President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump will have different mandates on Thursday, strategists say. Mr. Biden will want to show vigor and stamina, while Mr. Trump will want to demonstrate he can be serious and statesmanlike.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

With the Olympics around the corner, we thought we’d announce two new bronze medals for The Christian Science Monitor.

The Society for Features Journalism might not be the Olympics of journalism, but it’s close. The competition had more than 1,000 entries this year, with the Monitor competing against The New York Times, The Washington Post, and others.

We took two third-place prizes, one for our Climate Generation series, and another for our weekly “Why We Wrote This” podcast. The judges called our entries “colorful,” “impressive,” and “fun.” When the people who know the craft recognize your work, it’s a wonderful boost.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 5 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Bolivia coup attempt: Armored vehicles rammed into the doors of Bolivia’s government palace Wednesday in what appeared to be a failed coup attempt.

• Denmark climate tax: Denmark will tax livestock farmers for the greenhouse gases emitted by their cows, sheep, and pigs in 2030, the first country in the world to do so.

• Biden pardons: President Joe Biden pardons potentially thousands of former U.S. service members convicted of violating a now-repealed military ban on consensual gay sex.

• Hollywood union deal: The union that represents most behind-the-scenes film and television crews reaches a tentative deal with studios for about 50,000 of its members, making another production-stopping strike unlikely.

• Democratic primary: George Latimer has defeated U.S. Rep. Jamaal Bowman of New York in a Democratic primary that highlighted the party’s deep divisions over the war in Gaza. Mr. Bowman has accused Israel of genocide in Gaza.

( 5 min. read )

Can the federal government crack down on misinformation online without stomping on the First Amendment? That’s just one hard question that remains unresolved after Wednesday’s Supreme Court ruling.

( 6 min. read )

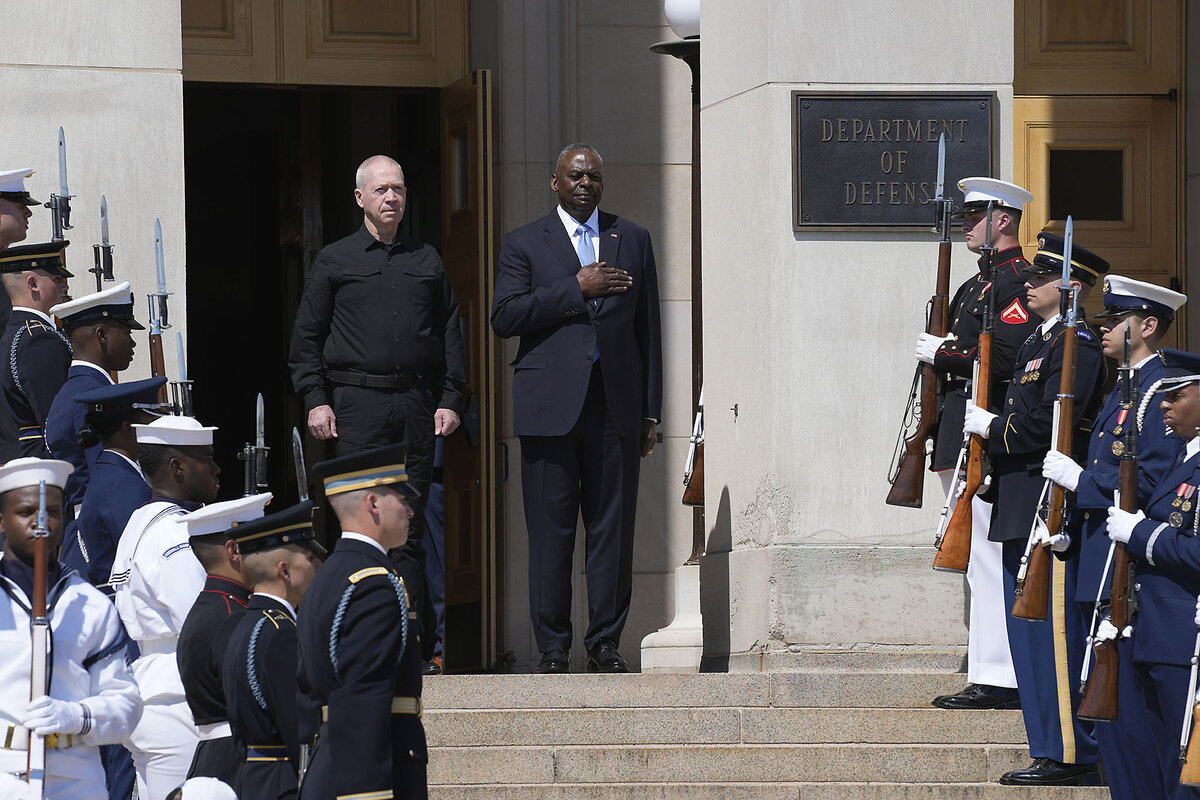

Many factors fuel resilience in time of war: hope, confidence, unity, trust in government. As Israelis endure their longest-ever war, against Hamas in Gaza, the threat of a far more arduous conflict looms with Lebanon’s powerful Hezbollah.

( 3 min. read )

Russia stamped out domestic terrorism 20 years ago, after a violent campaign in the Caucasus. But ethnic and religious tensions appear to be rising again amid wars in Gaza and Ukraine – and with them, worries about extremist terrorism.

( 4 min. read )

What’s lost in a society that prizes productivity and efficiency? The sweetest moments are found when we slow down, pause, and take a moment to connect with loved ones.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

Charitable giving by individual Americans took a dip last year, largely because of worries over inflation, according to the latest Giving USA report. Yet the report also notes an unexpected shift. Giving for basic needs such as food or housing has risen for four years despite economic changes. Such giving for “human services” now ranks second to donations for religious institutions, edging out giving for education.

One reason may be that Americans are trying different ways to be generous without relying on established charities. One popular avenue in recent years has been “giving circles.” These are small groups of individuals who gather to seek out local needs and then pool money to meet those needs.

Search almost any local newspaper and you might find a headline like this recent one in Ashland County, Ohio: “County to benefit from EmpowHer Giving Circle.” Donors in that group are asked to give only $75 or less to a cause.

The growth of giving circles has been explosive. Their numbers have risen from roughly 1,600 seven years ago to nearly 4,000 last year. Their total giving has jumped from $1.29 billion to more than $3.1 billion, according to a report in April by Philanthropy Together.

The report found that 77% of people in a collective giving group say their participation gave them a “feeling that their voices mattered on social issues.” The report attributes such results to five “T’s”: time, treasure, talent, ties, and testimony.

This sort of bottom-up philanthropy relies heavily on trust, equality, and selflessness; a virtuous circle that draws in more individuals who see the inherent worth of those in need in a community. Giving circles are also “schools of democracy,” as the report puts it. Participants must often listen to and learn from those who hold opposite views on social problems.

The report predicts that the number of giving circles will double in the next five years. “We are a force, and a joyous force,” Isis Krause, Philanthropy Together’s chief strategy officer, told Inside Philanthropy. New ways of giving are not only creating new ways of gathering. They are also pointing to higher concepts of joy.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 4 min. read )

Each of us can nurture an understanding of God’s universe as harmonious and good, which ripples out to bless us and the world around us.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

We’re so glad you could join us today. We hope you’ll come back tomorrow when Simon Montlake looks at why some diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts are faltering on campuses and in boardrooms.