Immigration and the economy are top concerns of voters ahead of the 2024 U.S. election. But political talking points don’t tell the whole story.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Amelia Newcomb

Amelia Newcomb

Do wonder and hope belong in the news?

Wonder certainly did yesterday, as Americans marveled at the total solar eclipse sweeping across their country. It challenged the discordant images many Americans hold of each other. Staff writer Simon Montlake reflects today on experiencing it with his son.

You’ll see hope in our other stories as well. In Antakya, Turkey, a school principal is countering expectations of a “lost generation” struggling in the aftermath of last year’s devastating earthquake. And amid National Poetry Month, a former U.S. poet laureate, no stranger to hardship, talks about looking for the stars – the “constellation of story” that helps a person thrive.

Building trust in the future, looking for light. It’s news.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

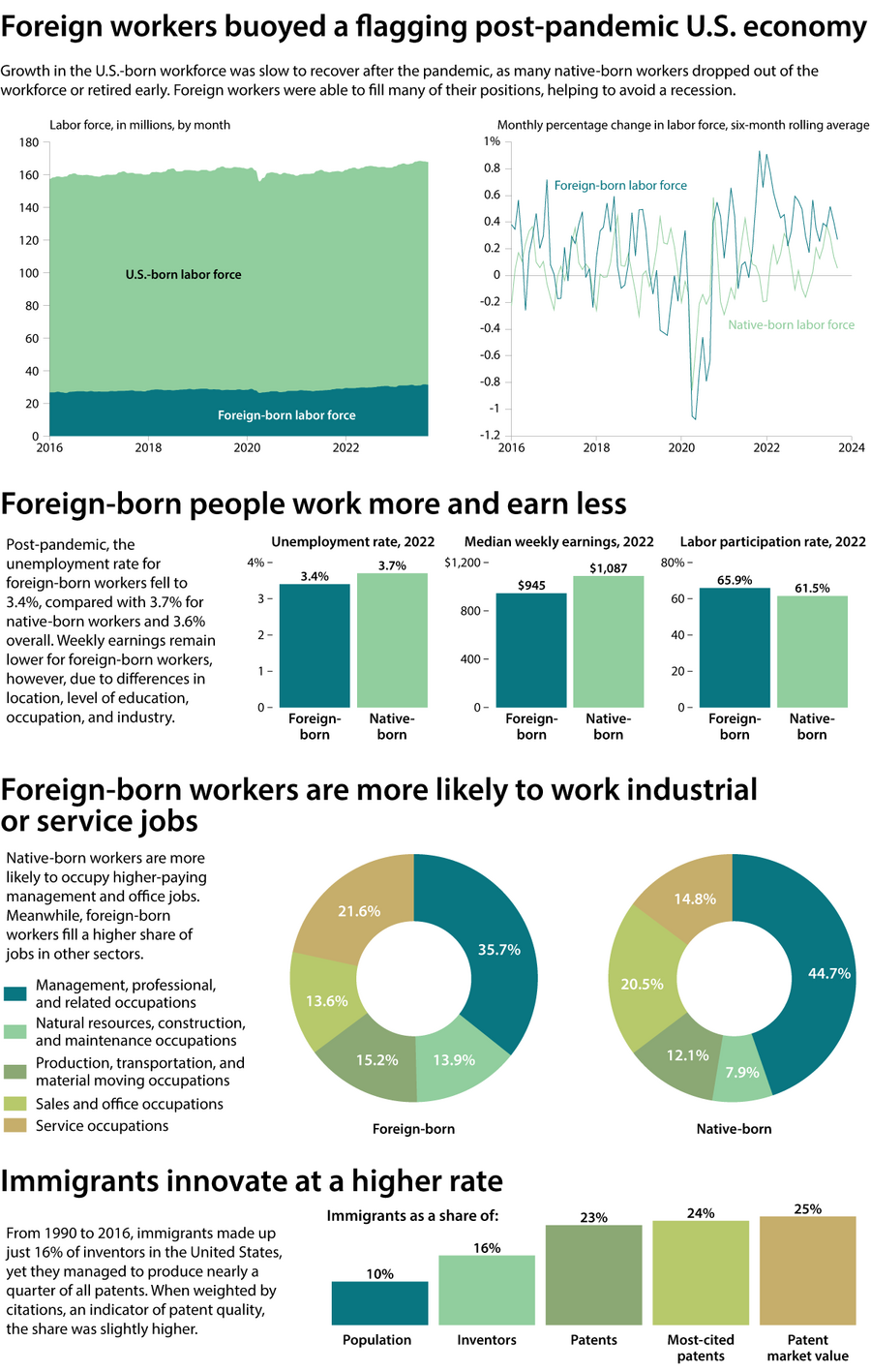

Graphic

How do immigrants affect US economy? The answer might surprise you.

Today’s news briefs

• Abortion ban reinstated: The Arizona Supreme Court said the state can enforce its long-dormant law criminalizing almost all abortions. The 1864 law allows abortions only if a mother’s life is in danger.

• Climate decision: Europe’s highest human rights court ruled countries must better protect their people from the consequences of climate change. This was the first time an international court ruled on climate change – and the first decision confirming that countries have an obligation to protect.

• Cease-fire proposal: Hamas said an Israeli proposal on a cease-fire in the war in Gaza met none of the demands of Palestinian militant factions, but it would study the offer further. The proposal was delivered by Egyptian and Qatari mediators at talks in Cairo. Israeli forces stepped up bombardments in central and southern Gaza.

• Debt cancellation: President Joe Biden announced plans to ease student debt that would benefit at least 23 million Americans. The plans include canceling up to $20,000 of accrued and capitalized interest for borrowers, regardless of income.

• Washington visit: Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio begins a state visit to the United States amid shared concerns about Chinese military action in the Pacific and public differences over a Japanese company’s plan to buy U.S. Steel. Mr. Kishida and his wife, Yuko, will stop by the White House ahead of the official April 10 visit and formal state dinner as President Joe Biden celebrates a decadeslong ally he sees as the cornerstone of his Indo-Pacific policy.

( 5 min. read )

An uptick in brazenly pro-government Bollywood movies highlights the close relationship between India’s ruling party and mainstream media – as well as the risks of blurring the lines between politics, news, and entertainment.

Essay

( 4 min. read )

Our reporter Simon Montlake, like many parents, wanted his son to experience the wonder of a total solar eclipse. As so often happens with parenting, the one left most in awe by the celestial event was not the fifth grader.

Difference-maker

( 5 min. read )

After a disaster, the best of humanity surfaces, something that was clearly seen after the devastating earthquakes in Turkey a year ago. But some have met the challenge with a special determination.

( 4 min. read )

April is National Poetry Month in the United States. Our poetry reviewer talks with Natasha Trethewey, former U.S. poet laureate, about “The House of Being,” and the memories that propel her writing.

The Monitor's View

( 2 min. read )

On April 8, or just shy of 79 years after Nazi forces surrendered in World War II, Germany began its first permanent stationing of combat troops outside its borders. The first of 4,800 German soldiers arrived in Lithuania – which borders Russia – to set up a military base. They were warmly welcomed by the Baltic nation as part of NATO’s new Forward Presence strategy against further Russian aggression in Europe.

The deployment is a historic “lighthouse project” for Germany after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, said Defense Minister Boris Pistorius. It is part of a “turning point” for Germany in improving its military and becoming a protector of European security, according to German Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

“Given Germany’s complex historical legacy and the state of its armed forces, the German commitment is astounding,” Māris Andžāns, a professor at Rīga Stradiņš University in Latvia, wrote for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

The German forces in Lithuania will complement American troops in Poland, British soldiers in Estonia, and Canadian soldiers in Latvia. Those Eastern Europe countries are considered among the most vulnerable if Russian President Vladimir Putin makes good on a promise to re-create the Soviet empire that fell in 1991. Russia has lately begun to increase its arms production by more than 60%.

Germany’s first temporary deployment of troops – in defense of Bosnia-Herzegovina – came in 1996, or more than a half-century after World War II. But such milestones did little to sway German opinion from a deep postwar pacifism. In 2011, as Russia began to flex its military might, a Polish foreign minister declared that he feared “German power less than German inaction.”

Now the Russian invasion has forced many Germans to “recognise that it may sometimes be necessary to defend territory, values and principles,” wrote Katja Hoyer, a German British historian, in the Financial Times.

Germany’s longtime reluctance to be a military leader has actually earned it a measure of trust within the 32-member NATO. “To some people, we now seem like a sometimes slow, but ultimately always helpful and, above all, reliable friend,” wrote commentator Matthias Koch in the German daily newspaper Frankfurter Rundschau. From the welcome given to German soldiers by Lithuanians on Monday, he may be right.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 4 min. read )

Each of us is divinely empowered to think and act with integrity and brotherly love.

Viewfinder

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, security writer Anna Mulrine Grobe will look at the issue of closer cooperation between U.S. and Japanese militaries, as Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio comes to Washington for a state visit.