Both parties agree only Congress can fix the strained U.S. immigration system. But with Trump-era deportation tool Title 42 set to end next month amid a record influx, there is little agreement about potential solutions.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Peter Grier

Peter Grier

Big Henry is a beagle who thinks he’s something else. A Labrador, maybe.

First of all, he’s big. Henry – our latest foster dog – is twice the size of other beagles. He can’t howl like a beagle. His barks sound like strangled yips.

And he doesn’t act like a beagle. He hip-checks you when he wants a pat, like big dogs do. He wriggles like a snake when he’s happy, like a Pekingese. He’s friendlier to dogs he doesn’t know than are many hounds.

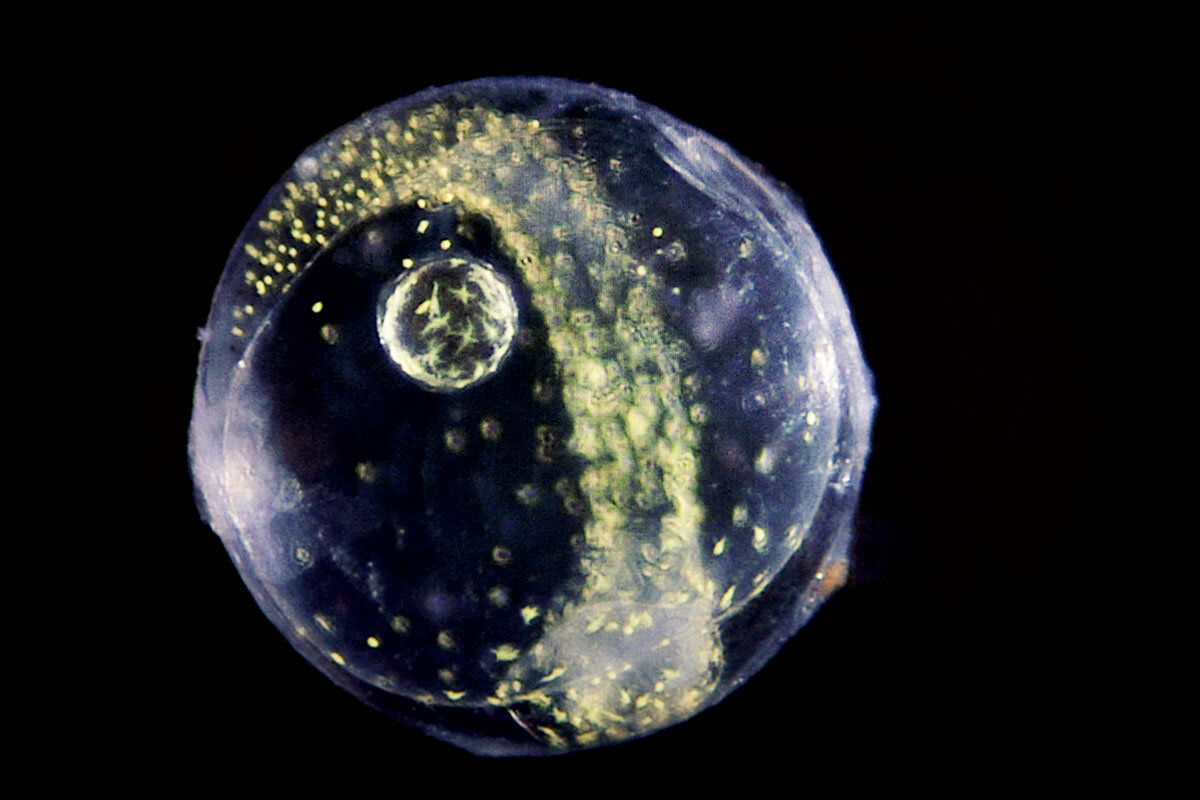

Maybe he’s a mixed breed. But maybe we’ve also stereotyped him. A new study out this week from scientists who have long studied dog genetics finds that breed heritage has far less influence on canine personality than we think.

Chihuahuas perhaps aren’t inherently nervous. Golden retrievers may not all be mellow. Pit bulls might not be aggressive, unless taught to be.

“Dog breed is generally a poor predictor of individual behavior and should not be used to inform decisions relating to selection of a pet dog,” concluded the study, published Thursday in Science.

The research combined DNA sequencing of 2,000 dogs – purebred and mixed breed – and self-reported surveys from thousands of dog owners.

The results showed some general traits are inheritable, such as responsiveness to commands. But that inheritability didn’t distinguish breeds from one another. Breeds accounted for only 9% of behavior variation in individual dogs, according to the study.

Maybe that shouldn’t be surprising, given that breeds emerged only about 160 years ago – a blink in time compared with the overall 10,000-year history of dog species.

However, Henry is a true beagle in one respect. His nose. He sniffs everything. A walk around the block can take an hour.