The word “unprecedented” gets tossed around a lot. But the Supreme Court is suddenly finding itself asked to decide cases with no legal precedent to fall back on. And the rulings are likely to affect the 2024 election.

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

How much do you care about Pakistan’s latest elections?

Put another way: How much do you care about the power of human agency to support a system that at least strives to add stability in a wobbly world?

Thought so.

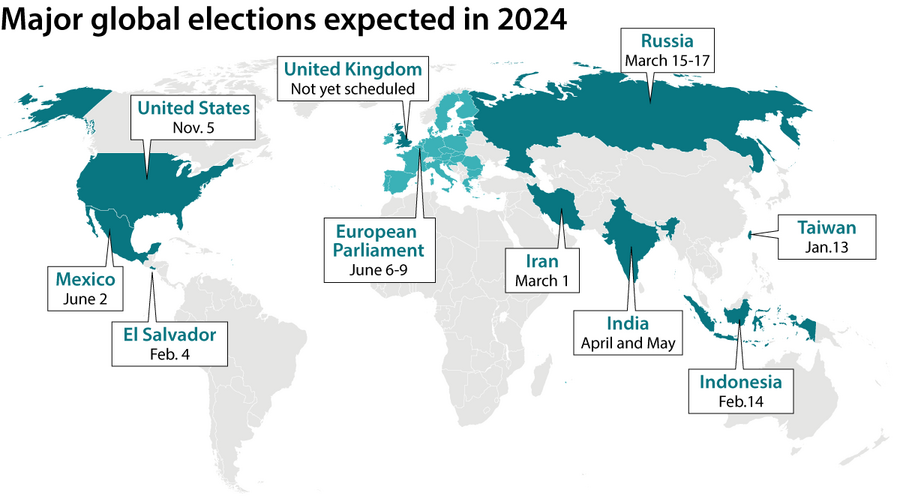

As Ned Temko notes today, a couple of billion people worldwide may go to the polls in 2024. (Hasan Ali reports on one party’s ballot barrier woes in Pakistan, in a bonus read.)

It’s democracy by degrees. Voters will encounter processes that sit on a spectrum from free and fair to outright sham. They may need to navigate artificial intelligence hazards or foreign (or domestic) interference. They may find disappointment or joy, disillusionment or inspiration.

All will be reaching for an enduring ideal.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Today’s stories

And why we wrote them

( 5 min. read )

Today’s news briefs

• Donald Trump fraud trial: The civil trial is back in session in New York. Mr. Trump seized an opportunity to speak in court at the conclusion of the trial before the judge cut him off.

• Israel genocide hearing: South Africa is accusing Israel of committing genocide in Gaza. A two-day trial begins at the United Nations’ top court in The Hague, Netherlands.

• Legendary coaches leave: Bill Belichick is leaving the National Football League’s New England Patriots, while Nick Saban is retiring as head coach of the University of Alabama football program.

• Renewable energy grows: The amount of renewable energy installed around the world last year grew at its fastest rate in the past 25 years.

( 4 min. read )

What happens when an electorate primed for fraud encounters an arcane election format with a history of hiccups? Iowa Republicans say Monday’s caucuses will be open and transparent. But any irregularities could cause big problems.

Patterns

( 4 min. read )

In “the year of the election,” around 2 billion voters worldwide will go to the polls. But different countries use elections for very different purposes.

( 5 min. read )

Amid patchy health care in many African states, sometimes one determined individual can make all the difference.

Essay

( 3 min. read )

Seeing, and experiencing, the world through a child’s eyes interrupts the monotony of grown-up life and infuses even the mundane with wonder and exuberance.

The Monitor's View

( 3 min. read )

During the nearly two years since Russia’s invasion, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has frequently used one notable word in public comments: despair. He cites it not to consent to it but to, as he says, “not allow” it. With the war currently at a stalemate, he has been battling despair among Ukrainians more than ever.

Yet not in ways easily seen.

The most obvious way is by winning more aid from Western capitals to match Russia’s military might. He has fought official corruption and kept the economy going. Lately, he has boosted troop morale by handing out more medals for combat heroism.

During a visit to the front line in December to hand out medals, he said he found “no despair and no weakness” among the soldiers. A few weeks earlier, he visited a memorial wall to fallen soldiers, saying it was a “wall that fear, despondency, despair, discord, or the thought of giving up won’t break through.”

“We are strong. We are the wall. We stand,” he said.

A year ago, during a visit to Britain in which he was presented with a special-edition Book of Psalms translated into Ukrainian, Mr. Zelenskyy quoted from Chapter 3: “But You, O Lord, are a shield about me, my glory and He Who raises up my head. With my voice, I call to the Lord, and He answered me from His holy mount to eternity. I will not fear ten thousands of people, who have set themselves against me all around.”

The Jewish president says the Psalms tell of people praying often for help from God. “We never know whether our prayer has come close to perfection, and whether the Lord heard it,” he said. “That’s why in harsh times – when we lose loved-ones; when people lose children, ... when a criminal war is conducted against your people; – faith may stagger. It happens that people think that God doesn’t hear and will not hear prayer. And it is important for us, as leaders of nations, to resist despair.”

In the first 15 months after the invasion, demand for Bibles rose fivefold in Ukraine, according to the Ukrainian Bible Society. Online engagement with the Bible also rose dramatically, according to YouVersion, creators of the popular Bible app and Bible.com.

In the year after the war began, the most popular search terms in Ukrainian were “war,” “fear,” and “anxiety,” according to YouVersion. As the war went on, those words were replaced by searches for “love.”

Perhaps that shift can be explained by YouVersion’s finding that the most popular Bible verse among Ukrainians in 2022 was Isaiah 41:10: “So do not fear, for I am with you; do not be dismayed, for I am your God. I will strengthen you and help you; I will uphold you with my righteous right hand.”

Among the top 10 favorite Bible verses among Ukrainians, “curiously absent are verses on evil, anger, and grief,” Valentin Siniy, president of Tavriski Christian Institute in Kherson, told Christianity Today.

Along with President Zelenskyy, Ukraine’s clergy have also been on the front lines, battling despair. One is Mykola Berezyk, a priest with the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

“The war showed us that it is not enough to feed, equip, and arm soldiers,” he told Agence France Presse. “They also need spiritual support.”

Mr. Zelenskyy went further in that idea during his Christmas message last month: “In troubled times, as we defend our land and our souls, we are making our way to freedom. The way to gaining comprehensive independence, including spiritual one.”

His words were one more way Ukraine plans a triumph over despair as much as a victory against an invasion.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

( 3 min. read )

Instead of blaming ourselves or others for mistakes, we can accomplish more by turning to God for forgiveness and for the lessons that enable us to go higher in our spiritual understanding.

Viewfinder

Palestinian children play during the Eid al-Adha holiday, in Gaza City, June 6, 2025.

A look ahead

Wondering what’s going on Ecuador, where gunmen stormed a TV station on Tuesday? The South American nation used to be a regional bastion of safety and stability. Today, Whitney Eulich explains what has happened – and what might happen next.

Tomorrow, watch for the next installment of our “Why We Wrote This” podcast. Middle East Editor Ken Kaplan describes how he and his team approach a very fluid war story with humanity at its core.