Researchers race to save Alaska’s coral gardens

Loading...

| Anchorage, Alaska

To German naturalist Georg Steller, who accompanied explorer Vitus Bering on his 1741-42 voyage of discovery commissioned by Russia’s Peter the Great, the treeless islands that arc between mainland Siberia and North America were treasure troves of new plants, animals, and geology.

“I encountered wondrously strange views that at first glance were more like the ruins of large cities and edifices than a chance display of nature,” Mr. Steller wrote in his journal.

Nearly three centuries later, researchers continue to make new discoveries about the remote Aleutian archipelago that stretches more than 1,000 miles from the Alaska mainland.

Regular surveys of the Aleutian waters, such as the biannual trawl surveys by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, consistently turn up previously unknown life forms.

“It isn’t like the dark side of the moon or anything,” says Mark Wilkins, supervising research fishery biologist at NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center in Seattle. Still, “it is relatively new in terms of being looked at carefully by biologically trained people.”

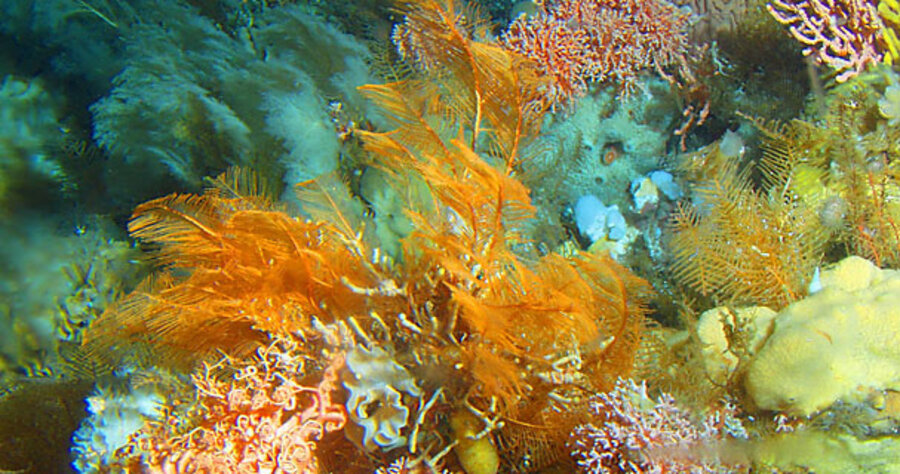

One of the most significant finds of recent years was the vast cold-water coral gardens on the floor of the sea shelf, 300 to 1,000 feet down. Scientists and fishermen had long known that corals grew here – grayish pieces had turned up in fishing gear. But it was not until 2002, when a pair of NOAA scientists plunged down to the site in a tiny two-person submarine, that anyone knew of the corals’ diversity and vivid hues.

“You turn on the lights, and it was just amazing,” says Jon Heifetz, a Juneau, Alaska-based NOAA scientist who was one of the two in the sub. “Every single inch of rock was covered with colorful corals and sponges.” No sunlight penetrates this deep.

The discovery prompted federal fishery managers in 2006 to ban bottom-scraping trawl harvests in nearly all the Aleutians, along with other spots in the Gulf of Alaska. The ban, protecting about 379,000 square miles, was hailed as a milestone.

“It was clear that this was a treasure that we needed to protect,” says John Warrenchuk, a Juneau-based scientist with Oceana, an environmental group that worked for the ban. There was industry resistance, but it was overcome by public sentiment to preserve this “habitat that we’ve seen nowhere else in the world,” Mr. Warrenchuk says.

The campaign was helped by the fact that the decision did not eject bottom trawlers from grounds they were already using. “They were losing future opportunities, but the most productive fishing grounds were left open,” he says.

Other discoveries here in recent years include two potential new species of “walking” or “swimming” sea anemones that move across the seafloor instead of being anchored to it; a new type of kelp that scientists have named “golden V” because of its color and shape, and several new types of bottom-dwelling fish.

With an eye to the continuing biological mysteries of the Aleutians, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, which sets policy for commercial fishing in federal waters off Alaska, has launched a pilot program to manage and monitor the region as an integrated and unique ecosystem. The plan, started last year, considers not just stocks of commercially valuable fish but also marine mammals, changing climate conditions, nonfishing human activities (including military operations, shipping, potential oil and gas exploration), and a host of other factors.