A generation after the Good Friday Agreement ended one of the world’s longest sectarian conflicts, Northern Ireland’s carefully balanced calm is showing signs of strain.

A ballot victory early this month by the political party Sinn Féin marked the first time in a hundred years that those who seek to unite the province, formally part of Britain, with the rest of Ireland are poised to lead. Since then, however, the ousted Democratic Unionist Party has blocked the formation of a new government.

Then earlier this week, a bill in the British Parliament offering amnesty for perpetrators of violence during three decades of “the Troubles” caused an outcry. Northern Ireland has never had a systemic vetting of past atrocities.

At the same time, Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union has exacerbated economic fears for the province. (Ireland remains in the EU.) Political division over Brexit was partly to blame last year for the worst sectarian riots in a generation. Catholic and Protestant communities remain divided by segregated housing and an estimated 116 “peace walls.”

Those fault lines, however, mask social trends that show a society forging deeper bonds of unity. One measure is a groundswell of public support for integrated schools that teach children about the shared history, language, and values of their rival religious communities.

For the main political parties, “keeping schools religiously segregated means keeping their own communities, identities, and vote base intact,” Abby Wallace, a university student in Belfast, wrote in The Guardian recently. “But these divisions are already broken and outdated, and don’t represent young people in Northern Ireland today. Every year, more young people are ditching sectarian labels, which no longer reflect the subtleties of how we define ourselves. Those engaging in violence are a minority.”

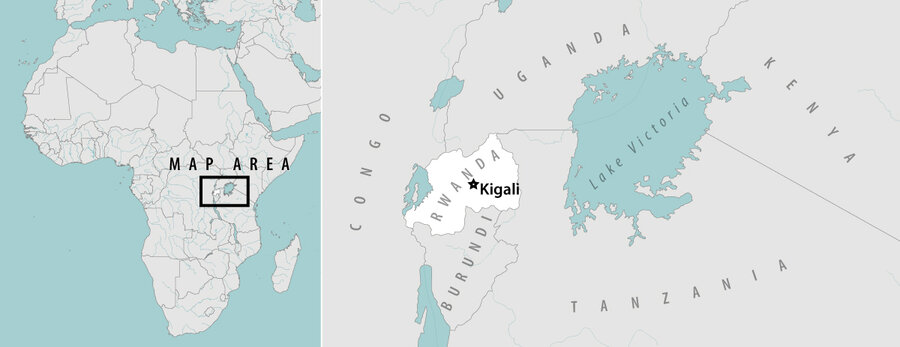

Integrated schooling has found either currency or curiosity in a number of societies emerging from conflict, such as Rwanda, South Africa, and Israel. In Northern Ireland, education was segregated on the basis of religion when the province was formally incorporated into Britain in 1921. The first integrated school was started in 1980. But the idea – and the development of curricula based on “principles of inclusion, respect, trust, and cross-cultural critique of alternative world views,” as a study noted last month – has gained momentum more recently.

Parents are driving the demand. Northern Ireland now has just 68 integrated schools. They reach just 7% of youth and represent a small fraction among more than a thousand schools that are predominantly or exclusively Catholic or Protestant. But they reflect a broader view of a society outgrowing past divisions. A survey by the polling firm LucidTalk last August found that 79% of adults believe that all schools should “aim to have a religious and cultural mix of its pupils, teachers, and governors.”

That support marks a dividend of the peace accord. Adults who grew up in an era of conflict and segregation now mix at work. That exposure has helped them discover common humanity across sectarian boundaries and recognize the value of integration in their children’s education. That insight is driving a shift in policy. In March the Northern Ireland Assembly passed a bill requiring the government to promote integration in all public schools.

“It’s not just about the pupils,” Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis noted recently. “It’s also about the parents. The more time we spent together, the more time you realize the cliché is true – that we always have far more in common than ever divides us.”

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield