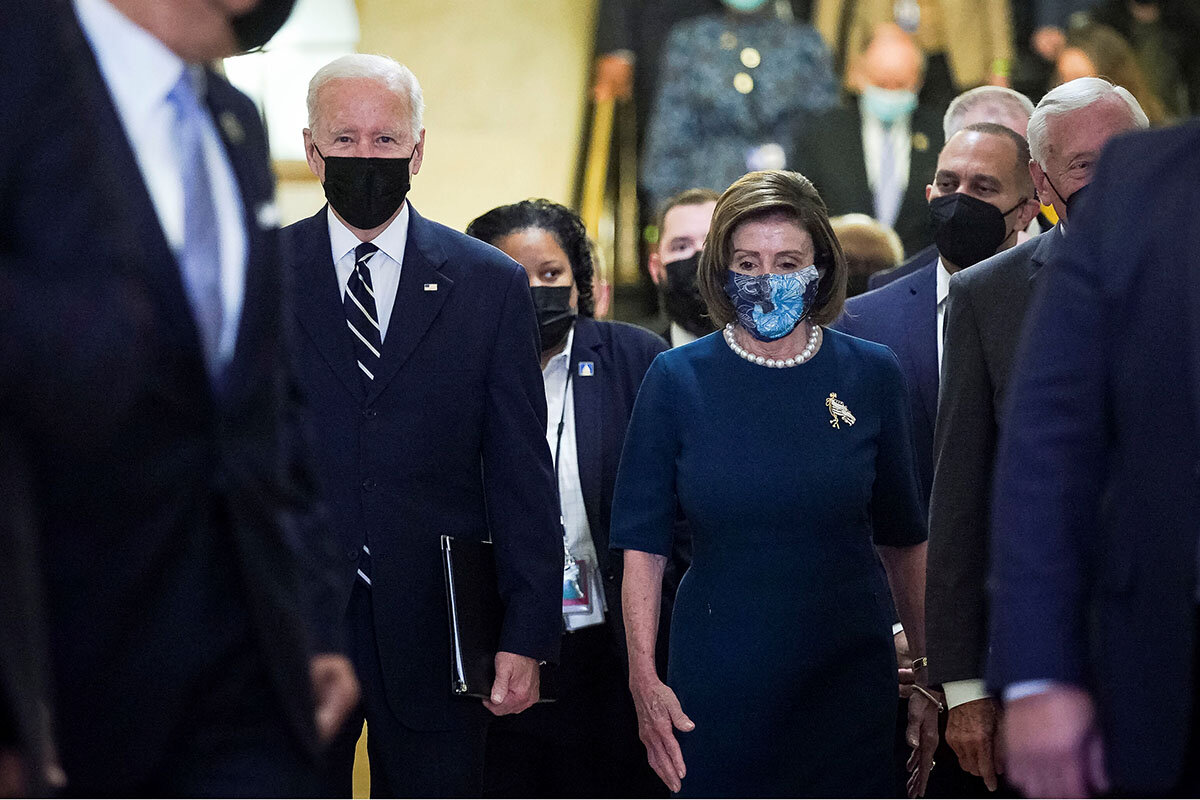

The course of Joe Biden’s presidency will likely be set in the coming days by the fate of his two signature bills.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

An important thing happened when East Londoner Barbara Grossman met her member of Parliament. She felt included. She felt connected. She felt her bonds with her own community – and the government – became stronger.

If there’s a lesson in today’s Daily, that’s it. Democracy must build connections and create a steadily larger sense of community. But that work is not easy, and perhaps too easily reversed.

Through Ms. Grossman and others, our Shafi Musaddique looks at the importance of politicians’ connections with their communities in the wake of a tragic killing. Can Britain keep that openness despite new security threats? Other stories in today’s issue point to the importance of the answer. Japanese democracy has in many ways stagnated because the rules for participation simply enforce the status quo. Sudanese women have won unprecedented freedoms during the past few years, but a new coup could snuff them out.

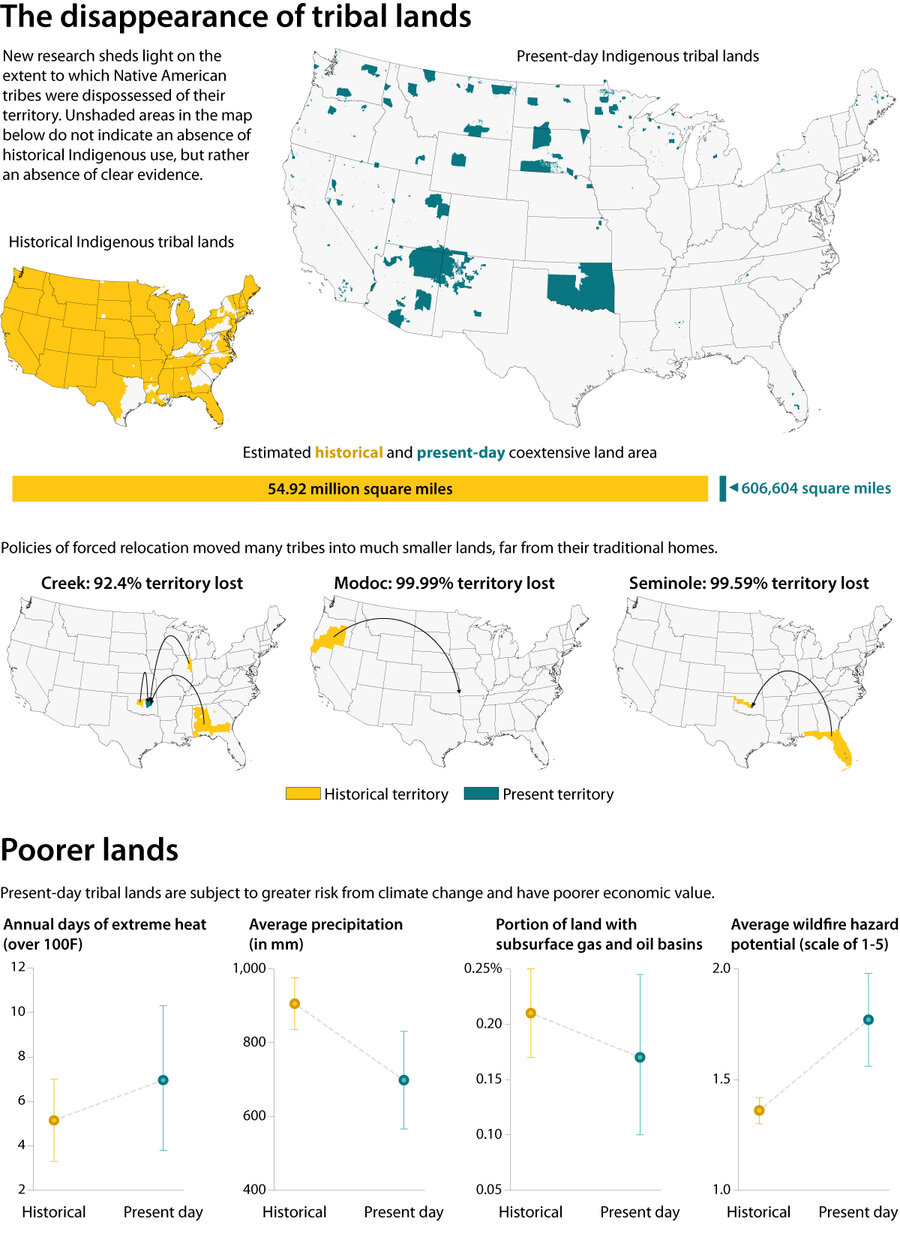

In its purest state, democracy promotes freedom and responsibility, expands our sense of community, and promises universal inclusion. Humanity is still wrestling with the enormity of those demands. Our graphic on how Indigenous communities in the United States were systematically dispossessed of their lands is proof.

But our final article about the historical discoveries of an author investigating Black lives during the 1700s and 1800s hints at the promise. Progress toward real, universal freedom and equality reveals troves of human richness. How are our democracies wrestling with that demand today? From Britain to Sudan, we offer a window into the struggle.