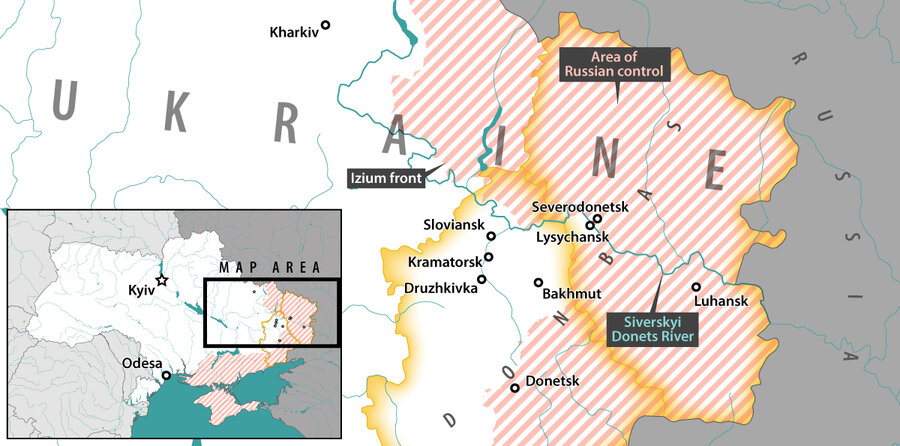

A war of attrition, by definition, tests resilience. Yet even as Ukrainian fighters bow to Russian artillery in the east, our reporter finds a dogged hope that arriving Western weapons will help them turn the tide.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

David Clark Scott

David Clark Scott

Cooperation sometimes occurs under unusual conditions. Consider the latest research on neodymium.

It gets a little geeky, but stay with me. This chemical element is used in magnets. Normally, if magnetic materials are cooled, the spin of their atoms “freeze” – lock into place in a static pattern, showing what researchers call “cooperative behavior.”

But for the first time, physicists have found that atoms of neodymium “freeze” not when they’re cooled but when they’re heated. “It’s quite counterintuitive, like water that becomes an ice cube when it’s heated up,” said Dr. Alexander Khajetoorians at Radboud University in the Netherlands.

The behavior of neodymium got me wondering about other examples of counterintuitive cooperation.

This past year, Israel was governed by a coalition of ultranationalist right-wingers, pro-peace leftists, centrists, and, for the first time, an Arab Israeli political faction. That government recently dissolved, but it remains a remarkable example of unlikely political bedfellows.

Another case of odd allies illustrates the proverb, “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Saudi Arabia has never recognized Israel. Yet the two nations have unofficially engaged in security cooperation against a mutual adversary, Iran. There are reports that President Joe Biden may help pave the way for closer official ties between Jerusalem and Riyadh next week.

American school curriculums have become heated battlegrounds over teaching the history of racism. But in one Tennessee community, we find Black, white, and Hispanic moms are united in modeling respect and civility.

In a competitive, polarized world, the concept of working together might seem outdated. But the evidence suggests that in nature – ranging from atomic motion to geopolitics – cooperation keeps finding new ways to flourish.