• Cable sabotage: Finnish investigators probing the damage to a Baltic Sea power cable and several data cables say they have found an anchor drag mark on the seabed, apparently from a Russia-linked vessel that has already been seized.

• Ukraine funding: President Joe Biden announced nearly $6 billion in additional military and budget assistance. He is surging aid to Kyiv before he steps down.

• E. Jean Carroll award upheld: The 2nd United States Circuit Court of Appeals issued an opinion upholding both a Manhattan jury’s finding that Donald Trump sexually abused Ms. Carroll in a department store dressing room in the 1990s and its $5 million award to Ms. Carroll.

• Plane crash investigation: South Korean officials announced plans to conduct safety inspections of all Boeing 737-800 aircraft operated by the country’s airlines, and to conduct an emergency review of aircraft operation systems.

• Trump backs H-1B visa: President-elect Donald Trump sided with billionaire supporter Elon Musk in a public dispute over the use of the visa program, saying over the weekend that he supports the program for foreign tech workers.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

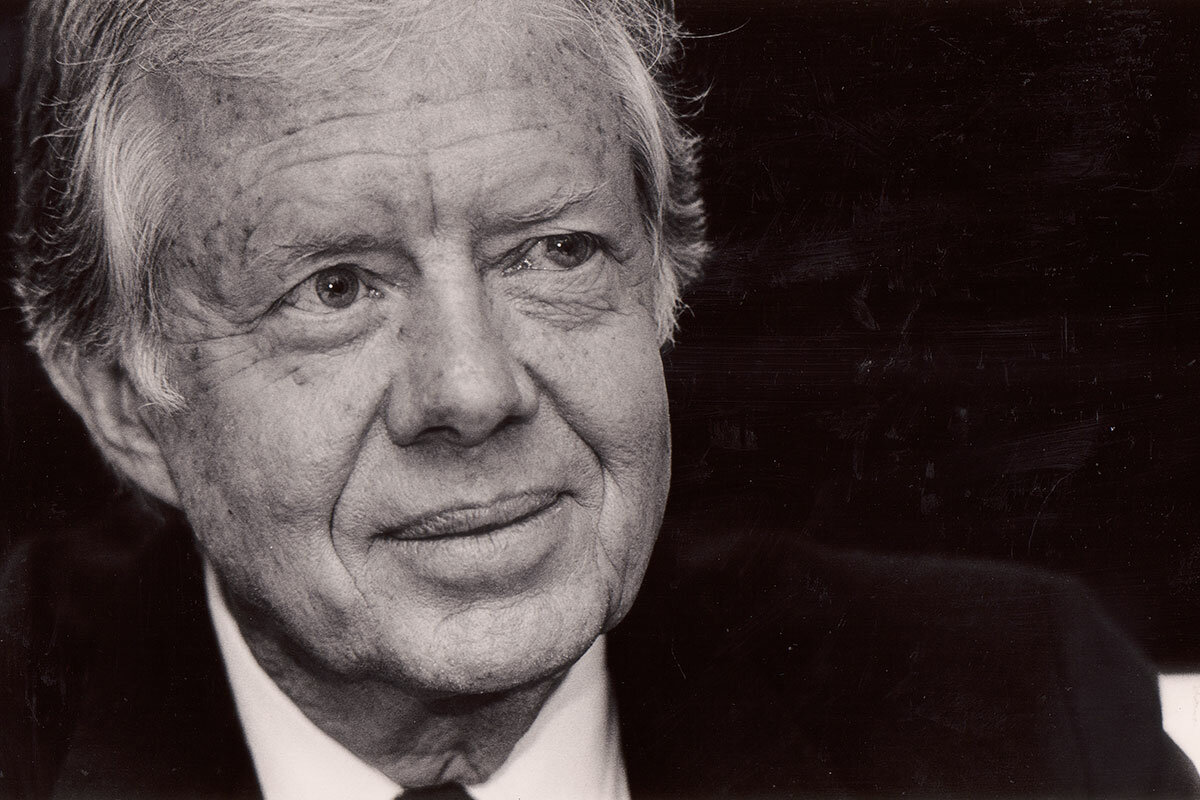

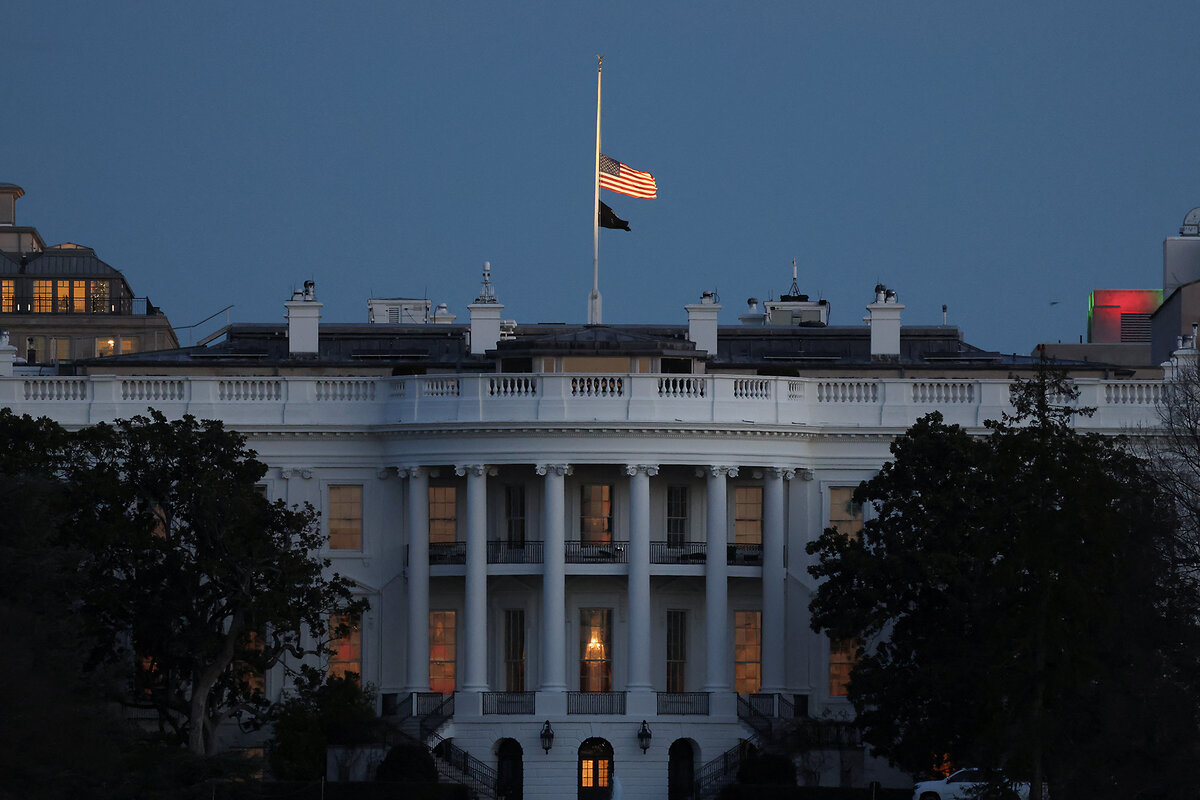

Today’s Daily starts with a case study in a life of service: to God, to neighbors and strangers alike, to country and the world, to family. You may have read other tributes to the late U.S. President Jimmy Carter, but spend a moment with Harry Bruinius’ rich appreciation of a “roving peacemaker”: a man who admitted he was a better ex-president than president, who acknowledged missteps and worked to course-correct, and, of course, who strove to center his life on a faith lived actively and compassionately.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

News briefs

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 12 min. read )

Throughout his life, President Jimmy Carter would define his faith as “inextricably entwined with the political principles I have adopted.” It would infuse the decisions he made at every stage of his career as a public servant in ways both good and bad, historians say.

( 6 min. read )

On nine different visits to our Breakfast table, over the course of many decades, the former president displayed his keen intellect and trademark decency. He also made news.

( 5 min. read )

For more than a year, Yemen’s Houthi rebels have launched long-distance missile and drone attacks on Israel and Red Sea shipping. After Israel largely subdued its Iran-allied enemies closer at hand, it is struggling to deter the Houthis on its own.

( 5 min. read )

In Mexico, attitudes toward migration have not been overwhelmingly polarizing. But some worry that acceptance could wane amid a wave of deportations.

( 7 min. read )

Who is responsible for the health of young people? Tobacco bans in Massachusetts towns have residents weighing public health concerns against individual freedoms and considering what it means to have a “nicotine-free generation.”

Books

( 7 min. read )

We asked our reviewers to choose the books that captured their imaginations this year. They came back with thoughtful and eclectic titles that speak to our common humanity.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

More than 1.5 billion ballots were cast in elections in 73 countries in 2024. If the upshot of that global democracy "supercycle" can be captured in a single comment, it is this: “When you are in [power],” Pelonthle Ditshotlo, a voter in Botswana, told The Africa Report, “we need to know that you listen to us, you are with us.”

A year that started with concerns about whether democracy was losing ground to more repressive forms of governance has instead revealed a different mood – not for less democracy, but for democracy that is more effective and accountable. Voters tossed out more incumbents than ever before. Dictatorships fell. A new generation of leaders emerged.

The result may be a global turn toward more humility in governing. In South Africa and India, powerful political parties were forced into ruling coalitions. “What this election has made plain is that the people of South Africa expect their leaders to work together to meet their needs,” President Cyril Ramaphosa said after his ruling party, the African National Congress, lost its singular hold on power in June after 30 years.

In neighboring Botswana, President Mokgweetsi Masisi said, “We got it wrong [and] I will respectfully step aside,” after voters ended his party’s 58-year monopoly on power.

“The reality is that in a democracy, the people have the final say,” said Lai Ching-te, Taiwan’s new president, in his inaugural address on May 20, 2024. “I will strive to prove myself as someone in whom you can trust and count on, by acting justly, showing mercy, and being humble, and by treating our people as family.”

Even in countries where democracy is a fragile aspiration, leaders have felt a need to soften their hard lines. Upon winning the presidency in Iran in June, Masoud Pezeshkian spoke from the Mausoleum of Ruhollah Khomeini in Tehran. Although he was there to “renew his loyalty” to the founder of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, he nonetheless promised voters, “I will listen to your voices.”

Humble governing may be a key to rebuilding broken nations. Local elections in Libya in November marked the first step in a tentative process to unite the North African country after more than a decade of divided rule and conflict. The ballot drew participation from 74% of voters. That prompted the head of the transitional presidential council, Mohammed Menfi, to acknowledge “the importance of resorting to the opinion of the Libyan people” in rebuilding democracy, The Libya Observer reported.

“By promoting a culture of listening at all levels of society, including the government, media, educational institutions, and the citizenry, we can hope to bridge political divides and move towards a more united and harmonious future,” wrote Guaiqiong Li and Rainer Ebert, Africa experts at Yunnan University and Rice University, respectively, in the Cape Argus, a South African newspaper, on Monday.

Dozens of countries will hold elections in 2025. Their voters may note the work already done in renewing democracy through humble listening.

Editor's note: This editorial was updated to reflect the correct date of the inaugural address of Taiwan's new president.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 1 min. read )

God’s harmony is for every moment, every place, as this poem conveys.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, New Year’s Eve, we’ll treat you to a special issue of our photographers’ favorite photos of 2024. The Daily is off New Year’s Day, and then we pick up again Jan. 2.

And finally: What would a pending new year be without reflections on resolutions? Read one writer’s thoughts about how he honored some early-in-the-year vows for more than a month or two.