 30 percent of their prefishing biomass. (The rest was unknown.)

“We’re not feeding the starving with orange roughy or Patagonian toothfish,” says Peter Auster, science director with the National Undersea Research Center in Groton, Conn. “A good percentage of this fish is for US and European markets.” New Zealand, the world’s largest roughy producer, exports more than 60 percent of its catch to the United States, the world’s largest roughy consumer.

Only a few countries trawl seamounts in international waters, perhaps 13 in all including Russia, Japan, and Spain, says John Hocevar, an oceans specialist with Greenpeace. (While the US fleet fishes the high seas for open-water species like tuna, it has no seamount fleet.) The concentrated nature of the seamount fleet gives Dr. Hocevar reason to hope.

“If those countries bought into protection, then they can quite easily monitor and enforce vessels,” he says. "These are wealthy, technologically capable countries."

The same GPS technology that lets high-seas fleets fish the ocean’s vast expanses enables monitoring that would have been impossible 15 years ago. “Pretty much every ship ... is on somebody’s satellite,” says Dr. Hirshfield.

The bottom line: High-seas fishing will continue “as long as there’s a market,” says Professor Watling. But he’s not without hope. High fuel prices are eating into profit margins. If they keep rising, high-seas fishing may end naturally.

“We’ve been waiting for a few years for something like this to happen,” he says. “We all knew that eventually fuel prices would go up.”