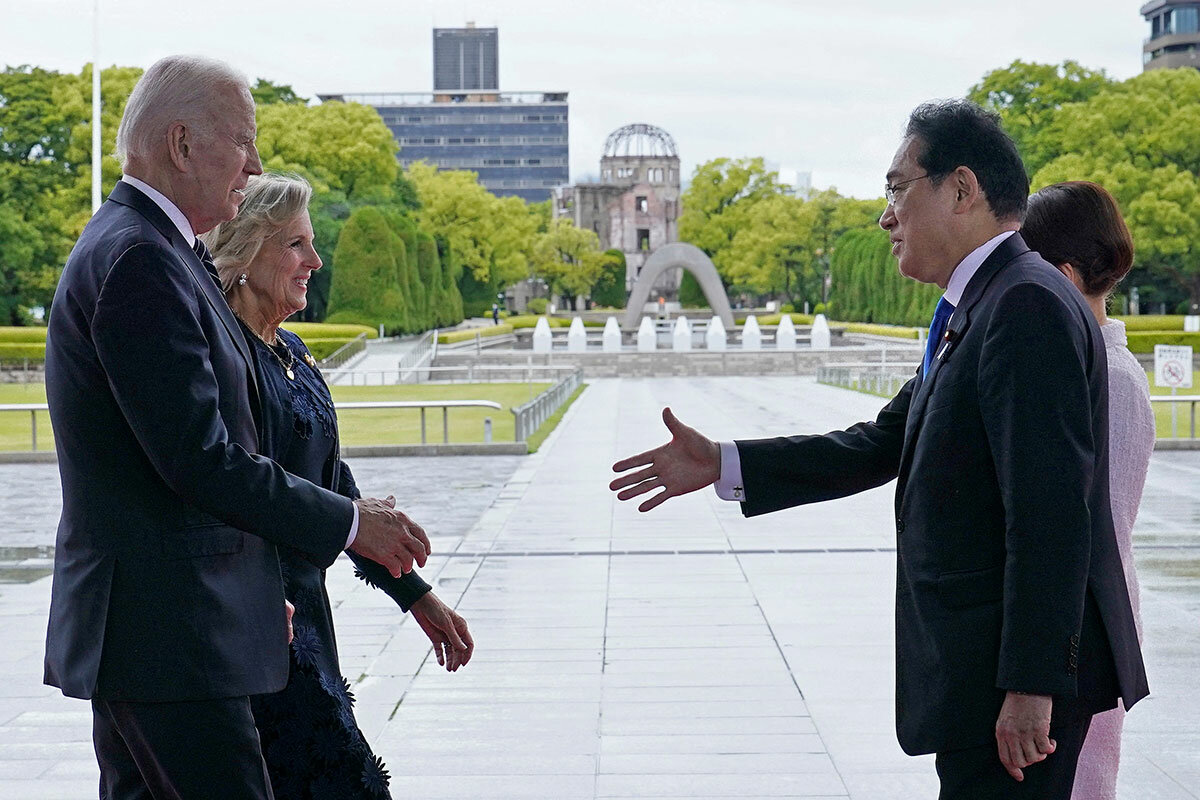

In Japan, President Joe Biden is pursuing two pillars of his foreign policy: revitalizing U.S. alliances and demonstrating democracy’s virtues as an effective governing system. Hanging over both is the debt ceiling crisis he left behind in Washington.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Linda Feldmann

Linda Feldmann

Salman Rushdie’s surprise appearance at last night’s PEN America Literary Gala – a celebration of free expression – ended a week of controversy on a high note.

It was the author’s first public appearance since he was attacked and gravely wounded last August at a literary festival in western New York.

“It’s nice to be back,” said Mr. Rushdie, who has faced death threats since the 1988 publication of his novel “The Satanic Verses,” deemed by Iran’s ayatollahs to be blasphemous toward Islam.

A clash over free speech had earlier marred PEN America’s World Voices Festival, when two Ukrainian authors threatened not to appear after learning that two Russian writers were participating in a different panel. The Russians oppose President Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine and had left their country shortly after last year’s invasion, but the Ukrainians – both active-duty soldiers – stood firm. PEN canceled the panel that included Russians.

Acclaimed Russian émigré journalist Masha Gessen quit as vice president of the PEN America board over the episode. Suzanne Nossel, the organization’s CEO, called it “a no-win situation.”

To Americans who care deeply about Ukraine while also seeking to defend Russians who have nothing to do with the war or outright oppose it, the PEN America situation is exasperating.

“The relentless zero-sum approach is just awful,” says an analyst with long experience in the post-Soviet world, speaking not for attribution. “Don’t these folks realize they are on the same side? Literally no one involved in this whole dispute supports Putin or his war, so what are they fighting about?”

The sensitivities are understandable. Russia’s invasion isn’t just territorial; it’s also cultural. Many Ukrainians now have a deep aversion to all things Russian – language, literature, performing arts. Anti-Russian sentiment has also gripped the West, leading to the cancellation of performances by Russian artists.

The Ukrainian writer-soldiers said that they faced legal and ethical restrictions that prevented their participation, and that they weren’t “boycotting.” But the end result was the same: a curtailing of speech by PEN America, ironic for an organization founded to defend free expression.

For Mr. Rushdie, recipient of an award for courage, the gala was an opportunity to stand up to the tyranny of his foes. “Terror must not terrorize us. Violence must not deter us,” he said. “The struggle goes on.”

Ukrainians and anti-war Russians can also take heart in his message.