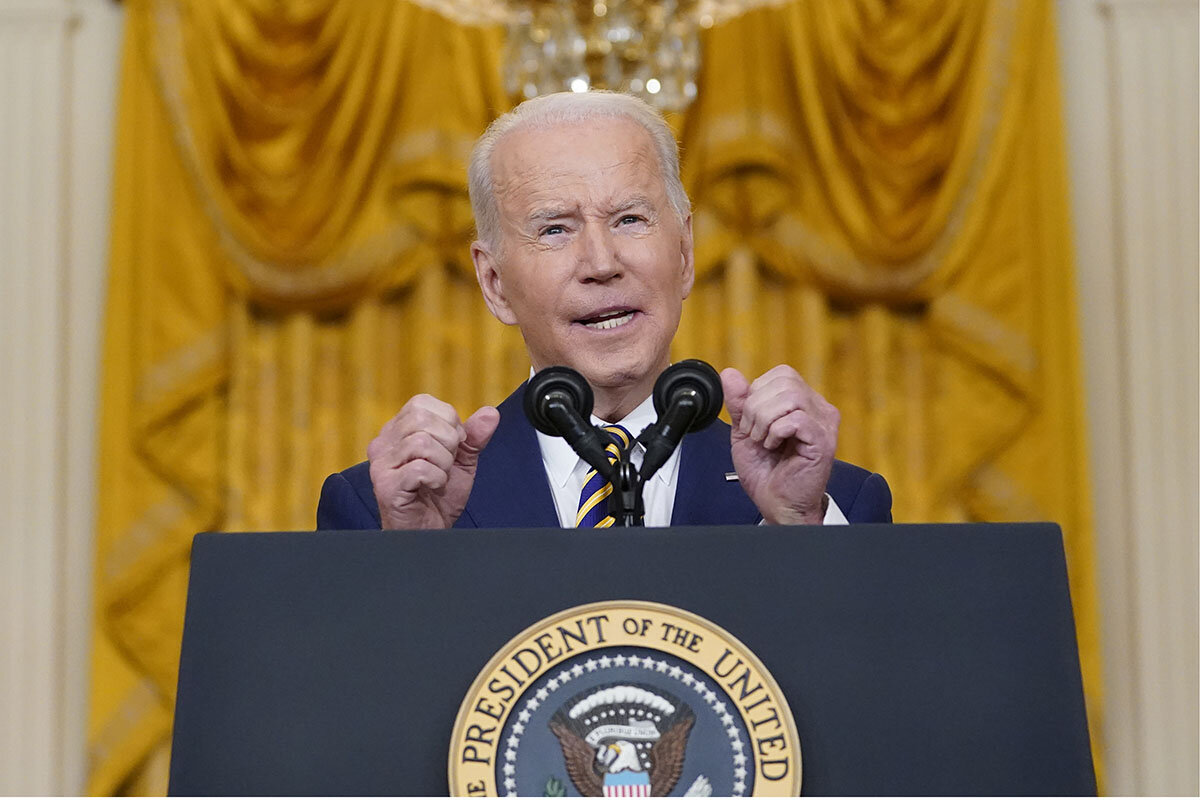

The American presidency often involves major on-the-job training, as Joe Biden is learning. Despite historic challenges and a polarized electorate, experts say it’s not too late for the president to turn things around.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

For generations, the Mideast has been synonymous with protracted sectarian strife. But quietly, things are changing. The hard lines that have characterized the region are showing signs of softening.

A week ago, our Taylor Luck looked at the Gulf’s evolving perceptions of one enemy: Iran. Today, our editorial examines Arab states’ shifting stance on Afghanistan. But most interesting, in many ways, is a new relationship with Israel. Or perhaps an old one, Taylor says.

“This real political alignment between Arab states and Israel has unlocked a secret past: Jews have long been part of the Arab world and are an integral part of its history,” he says.

This past was erased by the Arab nationalism of the 1960s and ’70s. But the pulling back of American influence in the region has forced Arab countries to rethink their alliances. One revelation is that Israel can be a valuable strategic partner.

This realignment “is reviving a history of ... the coexistence and co-dependence of Jews and Muslims, the importance of Arab Jews to the advancement of the Arab world,” Taylor says. Jewish neighborhoods in the Gulf and Cairo are being put back on maps, historic synagogues are no longer being hidden, and landmarks of Jewish artisans, intellectuals, and writers are being recognized from Tunisia to Bahrain.

There are sure to be political bumps ahead, but the cultural shift “is likely to continue to strengthen,” Taylor says. After all, “Jews, Muslims, and Christians are natural neighbors, and form a community.”